A new Natalie Wood biography explains the rebel star’s gay cause

Judy: All my life, I’ve been—I’ve been waiting for someone to love me, and now I love someone. And it’s so easy. Why is it so easy now?

Jim: I don’t know; it is for me, too.

Judy: I love you, Jim. I really mean it.

Jim: Well, I mean it . . .

Who can forget Natalie Wood and James Dean as Judy and Jim in “Rebel Without a Cause?” Two dysfunctional, suburban teens with a closeted pal named Plato (Sal Mineo), try to make sense of a society where your dad doesn’t understand you, ignores you, or worse––wears an apron in the kitchen.

But to watch “Rebel” (1955), “Splendor in the Grass” (1961), “West Side Story” (1961), “Miracle on 34th Street” (1947), or the hyper-emotional “All the Fine Young Cannibals” (1960) is to revisit how Wood once generated so much acclaim. Natalie won the Golden Globe award for Most Promising Newcomer in 1957. She was in a three-way-tie though with Carroll Baker and Jayne Mansfield.

If you’re not a big fan of Russian history, including the Bolsheviks, the Winter Palace, and Nicholas II, this biography begins with a bit too much detail on Wood’s ancestry. At times you think this is going to be the life story of Anastasia. There is a reason, though, for all the textbook data. Lambert, who’s also written about George Cukor, Nazimova, and the making of “Gone with the Wind,” is building a case here for Natalie’s mother’s manic drive.

Russian immigrant Maria Stepanova Gurdin had an unbridled ambition that helped make her daughter both a star and an emotional mess. Wood’s insecurities led her later to date bisexual and gay men including director Nicholas Ray and actor Nick Adams.

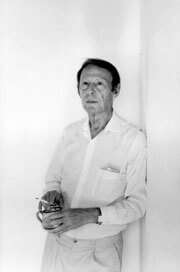

Lambert, a well-known gay man in Hollywood circles, wrote the novel and the screenplay for “Inside Daisy Clover” (1965), which is how he became friends with Natalie. She starred as Daisy, the child star who winds up married to a homosexual played by Robert Redford.

The studio toned down the gayness in this flick, but Lambert does not spare any details in Natalie’s bio. It frequently bristles with homo-trivia. Her secretary, for instance, was Mart Crowley, who went on to write “Boys in the Band.” Natalie, herself once almost starred as a closeted lesbian in “Cassandra at the Wedding.” And then there are all the guys who used Natalie as a beard. Even her two-time spouse Robert Wagner has been rumored to be bisexual, some going so far as to say he was making love to actor Christopher Walken on the boat off which Wood drowned.

Lambert, who gained Wagner’s cooperation in writing the biography, argues that Wagner is as straight as a ruler, and that Wood’s death was an accident.

Lambert even gets Wagner to address the queer intimations. The stories of his gay sexcapades apparently all started when he became the client of the famous agent Henry Willson, who had a “reputation as a sexual predator.”

“Over the years,” Wagner notes, “I’ve been linked sexually with Jeffrey Hunter, Burt Lancaster, Dan Dailey, Clifton Webb and, my God, even Clark Gable.”

Lambert adds, “[Wagner] could shrug the rumors off because he felt secure about his own sexuality, and like Natalie had many gay friends throughout his life.”

“But why did Wood have so many gay men in her life?” I asked Lambert last week. In a delicious British accent, the author replied: “I have two answers to that. One is specific to her, and the other is specific to a lot of actresses. Actresses like gay men because they know there’s going to be no problem of them making a pass, and therefore they feel that they are not being used and all that stuff.

“In Natalie’s case,” he continued, “she grew up in a drastically dysfunctional family, feeling like an outsider, and she responded across the board not only to gay people as outsiders but to anybody who felt alienated in some way because of their life experiences. She particularly responded to gays because they were very entertaining about it, which some of the others were not. She didn’t like self-pity or anything like that. What she did like were people who would say the unconventional things and be entertaining about it. She was a great shit kicker, and in part, gays tend to be, too, and she liked that.”

Lambert is known to kick the gay shit as well, having been best friends of Christopher Isherwood, Cukor, and Tennessee Williams among dozens of others. He’s authored the Oscar-nominated screenplays for “Sons and Lovers” (1960) and “I Never Promised You a Rose Garden” (1977). But what could top his teleplay for the camp classic, “Liberace: Behind the Music” (1988)?

“That was more than a fun experience,” Lambert laughed. “I didn’t know Liberace, and yes, in a way it was campy. But it was again something that interested me because here again was another person who was outrageously gay and a public figure. Until the scandal sheets got ahold of him, he got away with it, and it was wonderful. I looked at a lot of footage of him, his television shows and stuff, and all these sort of middle-aged ladies loved him. They were so in denial. He could be absolutely outrageous and was. He’d come down in all this mad drag, and they would laugh and love it. They would feel maternal and tender toward him as well as being amused by him. I found that fascinating. That couldn’t happen now. You’d be outted instantly.”