The spellbinding, brilliant, and, to quote the song from the show, “perfectly marvelous” revival of “Cabaret” on Broadway is nothing short of genius. Director Rebecca Frecknall has blown the dust off the often-revived 1966 musical with the force of a hurricane. Like Daniel Fish’s bold reimagining of “Oklahoma” in 2019, Frecknall has fearlessly looked into the darkest reaches of the material and come up with cultural context, vision, and theatricality that is profound — and wildly entertaining.

It’s no easy task. “Cabaret” is, to many, forever identified with Liza Minelli’s Oscar-winning performance in Bob Fosse’s 1972 movie, which was star-driven and relied heavily on Minelli’s brand of razzle-dazzle. The Roundabout production, with Alan Cumming as the emcee, was a Broadway sensation in 1998 and 2014. Yet none of these scraped up the veneer — albeit delightfully tacky — of the Kit Kat Club and looked unflinchingly into the diseased soul of a world on the verge of cataclysm. Frecknall’s view is daring, particularly in a commercial venue, to reinterpret a beloved, familiar show, but therein lies the thrill.

“Cabaret” is set in Berlin in 1929 at the end of the Weimar Republic as the Third Reich is rising in Germany. The centerpiece is the Kit Kat Club, a seedy joint where permissive sexuality and gender fluidity are the norm, where denizens revel in the so-called excesses (prompted in part by existential crises that arose from WWI) that would give Hitler the impetus to destroy anything that challenged “traditional German values.” In and among this demi-monde, overseen by the Emcee, are Sally Bowles, a British entertainer of questionable talent but lots of personality, and Clifford Bradshaw, an American Writer looking to find his voice in Berlin. At the rooming house where Clifford stays — and where Sally virtually forces herself into his room — we meet Fraulein Schneider, an aging spinster whose abiding talent is survival, Herr Schultz, the Jewish fruit seller who is courting Schneider, and Fraulein Kost, a woman who supports herself by “entertaining” sailors. Each of these lost souls is caught up in, and damaged by, a world in turmoil.

None of these characters is more vulnerable or lost than Sally. In Gayle Rankin’s spectacular performance, Sally is frustrated, angry, trying desperately to be special, and her tragedy is that her drive to be something more than ordinary blinds her to what is coming. Rankin’s phenomenal rendition of the title song is fully integrated into the character, emotionally complex, and wholly original.

Clifford Bradshaw, played with intelligence and sensitivity by Ato Blankson-Wood, wrestles with his sexuality, his love for Sally, and his grief at his own powerlessness. His escape has costs, but he finds his voice. It’s a bittersweet conclusion.

Herr Schultz’s tragedy is that he places too much faith in the system to right itself in the face of rising insanity. In a heartfelt performance by Steven Skybell, Schultz’s intelligence and belief in Germany will ultimately be his undoing.

Fraulein Schneider, on the other hand, is a survivor. She will survive, even when it means walking away from the possibility of love and happiness. Bee Neuwirth is heartbreaking in portraying Schneider’s awful choice but in the hardness the world has imposed upon her. She gives the character new depth and contextualizes the suffering at the core of survival. Natascia Diaz is wonderful as Kost, another marginalized person just hoping to get by.

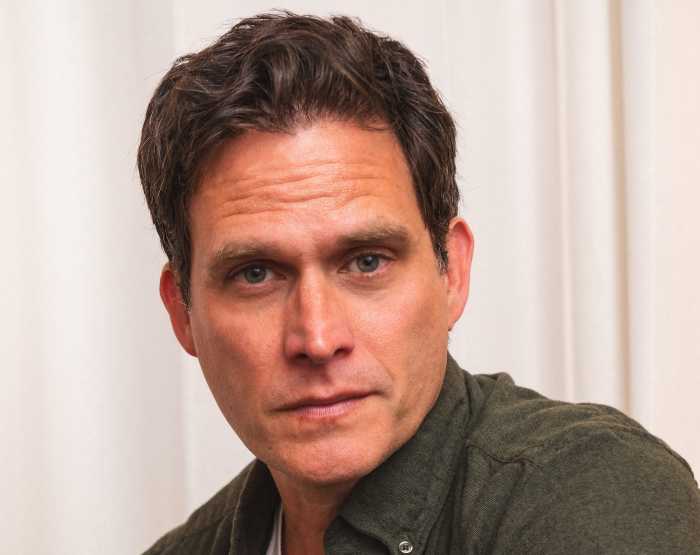

It is, however, in the director Frecknall’s interpretation of the emcee that gives this piece its power. If you’re going to portray quintessential evil, casting the nearly angelic Eddie Redmayne is a bold move. Whereas the emcee is often a painted figurehead, Frecknall has left Redmayne’s face unpainted but outfitted him in costumes that tell a story of German art history in themselves. When he first appears, he is Der Struwwelpeter (also known as Shockheaded Peter), a ghoulish 19th century character designed to terrorize children into good, compliant behavior. We next see him in a black, quasi-robotic costume that could be right out of Fritz Lang’s 1927 German expressionistic, anti-capitalist film masterpiece. “Metropolis.” Fittingly, it’s how he sings the song “Money.” Next, we see the emcee as a clown — as Hitler was often portrayed outside of Germany as he gained power and the world did not take him seriously. Finally, the emcee is the perfect, blond Aaryan. Redmayne gives the performance of a lifetime — adorable, creepy, and unflinching. The evolution from superficial clown, to symbol, to monster is shocking, and it’s even more harrowing as the audience just sits there and watches it happen. It’s this level of meta-artistry that ultimately makes this “Cabaret” extraordinary and historic.

The August Wilson Theatre has been transformed into the Kit Kat Club by Tom Schutt, who also did the elaborate costumes that evolve from riotous color and inescapable excess to drab conformity, draining every character of their individuality. Isabella Byrd’s lighting design is outstanding, and sound design by Nick Lidster for Autograph is sharp and precise.

Of course, the political resonance with our current time is inescapable. We minimize and ignore a rising right wing at our own peril. By all means, see this magnificent “Cabaret,” but take it as a cautionary tale.

“Cabaret” | The Kit Kat Club at the August Wilson Theatre | 245 West 52nd Street |Tues, Thurs, Fri 7:30 p.m.; Weds, Sat 2 & 8 p.m.; Sun 3 p.m. | (Doors open 75 minutes prior to curtain for lobby entertainment, cash bar.) | Tickets from $139, dinner packages available | 2 hours, 45 mins, 1 intermission