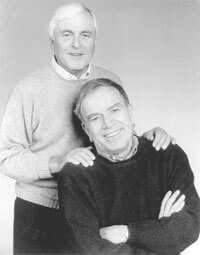

The modern musical stage’s dynamic duo to be feted at Carnegie

If they had done nothing more than write one song, the one that begins: “What use is sitting alone in your room—” they would have gained a memorable place in American cultural memory. If they had done nothing more than write the music and lyrics of that and every other number in the shattering show that surrounds that song—especially “Wilkomen”—they would have earned their place among the gods.

“Zorba.” “Chicago.” “The Act.” “The Rink.” “Woman of the Year.” “New York, New York.” “Steel Pier.”

Just for a few. And oh yes, “Kiss of the Spider Woman.”

This coming Monday evening, November 3, in Carnegie Hall, John Kander and Fred Ebb are to receive an all-star tribute for their life work in a gala program featuring Liza Minnelli, Maureen McGovern, Lanie Kazan, Judy Collins, Karen Mason, and many others, backed by the 90-piece New York Pops under the baton of Skitch Henderson. The evening is a benefit for Lauri Strauss Leukemia Foundation. The Foundation’s Herb Strauss has been a friend of John Kander’s for 50 years.

Where did it all begin for Kander & Ebb? Why don’t we ask them?

The doormat in front of Fred Ebb’s apartment on Central Park West proclaims: “SPIKE LIVES HERE.” Lyricist Ebb opened the door at 10:30 a.m. He was cradling a small dachshund in his arms. Come in. Meet Spike.

Composer Kander, who lives not far off on the Upper West Side, arrives a bit out of breath a few minutes later. “My house is all torn up,” he said by way of apology.

Kander is 76, and in the pink. Ebb is 70, and speaks somewhat slowly.

Neither man wanted to know any details about the upcoming event at Carnegie Hall. They sat at Ebb’s kitchen table—you should see that kitchen—and start talking. Arturo, who works for Ebb, brings water and coffee for anyone who wants it.

“In 1962,” said John Kander, “we were both signed to the same music publisher, Tom Valando, after each of us had done shows with other people that had opened and closed. My show, at the Billy Rose on 41st Street, was ‘A Family Affair,’ which I’d written with James and William Goldman, whom I’d known since we were kids and had all gone to camp together and then, later, lived together with in New York for a lot of years. The show? About a middle-class Jewish family having a wedding.”

Which you all knew very well?

“Yes, we certainly did.”

Ebb’s turn:

“My show, at the Phoenix [Second Avenue and 11th Street], was a very serious musical called ‘Morning Sun,’ with book and lyrics by Paul Klein based on a short story by Mary Deasy that had won the O’Henry Memorial Award. The producers were Houghton and Hambleton––”

“Norris Houhton and T. Edward Hambleton,” said Kander. “I never knew what the T stood for. I still don’t.”

“It was a very substantial failure,” said Ebb.

“Was your failure more substantial than my failure?” asked Kander. “Anyway, Tommy Va-lando signed us, separately, and thought we’d like each other and arranged for us to meet. We met, shook hands, talked, and have been doing it ever since. We didn’t start on a project. We just started writing songs—,”

“And very soon after that,” said Ebb, “we had a hit song, ‘My Coloring Book.’”

Kander: “I’d written some special material for Kaye Ballard, and we wanted Kaye to sing it on the ‘Perry Como Show,’ but they wouldn’t let her sing it because they looked on her as a comedienne, not a singer. So a girl named Sandy Stewart sang it.”

Ebb: “And to our surprise and delight, we got thousands of letters, after which there were like ten recordings of that song, the big ones being by Kitty Kallen and by Streisand.”

Kander: “At the same time we did start a project, ‘Golden Gate,’ which Hal Prince got interested in. Hal had come in and directed ‘A Family Affair’ after the previous director had left, and had almost made it work.

“Now Hal asked us to write songs for ‘Flora, the Red Menace’ [a satire of 1920s Bohemian radicalism], which George Abbott was going to direct. That’s when Liza Minnelli appeared in our lives.”

Ebb: “She was appearing in ‘Carnival,’ out on the Island somewhere. A mutual friend brought her in. We played some of our songs for ‘Flora,’ and she fell in love with them and asked if she could audition for the show. Mr. Abbott didn’t care for her. A lot of other people auditioned, and were no good, and then Mr. Abbott did care for her. She got the part, we both fell in love with her, and she’s been in our lives ever since”––not least with a film called “Cabaret.”

May we talk, gentlemen, about the genesis of “Cabaret,” the Broadway musical?

Kander: “You never know where these things are coming from. Hal Prince, when he was producing ‘Flora,’ said: ‘Whatever happens with ‘Flora,’ the day after it opens we’ll meet at my apartment to discuss our next project, a musical version of ‘I Am a Camera.’ [the John Van Druten play drawn from the ‘Berlin Stories’ of Christopher Isherwood].”

Ebb: “Which, frankly, I thought was a bad idea. I didn’t know where the love interest was. It was kind of a knee-jerk reaction to that material. Until I got talking with Joe Masteroff [who was to write the book of the show] in weekly meetings at Hal’s. Also I was coming off a flop. Two flops. ‘Morning Sun’ and ‘Flora, the Red Menace.’ I was insecure. Very nervous. [Long pause.] I was scared, really.”

Kander: “It isn’t every producer who would say, as Hal did, success or flop, let’s go to work again the next day. Nobody would say that today. Times change.

“I don’t know, I just didn’t react the same way to Hal’s idea [as Ebb had]. I found the project exciting. That bizarre, out-of-the-ordinary German popular music of the 1920s. So exciting and alive, really something I’d fallen in love with,” said Ebb, America’s answer to Kurt Weill. “When I was in high school in Kansas City, I used to have a recording of Dietrich singing ‘Johnny’ [‘Su-rabaya Johnny’] that I’d play at night on the phonograph before going to bed.”

Kander & Ebb’s many fans include Karen Ziemba, encountered not long ago between acts at the current revival of “Cabaret.” She had glorified their work a dozen years earlier in the sparkling Off-Broadway musical “And the World Goes Round.” Between the acts of Cabaret at Studio 54, she declared, among other things: “Fred Ebb is a great American poet.”

“Well, she’s prejudiced,” Ebb muttered at his kitchen table.

Even more daring than “Cabaret” in some ways was the Broadway musical “Kiss of the Spider Woman,” crafted by Kander, Ebb, Prince, and Terrence McNally from the Hector Babenco movie based on the novel by Manuel Puig. The musical was brought to life on stage by the glorious presence of Brent Carver and Chita Rivera.

Where “Cabaret” had a young man and a young woman separately bedding the same man in Hitler’s Germany, “Spider Woman” had a gay and a straight cellmate falling in love in a Latin American torture prison.

Where had that project sprung from?

Kander waved a hand toward Ebb—his 40-year partner in creativity but never in domesticity, much less romance. (Kander has lived for 26 years with one man, a choreographer and teacher. Ebb at present lives alone.)

“Spider Woman came from Fred,” Kander said. “He said the title to me one day. Just once. I said: ‘Yes.’ That was it. No further conversation. We said the title to Hal Prince. He said: ‘Yes.’ And everybody else said: ‘A terrible idea.’”

“Except for Terrence McNally,” said Ebb, “with whom we’d done ‘The Rink.’”

John Kander was born in Kansas City, Missouri, March 18, 1927. His father was––

“Rich,” Ebb interjected.

“Why do you always say that?” Kander asked. “My parents were Harry and Bernice Aaron Kander. My father was in the poultry business, working for my grandfather. There was a lot of music in my family. My father had a big booming baritone voice, and my grandmother and my aunt and my brother all played piano. Everybody in the house had music except my mother, who was tone deaf, but she did have rhythm. I played piano from age four.”

Kander went to college at Oberlin because it had a strong music department, a strong liberal-arts heritage, “and also because it was a non-fraternity school. My brother Edward went to Antioch for the same reason. After he retired from food brokerage, he had a long and good association with the Kansas City Opera.”

Ebb’s roots sprouted, said Ebb, “at Houston and Broadway.” His father was a Harry too, his mother Anna Gritz Ebb.

“They were middle-class to lower, I guess you’d say,” Ebb recounted. “My father sold clothes and furniture on the installment plan on the Lower East Side. My mother, a housewife. My two sisters, nothing extraordinary. There was never, ever any music in my family.”

Ebb went to New York City public schools and graduated from NYU with a fine arts B.A.

And a master’s in English literature from Columbia.

“I came out of college and wrote for ‘That Was the Week That Was.’ An agent named David Hocker took an interest in me, and brought me to Kaye [Ballard], and Kaye brought me to Carol Channing, and I wrote special material for both of them.

“So I had some material and some reviews, and it kind of snowballed. Then I meet John.”

And the shape, sound, feel, awareness of American music began to change. At Carnegie Hall this coming Monday evening, Liza Minnelli and a bunch of other people will be demonstrating, in action, just how.