Labors of love from Boy George, Rosie O’Donnell, and Charles Busch

The Newest Romantics

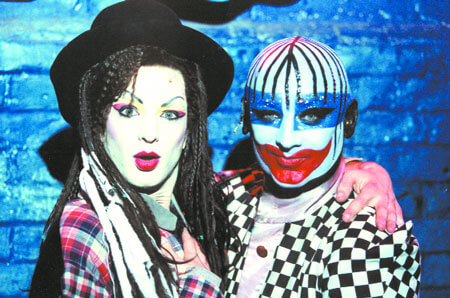

Euan Morton as Boy George and George O’Dowd as Leigh Bowery.

Some taboos cross continents. A hit musical on London’s West End, “Taboo” brings to life the U.K.’s freaky “New Romantics” club scene of the early 80s and two of its most infamous inhabitants: Boy George O’Dowd and Leigh Bowery.

Last year, Rosie O’Donnell caught the show and decided to pursue a Broadway version. She drafted out gay actor/writer Charles Busch (“Die Mommie Die!,” “The Vampire Lesbians of Sodom”) to re-write the book, along with choreographer Mark Dendy, and original West End “Taboo” director Christopher Renshaw.

As in London, the young Boy George is played by Euan Morton, who received an Olivier Nomination, while O’Dowd himself plays Bowery, a cutting-edge designer/performance artist who died of AIDS on New Year’s Eve in 1994. O’Dowd also wrote the show’s 20-plus original songs, which are sprinkled with a few Culture Club tunes.

The New York press regarded little about the Broadway mounting as taboo during the past several months. The New York Post has padded its gossip pages with items about alleged—and even some confirmed!—backstage dramas, from cast walkouts to canceled performances to rows with O’Donnell.

“Certainly those dramas did exist, they were real, and really did happen,” Morton acknowledged. “[As creative people,] we’re all egotistical, everyone wants to have their little bit of a vision put up there, and I think sometimes people take it a little too seriously and it gets turned into a huge, big thing. It was all part of the natural process of trying to put up something this big and expensive and different.”

Boy George, long a source of juicy tabloid tidbits, was more than a few times on the end of taboo, not to mention privacy, smashing. Gossip sites caught wind of a personal ad he placed online, while rumors of a sexual dalliance with Morton also circulated.

“Somebody wrote on Popbitch [a gossip website] that George and I were having an affair, which is hilarious,” Morton said. “So George e-mailed them back going, ‘That puts a whole new meaning to go fuck yourself, doesn’t it?’ which I thought was quite clever.”

Broadway’s $10 million incarnation of “Taboo” begins as two old friends—Philip Sallon (Raul Esparza) and “Big” Sue Tilly (Liz McCartney)—flashback and “narrate” their seminal club days.

Enter Boy George, an outrageous, flamboyant youth nursing dreams of fame, much like his best buddy, the glamorously beautiful and bitchy Marilyn (Jeffrey Carlson). A fellow attention-seeker, Leigh Bowery, turns his talents for bizarre fashion into shocking performance art with help from Nicola (Sarah Uriate Berry), a woman he marries.

As the years wear on, Bowery opens his own club and develops AIDS, and George forms self-destructive relationships with a bi-curious photographer, Marcus (Cary Shields), and also with drugs. Yet, when all is said and sang and done, both Boy George and Bowery leave their marks on this world and in their friends’ hearts.

“I saw it, I loved it, and I wanted to do it,” O’Donnell recalled of the original London production. “I said to the people who do my money, can I do this? They said yes and I said OK.”

Once signed on, O’Donnell felt that big changes were in order. To begin with, she felt the show involved “a little too much stereotypical bitchy queens fighting with each other. You couldn’t discern one from the other, and you never saw their real life,” she said. “And after reading books on Bowery… I wanted the real story to be in the play. I just wanted it to have more heart. That’s why we got Busch, who I knew would understand how to put the heart in a story like this.”

Busch admits he knew little about O’Dowd or Bowery, but had brushes with both, before the “Taboo” gig came his way. At the 1993 Wigstock Festival, he witnessed Bowery’s infamous “birth” act, immortalized in Barry Shils’ 1995 “Wigstock: The Movie.” Dressed like a bloated kabuki nightmare, Bowery stormed onstage singing “All You Need Is Love,” before moaning, lying down, and giving “birth” to a bloody adult baby, his wife, Nicola, before finally biting through the umbilical cord. A muse for painter Lucien Freud, Bowery was also notorious for performances involving vomit, swinging upside-down through a pane of glass, and an audience-spraying enema.

“I didn’t quite get it,” Busch admitted with a laugh about the Wigstock appearance. “Oddly enough, I’m on the conservative side in some ways, but we’re actually doing a version of the ‘birth’ in the show. It’s a very strange thing.”

Beginning their efforts together, O’Donnell and Busch high-tailed it to London, where they studied the show and spent time with the people on whom “Taboo” is based, including “Big” Sue Tilly (who wrote a 1999 Bowery biography), Nicola Bowery, and Philip Sallon. However, Busch didn’t get to meet Marilyn, whose famously bitchy temperament sabotaged his own 80s music career and—briefly—“Taboo”’s mounting. “Marilyn wasn’t easy,” O’Dowd confessed. Marilyn apparently had trouble with the term “in perpetuity” when it came to signing a contract.

“I think the character in this [production] is very much Marilyn crossed with Patsy from ‘Ab Fab,’” Busch remarked.

Mark Davies’ “Taboo” book for the London stage created Billy, a heterosexual small town photographer, as its protagonist. Through Billy’s eyes, and those of his family and girlfriend, we experience the queer “Taboo” universe. Boy George and Bowery were mere supporting characters.

“I thought that was a little screwy,” Busch recalled. “I was more interested in Boy George than this fictional guy.” So Busch shifted focus to Boy George “discovering who he is. I kept [the Billy character] but changed his name to Marcus and that love story is [still] about a gay guy who’s in love with a straight guy and, through the force of his personality, somehow gets the guy involved with him, but ultimately it’s not going to work.”

“Marcus is a composite of basically every man Boy George has ever been involved with and suffered from or tortured,” Busch noted. In his 1995 autobiography “Take It Like A Man,” O’Dowd documented at length a highly destructive yet creatively-stimulating affair with Culture Club drummer Jon Moss.

How gay is Broadway’s “Taboo”? Has it been straightened up?

“No,” O’Donnell responded firmly. “We didn’t clean it up but we didn’t dirty it down either. This is a fairly accurate representation for a Broadway venue of what these people’s lives were.”

O’Dowd, for one, attests that his own love life and the club scene’s queerness are very much a part of Broadway’s “Taboo.” His Bowery makes a grand musical entrance cruising and getting busy with men in a public toilet, sleazily screaming, “Did you see the size of that?” about a gifted trick.

“In some ways it’s gayer than it was in London!” O’Dowd enthused. “It’s emotional. The sexual aspect of gay culture isn’t really that shocking anymore because it’s so much a part of what people perceive as gay life. Men fuck each other, but the most shocking thing in the world is to see two men being intimate with each other, kissing. Interestingly, what Rosie has cleverly done in this production is centered on an emotional depth and wealth of the characters, so playing Leigh is much more interesting for me because he’s a real person with lots of ups and downs.”

Asked about his most profound moments with Bowery, O’Dowd recalled “being in this club called The Fridge in London. It was around the time of the ‘Muscle Mary’ craze. Everybody was in the gym so you had these kind of perfectly toned bodies dancing around too high a lot, much of it in the public eye… In walked Leigh, 6’2” and very large framed, pretty much buck naked except for––what do they call those vagina wigs?––a merkin, these huge glittery platform boots, this pushup bra, and a big puffball on his head. I remember looking at him and thinking, ‘You are so brave.’ People used to laugh and make comments but he wouldn’t give a shit. He really didn’t care. And he was actually quite beautiful. He had a great shape so even when his fatty bits showed they were quite gorgeous… That’s what I loved about Leigh—everything about him was a contradiction.”

O’Dowd continued, “I think of Leigh as a kind of Picasso that walked. An ordinary person will take the most surreal, disturbing work and put it up on their wall and not question it. And then you see someone like Leigh and they’ll have a real issue with that. Therein lies the hypocrisy of human nature.”

Footage of the real Bowery is projected during the show’s penultimate musical number, “Il Adore,” an element of the show O’Donnell conceived of and insisted upon.

Scottish-born Morton was working in a Tower Records when he joined the “Taboo” workshop in another role three years ago. He brilliantly embodies the young Boy George, but both and O’Dowd were quick to clarify that “Taboo” ’s Boy George is a character interpreted with artistic leeway—not an impersonation.

“One of the things I love about Euan is he evokes that kind of edginess I suppose in a way was eroded by success,” O’Dowd said. “He’s added this kind of predatory kind of quality to me. When you’re 17, you’re fearless. You think you rule the world. And you are much more spiky and edgy and go for things in a much braver way. When I watch Euan, I think I was like that. He’s a fantastic actor. He’s not doing a cartoon or caricature. If I can watch and actually care, that says a lot. And bloody hell, that voice.”