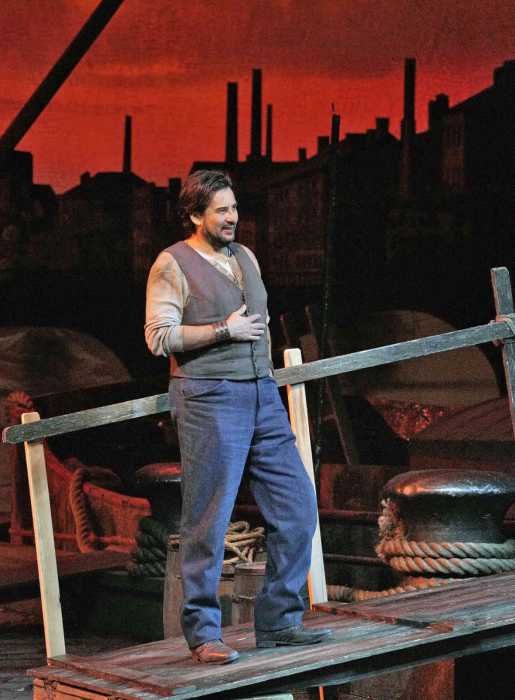

Piotr Beczala and Željko Lucic in Verdi's “Rigoletto.” | KEN HOWARD/ METROPOLITAN OPERA

Updated opera productions may be a recent phenomenon at the Metropolitan Opera but have been the norm worldwide for years. Michael Mayer (Broadway’s “Spring Awakening”) sets his new Met production of Verdi’s “Rigoletto” in “Oceans Eleven” Las Vegas circa 1960, where mob corruption and violence lurk behind the casino’s over-the-top showbiz glamour.

If this seems a bit familiar, Jonathan Miller did something quite similar at the English National Opera 30 years ago with his English-language production that reset “Rigoletto” in Mafia-controlled Little Italy in the 1950s. (Miller’s production traveled to New York in 1984 and was televised on PBS). Instead of the Duke as Mafia capo and jester Rigoletto a bartender, the Duke is now a Sinatra-style popular entertainer and casino owner and Rigoletto is an insult comic in the Don Rickles or Joey Bishop mold.

I have no problems with shifting the time and place of an opera as long as the director finds convincing contemporary analogues for the social mores and structures of the original story. In both Hugo’s original play and the Verdi/ Piave adaptation, the hunchback jester is a deformed lower class outsider in the aristocratic court. Both play and opera are about the abuses of power and how the lower classes can be used and then discarded by the rich and powerful.

Michael Mayer’s Vegas reset of “Rigoletto” offers both inventiveness and misfires

Making Rigoletto a Rat Pack insider and popular entertainer in his own right turns him into a near equal to the Duke — the social inequities central to the story are lost. This Rigoletto, dressed neatly in an argyle sweater and chinos with only a small hump and no limp or other deformity, is hardly repellent. Zeljko Lucic has an erect dignified posture and a glowering, introverted demeanor that further blurs the outline of the character.

Hugo and Verdi also contrast the disparity between the artificial glitter of the royal court and the bleakness and squalor of Rigoletto’s suburban house and Sparafucile’s seedy inn. Las Vegas is an excellent modern equivalent with urban decay and arid desert surrounding the neon glitz of the strip. Yet Mayer’s Rigoletto seems to have his own deluxe hotel suite with a private elevator (across the lobby from that of Count Ceprano, helping to facilitate Gilda’s abduction). Christine Jones’ sets, all acid colors and neon signs, create a world of surreal glamour that we never leave — even Sparafucile’s strip club in Act III is a neon dreamscape of “Showgirls” flashiness.

Mayer alternates many brilliant theatrical coups with glaring misfires. I loved the staging of Rigoletto’s first encounter with Sparafucile, which now occurs as part of the first scene. Sparafucile watches Monterone curse Rigoletto on the main casino floor. As the casino clears, Sparafucile buttonholes Rigoletto at the bar and offers his hit-man services while having a smoke and a drink. However, Monterone is turned into an Arab sheik complete with burnoose, adding potentially inflammatory religious and racial undertones.

Some of the business for the male chorus in Act I — miming shooting craps in unison — seemed more appropriate to “Sit Down, You’re Rocking the Boat” from “Guys and Dolls.” I like the stripper pole in Act III and the substitution of a vintage fin-tailed Chevy sedan’s trunk for the sack where Gilda’s corpse is dumped.

The Met titles are updated as well — “Cortigiani, vil razza dannata!” becomes “You and your pals are a bunch of dirty, rotten rats!” The audience laughed at some of the contemporary shtick in the staging and titles, which cuts both ways. It distanced them from the story, but on the other hand they were entertained and paying attention. Mayer isn’t being clever at the expense of the story, but sometimes his inventions backfire.

Musically, this is a high-level affair. Rising young Italian maestro Michele Mariotti led a propulsive, buoyant account of the score with clean articulation of strings and inner voices. Piotr Beczala has the blue eyes and swagger of a young Sinatra and the silvery tonal sheen of a young Gedda or Wunderlich. Some brash oversinging in the first act gave way to more finished elegance in the second and third acts. “Parmi veder le lagrime” was a highlight.

Diana Damrau, returning from maternity leave, now has a more womanly figure, but also a lusher, fuller, more womanly tone. The new vocal warmth and weight suited her Act II confession, “Tutte le feste al tempio,” but caused fleeting uncertainty in the exposed high coloratura of “Caro Nome.” Her commitment never wavered and her high E-flats are firmly there.

Å tefan Kocán’s Sparafucile, looking like Willem Dafoe as Bobby Peru, had a dead-eyed look and hollow bass that worked brilliantly. Oksana Volkova, in her debut, offered a muddy-sounding Maddalena — here a stripper-prostitute.

LuÄić’s Rigoletto remained distanced from the other characters and the distressing events of the story. His burly, imposing physique and voice didn’t connect fully with the heightened emotions — he evoked little pity, horror, disgust, or animal rage. It all seemed to be happening in his head but didn’t reach the audience. LuÄić’s is a genuine dramatic Verdi baritone, but the tone too often turned foggy, gray, and opaque where it needed to slice and thrust.

As for Mayer’s production, I found that the Vegas setting neither added nor detracted and the story and characters were recognizable in the new milieu. After it loses its novelty, however, I suspect audiences will lose interest. On the other hand, the Miller production celebrated its 12th revival at the ENO in 2009, so it’s all a roll of the dice.

“Rigoletto” will be transmitted in HD worldwide on February 16 at 12:55 p.m. EST.