Of all the great songwriters of the last century, one of the greatest, most distinctive, and — to Americans — least well-known is Charles Aznavour, who died a year ago at age 94. Astonishingly prolific, he was the writer of some 1,000 songs — with countless recordings; music poured out of him. He was born in Paris, the son of a pair of Armenian immigrants who, as members of the Resistance during World War II, hid refugees from Nazi persecution. The family was awarded the Raoul Wallenberg Award in 2017 for risking their lives in this way, and that spirit of humanity always informed Aznavour’s work.

He began performing as a child with his father who was a singer, then became an actor on stage and in the film “La Guerre des Gosses,” finally turning to nightclub work as a dancer. In 1944, he partnered with actor Pierre Roche and began writing songs, and was encouraged to sing by his mentor Edith Piaf, who hired him as her opening act. His ability to sing in numerous languages gave him the kind of international appeal sought by major venues like Carnegie Hall and the Royal Albert Hall, exacerbated by the success of records like “She,” “The Old-Fashioned Way,” “Sunday Is Not My Day,” “Après l’amour,” “Sur ma vie,” and the great, harrowing “Yesterday, When I Was Young.” That last was Mickey Mantle’s favorite, sung by the Yankee slugger’s request at his funeral. Aznavour’s music had remarkable reach, with some 180 million records sold in his lifetime.

Though not gay himself, one of this all-encompassing artist’s most beloved songs deals specifically with queerness, “Comme ils disent” (or, as it is better known, “What Makes a Man”). This 1972 work, covered by innumerable artists from Marc Almond to Aznavour’s great friend and champion Liza Minnelli, tells the story of a drag performer who lives with his mother and gets fulfillment from fooling his audience nightly about his gender, while pining hopelessly for men who prefer women and enduring a time when homosexuality remained too widely forbidden.

The rules that some of us must break

Just to keep living

I know my life is not a crime

I’m just a victim of my time

I stand defenseless

Nobody has the right to be

The judge of what is right for me

Tell me if you can

What makes a man a man.

That’s how the song ends, and, in its way, it might be the first-ever gay protest anthem. I am so looking forward to hearing it again soon, when the wonderfully gifted Jean Brassard brings his Aznavour tribute show, “I Have Lived,” to Pangea on September 23, with a run to follow in London at The Pheasantry October 11-12.

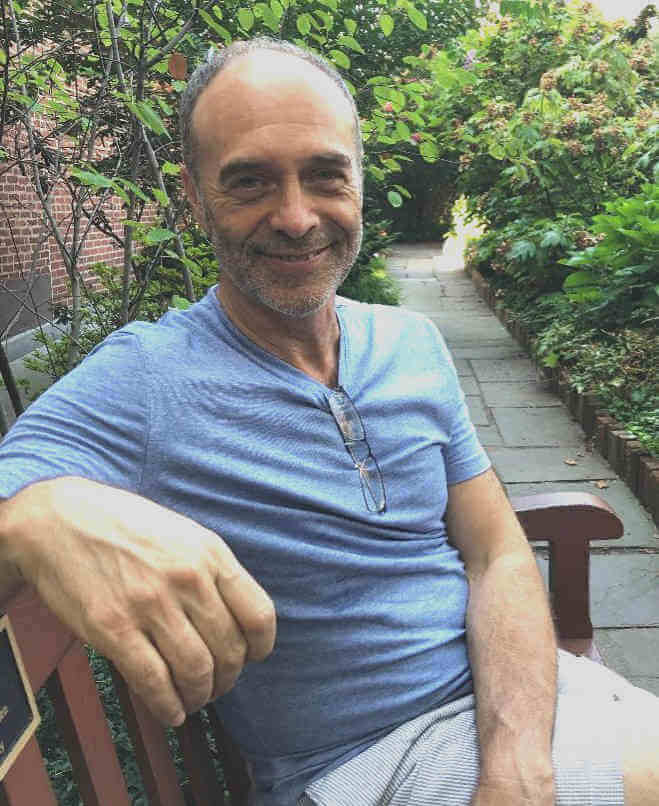

I met Brassard for an interview in the charming secret garden of the Village church St. Lukes in the Fields, and he observed, “Aznavour strikes me as a playwright, or even filmmaker, who just happened to write in short form — songs. For a performer like me, who approaches everything from an actor’s point of view, his world offers a realm of possibilities. He specialized in love, a recurrent theme, and there isn’t any aspect of it that he didn’t cover, from the very beautiful to the very ugly.”

I first met Brassard when he did his luminous salute to another French music (and film) icon, Yves Montand, and was then struck by his compelling stage presence, charming voice, and pure artistry in the way he deftly wove Montand’s music and career into memories of his own life, growing up in a close and loving family of French Canadians. He has only gotten better since, and I cannot think of a better interpreter to introduce me and so many others to the kaleidoscopic oeuvre of Aznavour.

Brassand is marvelously knowledgeable about the rich tradition of the French chanson, and other singing contemporaries of Aznavour’s, most of them new names to my ears, such as Boris Vian and Leo Ferre (“another tremendous poet, darker, critical as well as apocalyptical and at times tremendously sad”). I have always adored Charles Trenet, most known here for his indelible, mellifluous “La mer,” who came before Aznavour’s generation, but was very popular — and gay. Brassard told me that Trenet was a big influence on Aznavour, who loved him and bought his entire catalogue.

“People forget how brave and out there it was for him to do ‘Comme il disent’ at a time when being gay was far from an accepted thing. But he knew himself what it was like to be an outsider and treated with prejudice, as an Armenian and as a short, not conventionally handsome leading man type of performer… Many singers have done this song — some go really over-the-top — but I love the way Aznavour did it, very simply, all the emphasis on his face, his eyes, with just one hand framing it.”

In a 2012 interview, Aznavour said, “I was the first to write a song in France about homosexuality. I wanted to write about the specific problems my gay friends had. I could see things were different for them, that they were marginalized. I always wrote about things that others might not have written about. We don’t mind frank language in books, the theater, or cinema, but for some reason still to sing about such things is seen as odd.”

Originally, his entourage implored him not to release the song, which went to the top 10 in France. But, Aznavour continued, “I wanted to write what nobody else was writing. I’m very open, very risky, not afraid of breaking my career because of one song. I don’t let the public force me to do what they want me to do. I force them to listen to what I have done. That’s the only way to progress, and to make the public progress.”

Brassard is not a big fan of the song “Yesterday When I Was Young,” telling me that he found the lyrics hard to relate to. It basically is a rueful meditation on a life lived with total self-centeredness and entitlement, leaving its protagonist alone on a stage without a single friend or lover — Aznavour’s “Je regrette tout,” if you will. Brassard — though a marvelously versatile character a actor who works constantly (he really sparkled in J.C. Khoury’s indie farce “The Pill,” as the daunting paterfamilias) and has had the most intriguing side gig as a commentator for the WWE — has always struck me as a most un-actory, down-to-earth person, so I guess it’s small wonder that he has no affinity for this chanson of assholery, however brilliantly wrought by a master. He has also been very happily partnered for years with the eclectically talented artist DG Krueger. I suggested he sing “Yesterday…” not as any version of himself, but as any formerly designatedly “hot” Manhattan strutting stud muffin finally coming to realize that karma does in fact exist. I detected a gleam in his eye when he said, “Let me think about that.”

Sticking to things French, “Olivia” (1951), the greatest lesbian film you’ve never heard of, may have just wrapped an engagement at the Quad, but the good new is that it will soon be available on DVD from Icarus Films — after being decades out of circulation. Directed by the pioneering Jacqueline Audry (also deserving of more modern renown) and adapted from an autobiographical novel by Dorothy Bussy, it is set in an elite 19th century French girls’ boarding school, dominated by two teachers Julie (Edwige Feuillère) and Cara (Simon Simone), who compete for the deepest affections of their student body while harboring an intimate history of their own. Pupil Olivia (Marie Claire Olivia), newly arrived, finds herself torn between these two alluringly Gallic Miss Jean Brodies, but finds herself leaning toward Julie. Her teacher’s imperial reading of a passage from Racine’s “Andromaque” is what clinches her crush, while poor, ever more neurotic Cara can only offer less elevated enticements like shared bon-bons to specially invited girls in her exquisitely appointed chamber, where she languishes, nursing various psychosomatic ailments.

Audry’s triumph is creating an entire, hyper-elegant, and high-minded organic universe, where men are largely non-existent and the exaltation of the love of women for each other is merely seen as the natural way of things. What is striking is not only its shocking boldness for its time, but the fact that it is completely devoid of homophobia, with not even one of the young girls recoiling in disgust or shrieking about the perniciousness of dykes. No outsiders ever appear to oppress this happily insular Sapphic league; any oppression comes from within their ranks, born of overweening narcissism and the inevitable human thirst for power and control. The movie is lovely to look, its rich period decor and details akin to the opulent productions of Max Ophüls, with whom Audry apprenticed.

Four superb performances add to the novelistic richness. Marie Clare Olivia in the title role is initially a dewy innocent but learns the lay of the land in a trice, going after what she wants with fierce determination, while touchingly conveying the delicacy of a girl’s heart and loins being stirred for the first time.

Yvonne de Bray wonderfully opens the film as the all-service housekeeper, giving Olivia the full 411 as she drives her to the school from her train. As Cara, Simon Simone, prettily encased in the beautiful fin-de-siècle gowns (by Desvignes and Leydet), brings her full panoply of kittenish allure, that soulful, inimitable pout, caressing baby voice, and liquid grace. But it’s the great diva eminence, Edwige Feuillère (France’s first Blanche DuBois and a legendary Camille), who dominates the film, as well she should, as the school’s superstar player. You can absolutely understand why her charges worship her so, this rara avis who stalks her turf with such magnificent authority, gotten up like a queen and flinging little compliments and sharp observations at them with that legendary voice, which they eagerly grab like so many flung diamonds. The actress navigates her way through the tricky but ever-present elements of not only lesbianism but also forbidden intergenerational love with a kind of miraculous, seeming nonchalance that is, nonetheless, ever wary and careful.

I HAVE LIVED: JEAN BRASSARD SALUTES AZNAVOUR | Pangea, 178 Second Ave, btwn. E. 11th & E. 12th Sts. | Sep. 23 at 7 p.m. | $20 at pangeanyc.com