Encyclopedic and anecdotal, a volume validates an historica era

The book is a chronicle of ideas, anecdotes, and stories narrated by Queer Temperament, or QT, who hears voices “as if from forty years ago.” The stories that spring to QT’s mind come “to a conclusion, or at any rate stop, at varying points in the trajectory of the late twentieth century.”

In essence, this is QT’s memoir—thinking out loud about things he has heard, read, and seen—all relating to the subject of being queer, and disseminated in a very grand, anecdotal style that risks sounding anachronistic to today’s younger ears.

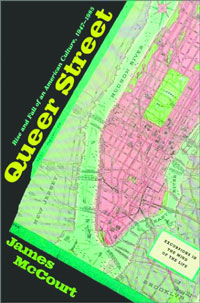

Nevertheless, the ingenuity found on Queer Street, a street that not anybody “can walk down easily: they are forever digging it up, blocking off sections of it for publicity shoots, throwing up scaffolding, and such,” is impressive.

It is a breathtaking experience to take all of what McCourt writes and comments on as he informs us that “each topic that occurs to QT along the way and over the years is elaborated like a character” and that these ideas, “in any case are initially all amalgams of and reactions to things others said.”

For instance, QT recalls Hal Call, from Eric Marcus’ “Making History: The Struggle for Gay and Lesbian Equal Rights,” saying how the armed forces “could not operate without homosexuals. Never could. Never has. And never will.” Or while discussing Melville’s “Billy Budd,” “the most homoerotic as well as the most beautiful piece of short fiction written,” QT refers to Claggart as the “queer devil adversary.” “The greatest enemy of the homosexual may now be the other homosexual,” QT muses. “Queers can do things to the self-esteem of other queers—witness the Chelsea Boys—that no heterosexual schoolyard bully, no cruel father, has ever matched.”

Such statements cut to the heart of the social and cultural crisis queer men continue to contend with today.

The end of the Second World War, which cemented America’s role as the new superpower, is the starting point for McCourt’s journey into queer life. He travels down memory lane with QT, reviewing and remembering each sight, sound, and smell along the way—from his childhood growing up in Brooklyn to Eighth Street to the Ninth Circle to the St. Mark’s Baths to tearooms to the standing-room-only space at the back of the Metropolitan Opera House. Many cultural references are examined in a dizzying prose that is both philosophical and encyclopedic.

Not only is this book a New York history lesson, it’s a queer history lesson told from a very queer-centric perspective that embraces a cast of characters including Harry Hay, Judy Garland, Bette Davis, Tennessee Williams, as well as major events like the Stonewall riots.

McCourt encapsulates the queer experience from an era that is in danger of becoming misunderstood and even forgotten. In this sense, this monumental book places an importance on the history of personal queer revelations as told by McCourt who ably captures the spirit of that significant period in history.

Not to lose sight of just where and how far we as a “movement” have come, McCourt in a display of postmodern genius delivers the essence of what his generation has come through. Hopefully, someone from the succeeding generation is already in the process of remembering––and recording––all that has transpired since McCourt’s heyday and will pick up from where he leaves off.