John Edwards in tow, John Kerry heads home to claim prize

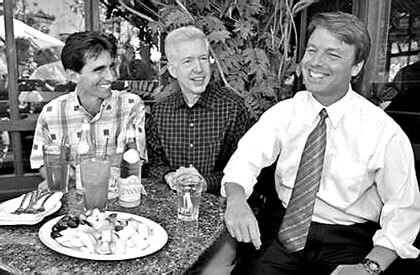

The day after then-California Gov. Gray Davis signed the state’s comprehensive gay domestic partnership legislation in a jubilant ceremony at San Francisco’s LGBT community center in September of last year, he stopped in the middle of the afternoon at the city’s Café Flor, a mainly gay outdoor café in San Francisco’s Castro District, to pose for pictures, talk to the television cameras, and appear with San Francisco’s gay assemblymember Mack Leno and an imported celebrity—the junior senator from North Carolina and presidential contender John Edwards.

The doomed governor had sent out an S.O.S. to the Democratic Party’s heavy-hitters to help him in his battle to survive recall, and Edwards had flown up from Los Angeles after a fund raiser there, partly to show party solidarity—but also because Davis’ perilous situation, some observed cynically, guaranteed him a trailing swarm of national and local TV crews.

“The governor was still glowing,” remembered said Leno, from the adulation of the bill signing the night before. The three sat together, on the warm Indian summer afternoon, and pretended to enjoy a stage-managed snack of fruit salad and bottled water.

Edwards was plainly uncomfortable. His starched white shirt and red tie stood out even in the crazy quilt of Saturday afternoon California casual attire, as he sat next to Davis and Leno, one of the state’s first two out gay male elected officials. Edwards’ rolled up sleeves signaled a ready-to-get-down-to-work attitude, while most of the crowd was taking the day off.

Seven months before, near the start of his presidential campaign at the California state Democratic convention, Edwards was the only candidate who hadn’t managed to weave some reference to gay rights into his stump speech.

Now, a few days after John Kerry chose him as his running mate, gays and lesbian organizations have embraced the ticket.

“The most gay-supportive national ticket in American history,” crowed National Gay and Lesbian Task Force leader Matt Foreman.

“Edwards solidifies the most pro-gay, pro-family ticket in the history of presidential politics,” wrote Dave Noble, the executive director of the National Stonewall Democrats.

But other activists offered a more nuanced assessment of Edwards.

“He’s totally new to our issues, and he started awkwardly,” said David Mixner, a former adviser to President Clinton who famously warred with the former president over the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy on gays in the military. “But he’s good looking, young, exciting and most importantly – he’s not Dick Cheney.”

Washington Post political reporter Evelyn Nieves pointed out that where Sen. John Kerry polls well, his good numbers don’t come from his own popularity, or from a strong personality, or from his stands on specific issues, but from a general disgust with Pres. George W. Bush, the state of the economy, and the war.

The Democrats’ “anybody but Bush” strategy now seems to apply, according to Mixner, to the vice presidential race as well as the race for the top job. To Mixner this is a good campaign strategy for the Democrats—not the lack of clear definition that some critics have charged.

“Here’s a president who has lied to take us into war, a V.P. who has been a profiteer from it, a man who has backed a constitutional amendment to permanently enshrine inequality in our Constitution, a man who wants to build logging roads through our national forests and drill for oil inside the Arctic Circle—would you compete with him for attention?” asked Mixner. An adviser with good access to the presidential candidate, Mixner promised that Kerry will be introducing himself to the American people in the four months remaining before the November election.

But even as Kerry works to continue to establish his image among American voters, it is Edwards who might bring the ticket its charisma.

“He connects,” Leno said, first with juries, in his previous and highly lucrative career as a trial lawyer and now with voters. “His eloquence is going to surprise, and he’s a very attractive candidate.”

Lesbian activist Carole Migden, chair of California’s tax oversight authority, described Edwards as “young and facile and articulate.” She also noted he will have no problem bringing in the votes of single women. Migden, who plans a November run for the state Senate, helped organize a Northern California benefit for him earlier this year and thinks he’s going to energize the ticket.

But, paradoxically, as North Carolina’s junior senator, Edwards was elected from the same state, by the same people, who elected Jesse Helms and returned him to office in the Senate for 30 years. In a close race in 1998, which was Edwards’ political debut, he upset incumbent Republican Senator Lauch Faircloth, a Helms protégé.

In his Senate race, gay rights were not a major issue.

“There’s a difference when you’re running from North Carolina versus when the constituency is national,” said Ethan Geto a long-time New York gay rights advocate and political consultant. Geto, who led Howard Dean’s New York campaign, says that as Edwards’ presidential campaign progressed, so too did his positions and thinking evolve.

“He has been more progressive than may have been practical,” Geto said.

Geto, who was a campaign manager for George McGovern in 1972 among many political postings, explained that the odd paradox, that Edwards could have been popular with the same people who also supported Helms, doesn’t speak so much to Edwards’ voting record, but to what Geto calls the importance of values as opposed to ideology.

“Edwards campaigned as a populist,” Geto said—and those values, the recurring themes of Edwards’ campaign, speak louder than his positions on specific issues. The son of a Robbins, North Carolina, mill worker, Edwards campaigned, in his soft Carolina drawl, on the theme of how the Republican Party has created “two Americas” one for the rich, and “one for the rest of us.”

And his trial lawyer background counts in the South, as credentials, a la Erin Brockovich, as a champion of the poor.

As his campaign progressed, Edwards came to understand the importance of the gay community in any potential victory. According to exit polls supplied by the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, five percent of the voters in a general election are gay, lesbian or bisexual and they vote overwhelmingly Democratic, at about 70 percent.

In February, just before San Francisco’s Mayor Gavin Newsom started marrying gays, Edwards was telling an MSNBC Hardball audience that he was “not for gay marriage. I am for partner benefits.” He has been consistently opposed to the Federal Marriage Amendment, stating his opposition as early as November of last year. He would repeal “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” and says he would not vote for the federal Defense of Marriage Act if it were to come to a vote today. In short, his position on most gay rights issues is almost indistinguishable from John Kerry’s—summed up in a statement he made about gays in the military: “What I’m for is treating everybody exactly the same, no matter what their sexual orientation…,” except when it comes to marriage.

Edwards spoke at a black-tie “gay soiree” dinner hosted by the Human Rights Campaign in Atlanta.

“It’s not like the guy’s got a lousy record,” said Geto, “it’s just that it’s not one of the big issues where he’s coming from.”

After a collegial call from Pres. George W. Bush, welcoming him to the race, the Republican National Committee was quick to blast Edwards. Some gay advocates took it as a testimonial that the RNC called Edwards the Senate’s “fourth most liberal member” quickly following Kerry as number one. The Republicans are trying to portray him as a rich trial lawyer who is driving up the cost of doing business in America. Democrats have countered the charge by calling him, as Leno did, “a self-made man,” as opposed to Bush “who everything he has going for him, he got coming from his father.”

As the Post’s Nieves points out, Kerry and Edwards could capture Washington without taking a single southern state. One (Yankee) political consultant described one of Edwards’ assets as the possibility he can help bring in what he glibly referred to as a few of the “country music states.”

Nieves also said that Edwards polls better with independents than any of the other former Democratic presidential contenders. The independents are the swing voters, Nieves said, and Edwards may draw in people who weren’t attracted to Kerry, because he’s dull, she said—“and Edwards isn’t dull at all.”