“Johnny Guitar,” the musical, reveals homoerotic undertones in the Wild West

Cult classics work because they appeal, in an ironic “wink-wink” manner, to the audience’s intelligence. Beneath the artifice of the best camp are sociopolitical and psychosexual complexities.

So it is with Nicholas Ray’s 1954 cow-chick flick, “Johnny Guitar,” in which McCarthyism and repressed queer longing boil beneath the Technicolor surface of a Western stewpot. When you cast Joan Crawford as gun-totin’ whore-turned-entrepreneur Vienna (even her name evokes Freud), you’re bound for subversive fun. Add desert-dry Sterling Hayden as Johnny Guitar, drifter-fighter-strummer-lover, and underappreciated (and recently deceased) Mercedes McCambridge as Vienna’s blatant nemesis/latent admirer stoking a catfight of Shakespearean dimensions, and you’ve cooked up some rich kitsch.

Not that audiences of the time appreciated it. As title singer Peggy Lee noted in a recent PBS biography, the flick was a flop. However 50 years of hindsight and a light touch do the material happy justice in a new musical adaptation at Century Center.

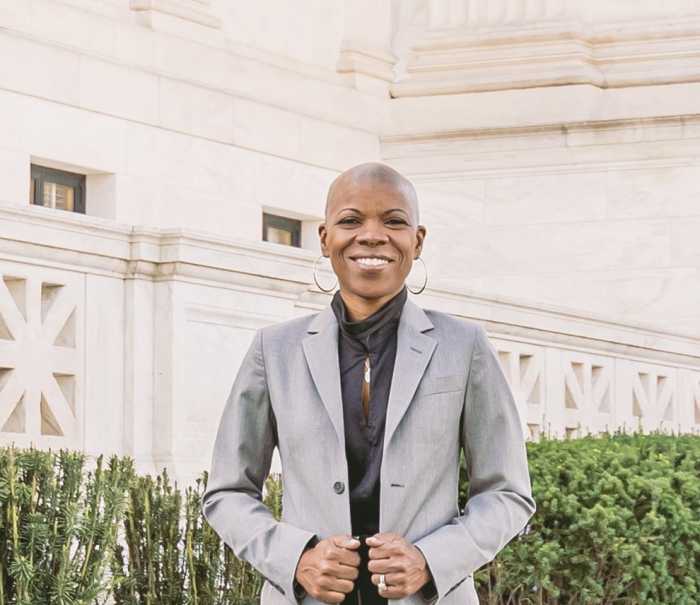

Playing opposite the epic sweep of the 1950s back lot, the era’s excess of extras, its bleeding celluloid, and Crawford’s bug-eyed charisma, director Joel Higgins––who wrote the lyrics and, with Martin Silvestri, the music––has pared this production down to its comic essentials. Judy McLane––in a short Crawford wig that lends her beauty a soft butch edge––is Vienna, the tough-as-nails tramp gone straight who, having “exchanged… confidences” with the railroad’s engineers, has invested in a saloon in anticipation of the Iron Horse’s arrival.

Ann Crumb is Emma, a crazed little whip of a woman who owns the bank and most of the land in this part of New Mexico. She ostensibly hates Vienna, not only because her power is threatened by the town’s newest diva, but because she’s in love with Vienna’s suitor, the Dancin’ Kid (Robert Evan). When a stagecoach is held up and Emma’s brother is killed, she blames the Dancin’ Kid and Vienna and promises revenge.

Meanwhile, a handsome stranger has come to town, absent guns but armed with a guitar slung across his back. He’s Johnny Guitar, aka the “gun-crazy” Johnny Logan (Steve Blanchard), Vienna’s estranged lover, hired by her “for protection” but hoping to get back into her chaps. There’s a bank robbery, a lynch mob, arson, a mountain hideout, some hardboiled lovin’ and a clawing, biting she-brawl denouement.

While writer Nicholas van Hoogstraten sloughs off extraneous characters, curbs the killin’ and adds some hammy one-liners, his book cleaves loyally to the movie’s dialogue which, though ripe with mid-century melodrama, is disturbing and macho and really not funny on film. In the play, however, just about every line pulls a laugh from the audience.

This comedy derives in part from the fact that the darker anti-Communism theme has been muted and the psychosexuality has been ramped up. Sure, Emma sneers about immigrant settlers “who can’t even speak English, ain’t got normal names,” but her xenophobia plays as a smokescreen for the shame of her polymorphous sexual desire. Crumb is excellent as Emma.

Unlike Mercedes McCambridge’s portrayal, which is wooden and bitter as a crab apple, Crumb vamps, mugs, flails, spins, accelerating Emma into a maniacal wind-up toy. She only has to stroke McLane’s arms in brief, surprised rapture––a gesture incidental to Emma’s attempt to lynch Vienna––for us to guffaw knowingly at Emma’s desire. But there’s enough restraint to the actors’ innuendo that the sexual hilarity never grows wearisome. McLane and Blanchard play 50s screen idols expertly, voices spitting drama, bodies striking poses.

The cast knows their audience. In the 21st century, even a house filled with middle aged straight couples chuckles good-naturedly at the “homotextual” undertones of moments like when a male saloon worker says to Johnny, “That’s a lot of man you’re carrying in those boots, stranger.” When Blanchard, having crooned his way à la Englebert Humperdinck through his torch song “Tell Me a Lie,” rips open his shirt, the whole house goes wild, the audience as polymorphously excited as Emma.

“Johnny Guitar” is intimate, mildly sophisticated fun, and the small venue serves it well. On the narrow stage, the witty artifice of Van Santfoord’s set becomes a running sight gag; a tumbleweed is pulled stage left by a not-so-invisible string, a cardboard moon rises, swinging doors slide into place in front of a waiting Blanchard. The orchestration is necessarily spare: a quartet perched above the action on a crowded riser done up as a bluff. Doo-wop, southwestern pop and lounge singing are set in arrangements that let the cast show off terrific pipes.

McLane belts from one number to the next. In fact, there’s not a dropped note in the show, and that’s an achievement because the spare production makes room for baroque lyrics. “It was us brought the murdering heathens to heel, bringing civilized ways to the West, and before I would allow anybody to steal what we fought for and died for my heart would have to lie cold as a stone in my chest” is a mouthful to sing, and that’s part of the joke. The full-tilt excesses of the 50s psychodrama are sent up in lyrics like “tell me the truth: tell me a lie” and “for being a tramp, she’s branded a tramp.”

If it’s all a little reductive and a lot silly, who cares? The tunes are toe-tappers, and the cast is having such a good time that the audience can’t help but enjoy themselves. Good thing the show has an open-ended run. On the night I saw it, Emma entered with her posse in the second act, and the audience spontaneously hissed. It was a hint that “Johnny Guitar” was becoming a cult classic all over again, this time on the stage.