Writer/director Isao Fujisawa made a remarkable debut — and his only film as director — more than 50 years ago with “Bye Bye Love,” a queer lovers-on-the-run road movie. The 1974 film, which was presumed lost, was rediscovered in 2018 and has been gloriously restored. It will have its American theatrical release in New York City Jan. 17-19 at the Metrograph Theater as part of a three-film program showcasing the 83-year-old director.

The story is simple. Utamaro (Ren Tamura) has just broken up with his girlfriend when he is approached on the street by Gîko (Miyabi Ichijô) who asks him to help her. Gîko is, it turns out, being chased by the police for shoplifting. After Utamaro is arrested for obstructing justice, he manages to steal the officer’s gun and elude him. Reconnecting with Gîko, he falls in love with her, and they embark on a madcap romantic adventure.

As they get to know each other, Utamaro is initially surprised to discover that Gîko is “actually a man.” “Bye Bye Love” raises the issue of gender in earnest when Gîko describes her relationship with Utamaro as “a love triangle between you and the male and female me.” This prompts him to ask her, “Why aren’t you a woman?” to which Gîko’s responds, “Why do I need to be a woman?” The exchange suggests how forward thinking the film was 50 years ago.

The plot kicks into gear when Gîko’s “Yank” boyfriend, Nixon (Enver Tempai), a US Embassy official, catches her with Utamaro. This prompts an act of violence and forces the lovers to steal a car and go on the lam.

“Bye Bye Love” captures the freewheeling nature of the rebellious characters who refuse to conform to social expectations. Utamaro is longhaired and nihilistic; Gîko is genderfluid and deliberately subversive. (Viewers can fill in their own thoughts about her relationship with Nixon.) These characters are an appealing couple who commit petty crimes—Gîko refuses to work or to pay for anything—and occasionally kill people.

Fujisawa is also defiant with his approach to telling the story. He employs jump cuts to convey the frenetic nature of the relationship and the excitement of their being on the run. Characters break into song from time to time. (Gîko sings about sex workers in one sequence). Paint is splashed on the camera during a fight scene to express the anarchy of the moment and the youth movement of the decade. And the organ-heavy soundtrack gives off a real 1970s vibe. The film also looks great with its rich, vibrant colors. There are several moments that feature “Red, White, and Blue” symbolism to reflect American imperialism, but there is also an impactful scene involving orange paint that is meant to indicate blood in one vivid episode.

Fujisawa includes many fascinating moments in his film that will surely impress viewers. When the couple meet a touring stripper (Atsuko Ami), the camera fetishizes her nude body in a series of sexy pin-up poses. Watching the stripper in closeup—most notably when a shot of her tongue and lips fills the screen—imbues the film with a real experimental quality. “Bye Bye Love” was very much of its time but also ahead of its time.

Likewise, a later sex sequence involving a threesome with a sex worker (Satomi Oki) is visually dazzling as Utamaro, Gîko, and their guest wrap their naked bodies up with electrical cords that bind their feet and torsos together, with the wire ends in their mouths. It is a fabulous sequence emphasizes the experience of pleasure and exposes the characters’ genitals.

Fujisawa also features an exciting shootout as Utamaro and Gîko are discovered by the police, as well as surreal moments such as one where the couple take a bicycle they stole through a river only to magically appear on a distant shore somewhere else. The film is thoroughly engaging even as it operates on its own cockeyed logic. Viewers will easily root for the characters to get away with their crimes, which include stealing food and gas, or pulling a gun on hotel clerks.

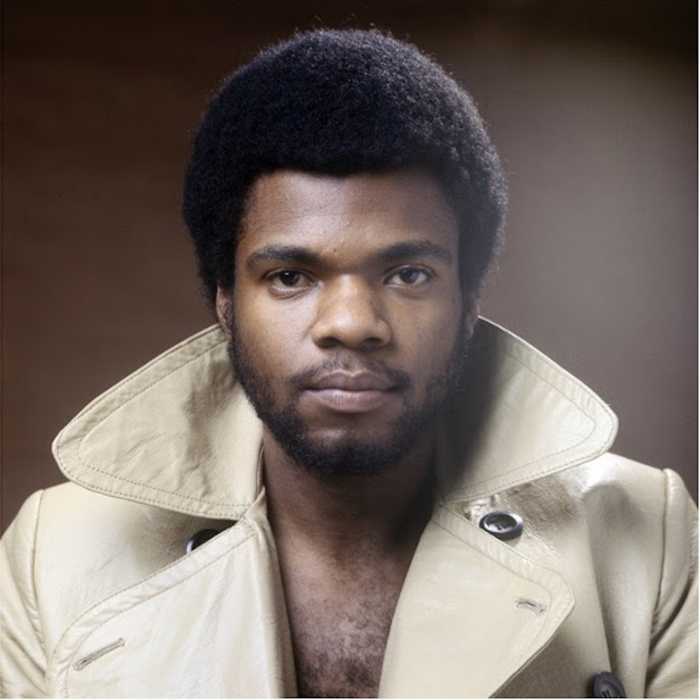

The characters take viewers along for the ride, and both Ren Tamura as the carefree antihero Utamaro and Miyabi Ichijô as Gîko have a compelling screen presence. Their romance is both impassioned and rocky, but this generates a nice tension as the story unfolds.

A fascinating cinematic artifact, “Bye Bye Love” is a reissue worth discovering.

“Bye Bye Love” will screen Jan. 17-19 at the Metrograph Theater, 7 Ludlow Street, along with 35mm prints of two films — “Woman in the Dunes” (1964) and “The Face of Another” (1966) — directed by Hiroshi Teshigahara. Isao Fujisawa worked as an Assistant Director on both.

“Bye Bye Love” | Directed by Isao Fujisawa