Altman’s latest is gentle and stunning, relying on movement to tell story

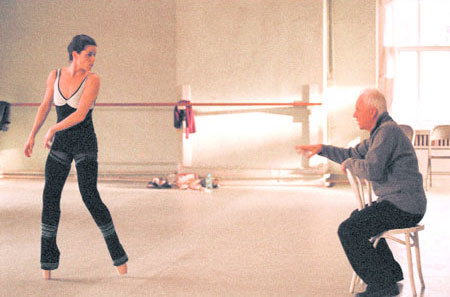

Neve Cambell as Ry and Malcom McDowell as Alberto Antonelli.

Matt Dinerstein

A lovely Christmas gift, “The Company” represents Robert Altman at his kindest and most gentle. Even when in a genial mood, as in “Cookie’s Fortune,” he’s been known to thrown in a few misanthropic touches. They’re missing entirely from his latest film. It deals with characters Altman seems to like and respect, but resembles “Kansas City,” one of his worst and nastiest films, in its structure. In both cases, thin narratives are broken up with performances: jazz there, ballet here.

The storyline of “The Company” is so simple that the press kit for the film foregoes describing the plot entirely. It’s set at Chicago’s famous Joffrey Ballet. Neve Campbell, who co-wrote the story with screenwriter Barbara Turner and trained a ballerina before appearing in “Party of Five” and “Scream,” plays Ry, a dancer who also works as a part-time waitress. Antonelli (Malcolm McDowell), who leads the troupe, clearly thinks of himself as a larger-than-life artiste, loudly urging his young dancers to avoid prettiness and, for one number, bring back the rebellious spirit of the 60s.

The cast is large, but includes many real Joffrey dancers basically playing themselves, most of them using their real names. With this crew of real ballet dancers, choreographer Robert Desrosiers mounts a bizarre performance called “Blue Snake.”

“The Company” often feels like a cinema vérité documentary about the Joffrey, although the camerawork and editing are too slick to pass for one. It’s a ballet lover’s delight. Shooting on HD video didn’t harm the film, although it’s not as visually impressive as Alexander Sokurov’s “Russian Ark,” which has become the high watermark for DV beauty. Cinematographer Andrew Dunn used multiple cameras during the performances, allowing for graceful cuts and shifts of perspective. Although the film looks slightly fuzzy, it’s no worse than a 16mm blow-up.

Altman hasn’t suddenly become a humanist. In fact, some of his crueler films showed more interest in people than does “The Company.” Through much of the film, he treats the cast more as bodies than characters. This doesn’t mean that he glamorizes everyone or glosses over their hard work––some dancers’ feet are covered with blisters and bandages. A brief glimpse of breasts isn’t eroticized or dwelled upon. Still, a sensual, fetishistic veneer pervades the whole film, down to even a cooking scene.

Without telling a conventional story, “The Company” generates plenty of drama. There are egos to be bruised, tendons to be broken. One of the film’s early performances happens at an outdoor stage in Grant Park, on Chicago’s lakefront. A sudden storm interferes with the dance. The audience huddles under large umbrellas. While the stage is covered, it’s still prey to a fierce wind. Will the rain make the stage too slick to dance on? This sequence becomes quite suspenseful.

All the same, “The Company” might have worked better as a real documentary about the Joffrey. Altman edited all the music scenes filmed for “Kansas City” into a separate film, “Jazz ‘34.” A similar departure based on “The Company” might be just as entertaining as the film.

The size of the film’s cast and the large amount of time dedicated to dance scenes ensured that the story remained minimal and fragmented. Altman apparently trusted that narrative would naturally flow if he paid attention to this set of characters long enough. Unfortunately, it really doesn’t.

Given all that the film does deliver, that’s not fatal, but it does limit the appeal of “The Company.” Ballet fans may think it’s a masterpiece, but the rest of us might wish for a more satisfying closure to the story than yet another dance scene.