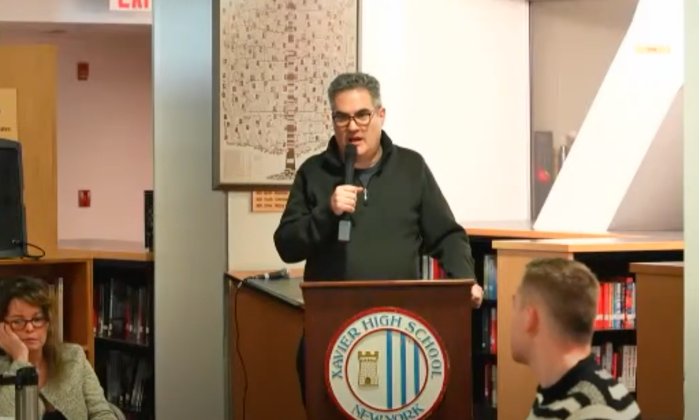

Sarah Ngu lectures about colonialism and her own family history at Forefront Brooklyn Church last month. | COURTESY OF SARAH NGU

It started with a text: “How would you guys feel if I married a woman?”

Alarm bells.

Sarah Ngu’s parents thought she “had gotten this under control.” But by this point, she already knew she was headed in a direction of self-acceptance. After the church she grew up in told her it would be wrong to marry a woman, it had taken another church to change her mind.

Ngu, now 27, grew up as a pastor’s kid. Her father pastors in a nondenominational Asian movement focused on evangelism and church-planting in communities not served by the movement.

“Looking back, it was probably a little fundie [fundamentalist], a little pentecostal,” Ngu said. “They were very much interested in multiplying churches, so they sent my dad to America to start a church.”

Moving on from fundamentalism, Sarah Ngu looked to affirming church, Christian peers

As the oldest of four kids, Ngu was often helping her dad. She sat in on strategy meetings held on Sunday evenings, listening to her father and other church leaders discuss attendance and what went well in the service.

“It was more business-oriented,” she recalled. “Like what are your sales metrics? Just like people do in sales, people say conversion metrics.”

Ngu grew up in Malaysia, where her father planted two churches. Evangelical Christianity does not have the same political conservatism in Malaysia as it does in America.

“Malaysia has socialized healthcare, no guns,” she said. “It’s more about: Do you support the corrupt incumbent party or do you support the opposition? Technically, we would be on the opposition, the radical side. But when it comes to abortion, sexuality, and gender, [my family] would be on the conservative side.”

At age 10, Ngu’s family moved to the US and settled in California. At 17, she and her family came to New York City so she could study American Studies and Political Science at Columbia University.

Sarah Ngu (foreground) with a friend at Brooklyn Pride last June. | COURTESY OF SARAH NGU

Studying at Columbia meant that Ngu had to split her brain into two parts — the Christian conservative side and the secular progressive side. While her friends were talking about Michel Foucault and Judith Butler, Ngu was wrestling with the apostle Paul’s epistles.

At Columbia, she was a part of a group called InterVarsity, a Christian campus ministry. The ministry gave Christian students a space to pray and worship together. It also held debates between Christian and atheist professors.

“InterVarsity is a little pious,” Ngu said.

Active in mental health and socialist organizing activities on campus, Ngu was closer to her secular liberal friends than her InterVarsity friends. “When that divide collapsed, it all came together,” she said.

During her time at Columbia, Ngu had a number of closeted relationships, though she recalled, “It’s hard to call them relationships because there was never a commitment in mind.” Sometimes the other woman was Christian and had her own hang-ups about sexuality and faith. The secrecy made it difficult for meaningful bonds to form.

“I’m in a relationship now,” Ngu said. “You do things together, plan for the future, introduce them to extended family, make collective decisions together about the collective unit you’ve formed.”

When Ngu was forced to keep her relationships hidden, she couldn’t turn to friends for dating advice.

“Any criticism of the relationship becomes a criticism of the existence of the relationship,” Ngu said. “The struggle becomes less about ‘let me examine if this is a healthy relationship,’ but more about ‘I need to figure out if this is moral.’”

After graduating from Columbia, paying off her student loans and moving out of her parents’ house, Ngu, in 2014, began to look for churches that affirmed gay marriage.

That’s around the time she found Forefront Brooklyn Church, a Boerum Hill LGBTQ-accepting church. Talking to the church’s pastor, Jonathan Williams, was a turning point in her journey of theology and self-acceptance.

Ngu’s experience didn’t line up with what she found in scripture.

“It seemed to me that this love thing was actually forcing me to be a better person, to incorporate another full person into this singular ego of mine,” she wrote on her blog, postfundy.wordpress.com, an outline of her movement away from Christian fundamentalism. “Love seemed to be the best spiritual antidote to the Cartesian isolation of the ego. It felt like sanctification, a kind of death-and-resurrection holiness to me.”

Ngu didn’t know why her relationship felt more like holiness than it did sin.

Being around other LGBTQ Christians also gave Ngu a different experience about what it meant to be queer.

“Everyone is gay at Forefront,” she said. “It was a total other psychological experience.”

It was because of her experience at Forefront that Ngu decided to attend the annual conference of the Gay Christian Network, which has since changed its name to Q Christian Fellowship.

At the conference, she heard stories from other LGBTQ Christians about their families rejecting them and the psychological pain it caused.

Ngu worried about how her own parents might react. They already knew she was gay, but she had so far remained conservative about her sexuality. In fact, Ngu spent nine months studying the question of gay marriage within Christianity at a fellowship called Trinity Fellows Academy.

“I felt like if I were to switch a position in my faith, it would have to be intellectually justified,” she said.

Her roommate at the time, Cat Ricketts, was surprised by how personal Ngu’s research topic was.

“I remember a lot of times praying with Sarah,” Ricketts said. “At points where it was really painful, she would cry because she was in the middle of really honest wrestling.”

At the end of the nine months, she still was in a conservative position. It took the influence of Forefront Brooklyn Church and the Gay Christian Network to make her think about the issue differently.

Once Ngu knew that her thinking and feelings were headed toward self-acceptance, she got a counselor to help her with telling her parents.

“I felt like I was cutting off my own arm,” she said. “There was no boundary between my parents and me. The pain I was causing them, I would cause myself.”

“In Asian culture there is no identity,” Ngu said. “There is just behavior and duty. You feel things, but you can only act a certain way.”

But after a lot of “theological back-and-forth,” things are looking up for Ngu’s parents.

Sarah Ngu (at r.) with other members of Forefront Brooklyn Church’ Queer Communion in last year’s Pride March in Manhattan. | COURTESY OF SARAH NGU

Since 2016, Ngu has been working with her parents about being affirming. In the past six months, they met her partner, Abby Shuster, and they like her. She’s trying to find other Asian Christian women with LGBTQ children to talk with her mom.

“We’ll see what happens,” Ngu said. “I don’t think my parents will be affirming any time soon, but I want to get to a point where they have a less black and white view of things.”

When Shuster met Ngu at Columbia, she realized that Ngu herself had a lot of “black and white” thinking.

A Reform Jew, Shuster hadn’t met many fundamentalist Christians or Christians in general.

“A lot of those early months were about me trying to figure out how to relate to that,” she said. “She had to learn the right language to talk about her faith or how her faith intersected with other parts of her identity.”

Now Ngu splits her time between ghost-writing and helping with various LGBTQ Christian projects like Queer Communion, a group associated with her church. She also hosts the Religious Socialism Podcast.

“For her, things start as personal and become work or work and then a personal project,” Shuster said. “She figures out ways to get paid to do things she cares about.”

Ngu also helps run ChurchClarity.org, a website that scores churches’ websites on how clear they are about their attitudes toward LGBTQ people.

“I think that’s one of the projects that stands out; it has Sarah written all over it,” Shuster said. “She cares about what happens to LGBTQ people in other Christian communities, [the impact] the deception and duplicitousness of being quietly unaffirming has on individual people.”

For Ngu, being queer is now a political identity that she is committed to with pride.

“The marginalization and persecution of the church has only increased my identification with queerness or being gay,” Ngu said. “Because I’ve had to fight for it. Or wrestle with it in a way that I wouldn’t have had to.”