PUBLISHED BY PLUME.

Pride Week should be not simply a celebration of our collective identity in the present, but also a moment for remembering — for, as William Faulkner rightly observed, “The past is never dead, it is not even past.” But for too long, our queer past was hidden from view. Reclaiming that past is an important part of our ongoing struggle for liberation.

In the hands of a great writer, reimagining our queer past can be not simply a necessity, but a pleasure — and in the gay literary canon, among my most prized discoveries has been the work of the English writer Pat Barker. Like Mary Renault and Penelope Gilliatt, Barker is one of those remarkable heterosexual women whom the Brits seem to produce with some regularity who can write about male homosexual love, sex, and desire and be pitch-perfect.

Yet Barker’s “Regeneration” trilogy of historical novels, published over a four-year period two decades ago, is not as widely known as it deserves to be, for it is landmark queer literature that every sentient same-sexer owes it to themselves to add to their bookshelves.

British author’s reimagining of queer life in the Great War offers unmatched insights

The three novels — “Regeneration,’ “The Eye in the Door,” and “The Ghost Road” — are set in the Great War, as the Brits are wont to call World War I, and give us an extraordinarily rich, truthful portrait of what it was like to be queer in England in those years, when the tragic persecution and imprisonment of Oscar Wilde were still everyday threats hanging over male homosexual life and the laws that sent him to Reading Gaol still in force — as they remained until 1967.

These meticulously researched novels have as their axis the work of William H.R. Rivers, the psychoanalyst who pioneered the treatment of soldiers suffering from what we now call Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder that left them with a variety of life-destroying physical and psychological symptoms.

Barker peoples her novels with both real historical personages and fictional ones. In the former category, we have Rivers himself, while among his patients are the war poets Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen, both queer, and celebrated homosexual friends of theirs, including Robbie Ross, Wilde’s most loyal friend, sometime lover, and literary executor, the novelist Robert Graves, and the writer Lytton Strachey. A central character of “The Eye in the Door” is the fictional Billy Prior, intensely bisexual, whose psychological, affectional, sexual, and political life stands in contrast with Sassoon’s pure homosexuality and Rivers’ tepid asexuality.

In “The Eye in the Door,” we also become acquainted with the repugnant anti-homosexual crusade of Member of Parliament and writer Noel Pemberton Billing, another real-life figure who propagated a widely-accepted conspiracy theory in which Kaiser Wilhelm’s Germany possessed a Black Book with the names of 47,000 “perverts” well-placed in British society and politics. In Pemberton Billing’s mad theory, the Germans planned to “exterminate the manhood of Britain” by luring men into homosexual acts and “”propagating evils which all decent men thought had perished in Sodom and Lesbia,” as he wrote.

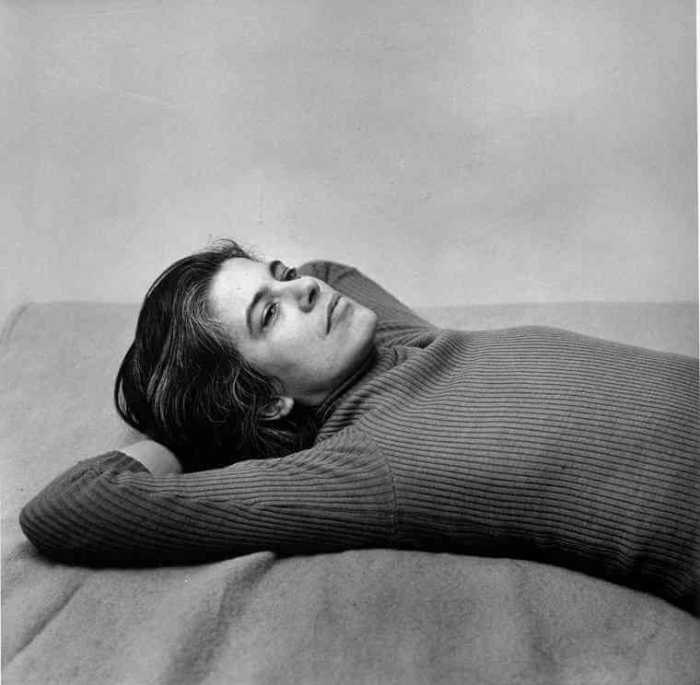

Siegfried Sassoon in a 1920 photograph by Bassano. | NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY/ LONDON

Pemberton Billings also targeted the wives of leading political figures whom he accused of lesbianism, including the wife of Prime Minister H.H. Asquith. When he leveled the same charge against the actress Maud Allan, who had appeared in a private production of Wilde’s play “Salome” organized by Robbie Ross, she sued for libel. The resultant trial became a popular media sensation and contributed mightily to the anti-homosexual hysteria of the time. Lord Alfred Douglas, Wilde’s great love “Bosie,” was well on his way to self-loathing and testified on behalf of Pemberton Billings! When the MP prevailed in a court decision against the actress, this seeming judicial confirmation of Pemberton Billings’ deranged fantasy only intensified the anti-gay feeling in the country.

Barker’s novel recreates better than any historian has done the impact of Pemberton Billings’ anti-gay ravings and the climate of near-frenzy they created in the anti-German public toward unashamed queers like Sassoon and Ross and on those who, like Wilfred Owen, were more ambivalent about their same-sex orientation. Her expert blending of real events and the fictional breathes verisimilitude into this forgotten chapter of gay history.

In “The Ghost Road,” Barker focuses on Rivers’ therapeutic work with the fictional Prior, an officer from the working classes (in contrast with the upper-class Sassoon in “The Eye in the Door”). The novel recounts Prior’s promiscuous adventures with both sexes.

Rivers’ official task was to get his psychologically damaged patients back into condition to return to the front. I’ve always found one of those patients, Sassoon, and his real-life struggles quite appealing. Although he had volunteered for military service at the outbreak of the war and distinguished himself by what Robert Graves later described as acts of “suicidal bravery,” for which he received the highest military decorations, at the end of a spell of convalescent leave Sassoon declined to return to duty. Instead, encouraged by pacifist friends like Bertrand Russell and Lady Ottoline Morrell, in 19l7 he sent a letter to his commanding officer entitled “Finished With the War: A Soldier’s Declaration.” Forwarded to the press and read out in Parliament by a sympathetic MP, the letter was seen by some as treasonous.

“I am making this statement as an act of willful defiance of military authority,” Sassoon wrote in condemning the war government’s motives. “I believe that the war upon which I entered as a war of defense and liberation has now become a war of aggression and conquest.” He threw his war medals into the River Mersey.

But rather than court-martial Sassoon, the War Ministry sent him for treatment for “shell shock” to Rivers’ war hospital at Craiglockhart. After Rivers’ treatment, Sassoon decided to return to the front because he could not abandon the men who had been under his command. He was almost immediately wounded by friendly fire, when he was shot in the head after being mistaken for a German.

Sassoon survived and went on to a prolific career as a novelist and memoirist. Some years ago, I read his three volumes of memoirs, the much acclaimed “The Old Century,” “The Weald of Youth,” and “Siegfried’s Journey.” Sassoon’s mordant, ironic war poetry, in which he satirized the bloody, useless, vainglorious war in which he’d distinguished himself in combat, is admirable.

But nothing so became Sassoon’s war conduct as his abandoning participation in that terrible conflict, and under Parker’s oh-so-talented pen he lives again for us in all his courageous inner conflicts. It is no exaggeration to say that Sassoon is a queer hero for the ages.

Certainly Barker’s “Regeneration” Trilogy — the final volume of which won the Booker Prize, Britain’s most prestigious literary award, in 1995 — gives us an insight into the social lives and networks of homosexuals among the educated classes in the early 20th century. But it also constitutes a body of anti-war writing that brings home to us the horrific torture and slaughter that World War I’s trench warfare, under command of generals throwing away their soldiers’ lives with 19th century tactics, inflicted on millions. It was a simply appalling war, and one whose effects are with us still today.

“Regeneration” was made into a 1997 film by Gillies MacKinnon (released in the US under the title “Behind the Lines”) and starring James Wily as Sassoon and Jonathan Pryce as Rivers. The film lacks the sweep and power of Barker’s wise and enriching novels, and also downplays the homosexuality in the story.

Pat Barker’s own life has a Dickensian quality to it. Born in 1943, she grew up as the illegitimate child of a working class family who were “as poor as church mice,” as she has said, but as an avid reader from a very young age won a series of scholarships, eventually taking a history degree at the London School of Economics. Barker began to write fiction in her 20s, but her first three novels went unpublished, and, she has said, “deserved to be.” But she flowered in “Union Street,” her first published novel, one about working class life, which won her the patronage of Angela Carter, a feminist considered one of Britain’s foremost post-World War II novelists. (“Union Street” was made into the 1989 Hollywood film “Stanley & Iris” starring Robert De Nero and Jane Fonda, but Barker has said the movie bears little relationship to her novel.)

Barker turned to historical fiction because, she has said, “I think there is a lot to be said for writing about history, because you can sometimes deal with contemporary dilemmas in a way people are more open to because it is presented in this unfamiliar guise, they don't automatically know what they think about it, whereas if you are writing about a contemporary issue on the nose, sometimes all you do is activate people's prejudices. I think the historical novel can be a backdoor into the present which is very valuable.”

That is certainly the case with Barker’s “Regeneration” trilogy, which must rank as great queer literature, filled with wisdom and lessons for us today. Thankfully, all three volumes of it are still in print and easily available in paperback. I cannot urge you too strongly to read them.

REGENERATION | THE EYE IN THE DOOR | THE GHOST ROAD | By Pat Barker | Plume | $16 each in paperback