The Prismatic Ground festival, currently in its fifth year, has a very specific mission: showcasing experimental documentaries. It’s always resisted defining exactly what that means. Since the first installment took place online (by necessity, in the spring of 2021), Prismatic Ground continues to make much of its lineup available for free via its website. The festival is organized in five “waves,” grouped loosely by theme. Inney Prakash’s programming leans towards explicitly political filmmaking: The “Some Strings Pts. V & VI” shorts program protests the violence inflicted upon Palestinians. With four theaters, it crams many films into just a few days. (In addition to the work reviewed below, this year’s lineup includes films by queer directors Pierre Creton, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Grace Mitchell, and Sophia Theodore-Pierce.) Criterion Channel subscribers can still catch up with highlights from previous festivals.

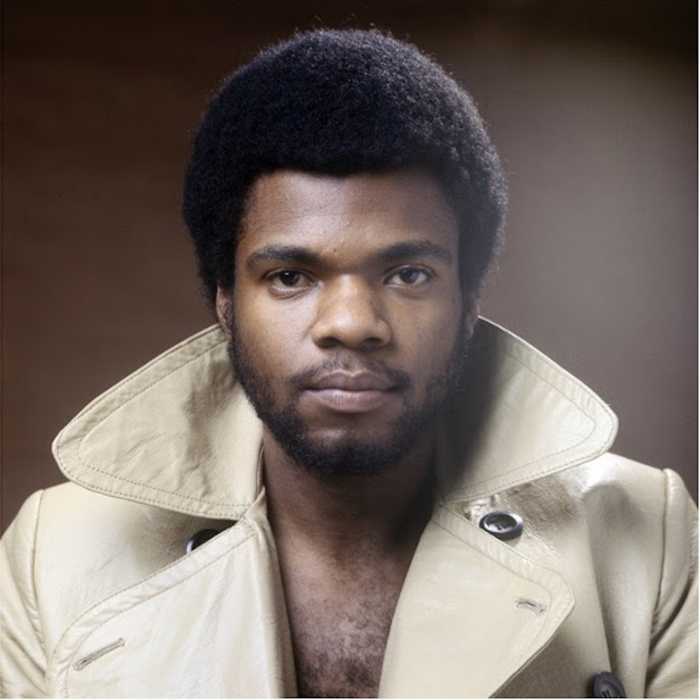

Fakir Musafar, the subject of trans director Angelo Madsen’s documentary “A Body To Live In,” was one of the prime movers behind the “modern primitives” subculture that popularized body piercing and more elaborate modifications. Playing at the Metrograph on May 4, it closes Prismatic Ground. “A Body To Live In” accomplishes something rare: utilizing images which would read as body-horror or even “torture porn” in another context, but taking out the violence. With scenes of people sticking their knives in their torsos and hanging from nipple hooks, it sounds like a very difficult watch. It actually goes down relatively easy, not through denying the physicality of such practices but because it makes a case for the merit of pain as a means of exploring our bodies.

Born Roland Loomis in 1930, Musafar took a long path towards exploring his desires. Madsen turns towards photos and home movies taken by Musafar; the early ones document a growing interest in BDSM, even if it was pursued alone. He found a partner, Cleo, who was also interested in the same practices and started to hold piercing-and-tattoo parties with a social circle of queer men. His own sexuality and gender are never fully pinned down by the film, but he explored his attraction to femininity in private photos.

Less positively, Musafar drew his ideas about spirituality and ritual from indigenous Americans, the Middle East, and India. Taking his pseudonym from a Sufi mystic, he pulled them out of their original cultures, playing mix-and-match with them. Desperate to find something deeper than the blandness of white American life in the Midwest, he felt entitled to profit from indigenous culture.

Madsen’s editing takes a psychedelic approach to archival material. While he avoids crude shock tactics, “A Body to Live In” really succeeds by showing what Musafar got out of sticking hooks in his skin. Many of its clips show people with looks of ecstasy and peace on their faces. Musafar lamented the commercialization of piercing, seeing it as inherently spiritual. He saw new possibilities in bodily experiences most people would go far out of their way to avoid, acting out the “long live the new flesh” credo of David Cronenberg’s “Videodrome.”

Grace Zhang has written that her short “typhoon diary 风球日记” expresses feelings of disassociation, which led her to realize she’s trans. While that’s not stated outright in the film, it crams depths of experience into less than seven minutes. Shot over the course of two years, it treats heavy rain as a sensual, rhythmic image, beginning and ending with its pulse. (The final scene shows a person dancing to Moby’s “Why Does My Heart Feel So Bad?,” almost concealed behind pounding water.). “typhoon diary 风球日记” melts its visuals (including text), speech, noise and music down into a whole where no single element dominates. Without telling a story, it finds transcendence in an assembly of memories blurred in the rain.

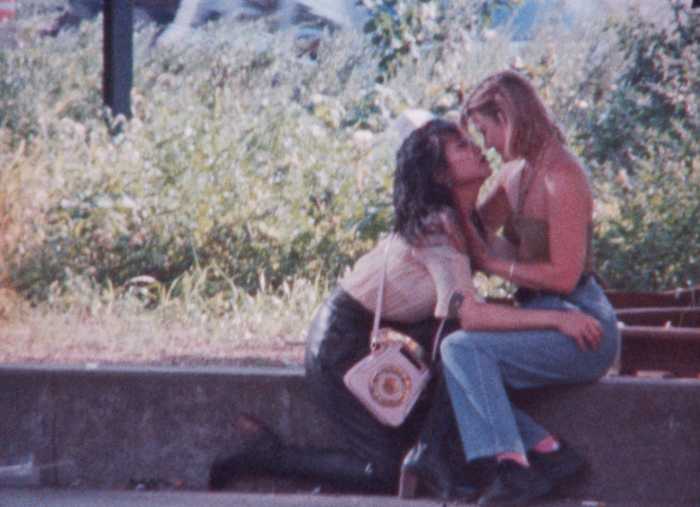

Ayanna Dozier’s trilogy “It’s Just Business Baby” receives its own program. Her three shorts, made between 2022 and 2024, are connected by their silence and the fact that they all take place in public space. A critic, film curator, and professor, she has also been a sex worker, an experience that informs these films.

“Let’s Make Love and Listen to Death From Above” films two men making out, initially shot so that only their pants and shoes are visible. It gradually moves up their bodies as they kiss and turns from extremely grainy black-and-white stock to color while they head down the street, probably to have sex in an apartment. “It’s Just Business Baby” presents two women caressing each other as one cries.

While one is a sex worker and the other her client, the film focuses on the emotions following their sex. Halfway through, it starts all over, with the actors trading places but performing the same gestures of care in a subway station. The third part of the trilogy, “Bounded Intimacy,” is its most complex and engaging film. Shooting from the roof of an apartment building, an unseen cameraperson tracks a woman on the street below. Their voyeurism is matched by their great distance from her. In the third scene, the camera now approaches her from street level. She flirts with the camera — or its operator — as it comes closer to her.

“Bounded Intimacy” imagines a queer voyeurism where desire is expressed visually, yet exchanged between women rather than imposed upon them by heterosexual men.

Prismatic Ground 2025 | April 30-May 4 | Screenings held at Anthology Film Archives, Metrograph, BAM and Light Industry | Films streaming online at prismaticground.com. Check the site for full lineup and schedule.