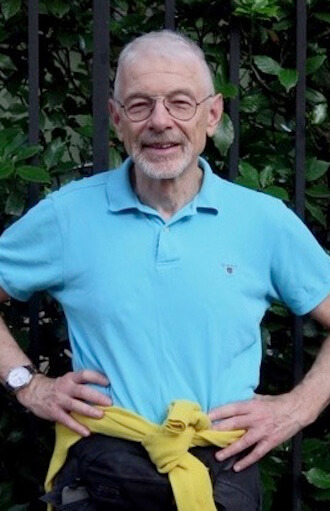

Perry Brass in the West Village’s Jefferson Market Library Garden. | RICARDO LIMON

About five days after my June 14 robotic-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy at Mount Sinai Uptown, things changed.

My “honeymoon” with the surgery was over.

The day after I’d left the hospital, I was popping out of bed, eager to start life again, going on the long recovery walks Dr. Ash Tewari, my surgeon, had recommended.

Now, I was exhausted. I couldn’t understand why; it seemed that I should have more energy not less. Then I realized I must have been working on some residual energy left inside me from before the operation. It seemed completely gone. I was wiped out most of the day; all I wanted to do was nap. Writing became difficult, but I managed it.

An invader in the pleasure dome: final in a three-part series

The Foley catheter inside my urethra began to really hurt, especially at that point of abrasion where it exited my penis. I called Dr. Tewari’s office and spoke with a physician’s assistant who told me to push my penis down the tubing as far as I could and use Vaseline to lubricate the plastic and reduce abrasion. Make sure the tubing was clean, he warned me, by using alcohol pads on it. I did this several times a day. It still hurt badly. I wondered if I was experiencing a catheter infection, a common occurrence, but there was no fever, which meant I was doing okay.

I thought: how do “normally” American, red-blooded hetero dudes who are brought up to abhor their own junk deal with handling it the way I had to repeatedly throughout the day? I had to touch, inspect, clean, and lube it all the time. Puzzling.

A day later, my penis started to swell. Overnight, it tripled in its circumference. Ditto for my scrotum. It looked like the plastic catheter was simply pushing into this repulsive mass of flesh that had kidnapped the organ I’d started out with. I emailed my friend Ricardo Limon saying my cock looked like “some weird animal you’d buy at a discount pet shop at Walmart.” My husband Hugh, a doctor, said, “If anybody ever needed pictures of elephantiasis of the penis, I’d tell them where to go.”

Taking a shower was awful, but I had to make sure everything stayed as clean as I could manage. I spoke with Dr. Avinash Reddy, the physician on-call in Dr. Tewari’s office; he said that this kind of swelling was common with catheters.

“Don’t worry,” he assured me. “It will go down as soon as we take it out.”

I asked him if I could have it out two days early.

No, he said, “Your bladder is still getting used to not having a prostate.”

By this time, walking was impossible: I was in too much pain. The transition from sitting to standing was howl-provoking. I kept thinking about that movie with Richard Harris, “A Man Called Horse,” where he was strung up by his chest; I felt like I was being strung up by this thing inserted in my swollen dick. I took 800 mg ibuprofen, but resisted taking Percocet, an opioid; I couldn’t stand being like this and constipated as well.

I spent a lot of time reading and just staying put, getting up only when I had to, but managing to do some simple stretches for my back. Two days before the catheter was set to come out, on June 23 — a date I’d highlighted in my calendar — I was started on another prophylactic round of ciprofloxacin, an antibiotic. It played havoc with my gut; the night before my appointment I had diarrhea.

The morning of the 23rd, I felt that I’d never make it from Riverdale to Tewari’s office at Madison near 59th Street without a lot of help. I swallowed one Percocet. The bottle said a “normal” dosage could be two. I am extremely drug-sensitive, but I was ready to abandon any good sense. I took another.

A few minutes later, I started floating out of our apartment. Negotiating the nine flights of stairs from the street to the train platform at Spuyten Duyvil was easy. Hugh and I got to Grand Central, and I thought: “Everything is so beautiful here, I can’t imagine anyone not wanting to live in New York.” We took a bus from 43rd and Madison up to 59th, and a short while later I was in one of Tewari’s examining rooms and a young woman, one of his physician’s assistants, easily slipped my catheter out.

I felt nothing.

I was asked to pee, and everything came out beautifully, without a drop of blood. I was told that I needed to come back to the office two hours later and pee again — just to make sure that my bladder was working.

Hugh and I walked out onto East 59th Street to have lunch, but quickly I was dizzy. We walked into the Argosy Book Store, and I sat down while Hugh browsed. I could not keep my head up; the dizziness accelerated. We made it to a coffee shop, where Hugh had lunch and I had a Coke. I managed to get to a bathroom close by, and threw up, thinking that would be the end of it.

What followed was eight hours of intense, constant vertigo and nausea. It had nothing to do with my stomach, but only my head: I felt like a small child trapped on a whirligig spinning faster than I could stand. Back at Tewari’s office, all I could do was throw up. I told them about taking the Percocets, and was told this has been known to happen — but nothing quite so extreme. Tewari prescribed Zofran, an anti-emetic. As Hugh and I took the train back to Riverdale, I couldn’t sit on the train but had to stand, since every time I tried sitting I would vomit again.

With the help of the Zofran and a Valium, the vomiting stopped. But I experienced morning nausea for the next four days. Dr. Reddy had been right: the swelling did go down fast. I felt normal again, and also horny. Cialis is part of a post-op routine to open up the passageways of the urethra and seminal vesicles. After a radical prostatectomy men can no longer have external ejaculations, but experiencing desire and erection is important — and a sign the operation was successful.

Three weeks after the prostatectomy, I had my first orgasm. By myself. Fantastic. I glowed. I wanted to tell Tewari right then and there.

A few days later, I attended a Hell’s Kitchen benefit barbecue to support the “I’m From Driftwood” LGBTQ autobiographical storytelling project, had a lot of drinks (non-alcoholic), and needed to pee. I couldn’t. Nothing came out. I tried several times, knowing that after this much liquid I should be able to void my bladder. I told Hugh about it, and he said not to worry. As I tried squeezing my penis to see if I could extract any blocking scar tissue, a short, stinging trickle eventually appeared. I called Dr. Tewari’s emergency line and Dr. Reddy immediately started me on ciprofloxcin again. The next day in the office, he scanned my bladder and told me it wasn’t filled. Good news.

“These things are normal,” Reddy said. “You’re having a delayed infection from the catheter. Very common.”

I understood: This recovery is not happening in a straight line; all sorts of setbacks and loop-arounds make me realize this.

By late July, leaking something terrible and going through endless changes of adult diapers, I saw Dr. Steve Kaplan, another urologist in Tewari’s office who deals with urinary issues. He put me on Vesicare, a drug that relaxes the muscles around the bladder, and prescribed Pelvic Rehab, a series of electronic-probe-assisted sessions that strengthen the floor muscles that undergird the pelvis.

One of his techs also took blood for a PSA, my first after the operation. This test is critical. With no prostate, your PSA should go down to “0.” If it’s 0.1 or higher, that’s a sign that there are still cancer cells — that will need treatment — in the organs that had surrounded the prostate. If such a reading results, another PSA might be taken a month or so later to determine if the first one was just a fluke — or if radiation, chemo, or hormone therapy are called for. I tried not to think too much about what the result would be as I practiced Kegel pelvic floor exercises at home and began seeing friends again, going to the theater, and generally having a life.

A week later, I finally got a call from one of Tewari’s physician’s assistants.

“Congratulations,” she said. “Your PSA is 0.04. That means there is no detectable cancer in your body.”

I felt like I could breathe again — and was very happy. I’m still dealing with urinary leaking problems, but after weeks of Pelvic Rehab and Kegels, that is tapering off.

Like many other prostate cancer survivors, I feel like the disease segmented my life into the diagnosis, the operation, and its after-effects.

I also feel very fortunate. In the past, many men were left with extreme erectile dysfunction, constant urinary incontinence, and/ or bowel problems as a result of prostate cancer. I was also lucky to have my cancer diagnosed at a point where it had not spread and I was still strong and resilient enough to withstand a major operation. Being gay with prostate cancer, especially in New York, has given me more support and the opportunity to be open about my feelings and about how cancer has affected the way my body works. Elsewhere in this country, outside of areas with an active LGBT community, that opportunity likely would not have existed.

I also learned just how difficult it would have been to face this all on my own, without the close support I got from Hugh and friends like Ricardo Limon, Mark Horn, and others in my life.

There are moments when I lose track of what I’ve been through — that I had cancer. That I still have to be monitored for years, and will have some side effects from the operation — side effects that will color my life but not ruin it.

And then there are moments when I want to forget all about it, want to be “normal” again, and stop focusing on cancer. I would like, simply, to face the rest of my life without thinking about it.

But I also realize that will be impossible.

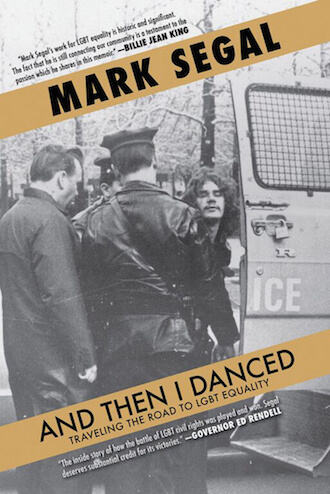

A gender rights pioneer and award-winning writer, Perry Brass has published 19 books, including poetry, novels, short fiction, science fiction, and bestselling advice books (“How to Survive Your Own Gay Life,” “The Manly Art of Seduction,” “The Manly Pursuit of Desire and Love”). A member of New York’s radical Gay Liberation Front, in 1972, he co-founded, with two friends, the Gay Men’s Health Project Clinic, the first clinic on the East Coast specifically serving gay men that is still operating as the Callen-Lorde Community Health Center. Brass’ work, based in a core involvement with human values and equality, encompasses sexual freedom, personal authenticity, LGBT health, and a visionary attitude toward all human sexuality.