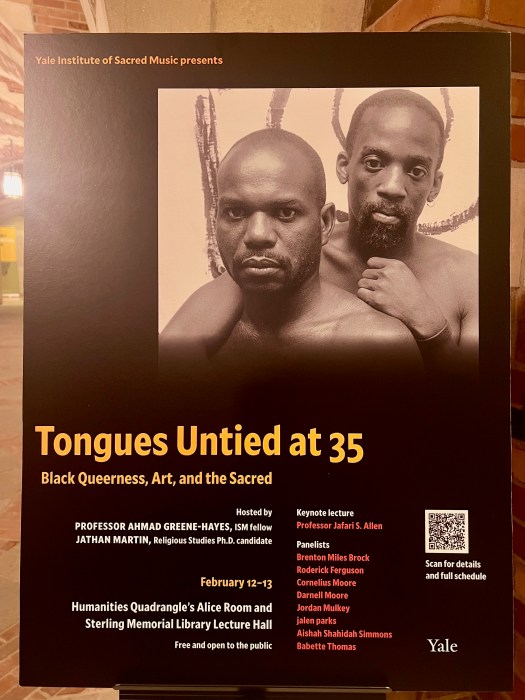

Associates, contemporaries, scholars, and students of the late filmmaker Marlon Riggs convened at Yale University for a two-day symposium, “Tongues Untied at 35: Black Queerness, Art, and the Sacred.” Riggs, who died in 1994 at the age of 37 from AIDS-related complications, directed and appeared in “Tongues Untied,” an experimental, semi-autobiographical documentary articulating the experiences of American Black gay men, released in 1989 amid the ravages of the AIDS epidemic during the Reagan-Bush era.

The symposium at Yale opened with a screening of “Tongues Untied,” followed by a panel discussion of experts who personally came to the film at different stages in their lives and careers, moderated by organizers Ahmad Greene-Hayes, a professor at Harvard University, and Jathan Martin, a doctoral student at Yale. The symposium proceeded the following day with workshops and a keynote address by Columbia University professor and author Jafari Allen.

Panelists connected the film’s central theme of resisting silencing to contemporary issues such as campus protests and the Trump administration’s imperatives.

“For me, it’s, ‘Does it speak to the moment?’” said panelist Aishah Shahidah Simmons, a filmmaker and writer. “And I feel like the film still — unfortunately in many ways, and fortunately in other ways — speaks to the moment we are in.”

With “Tongues Untied,” Riggs, based in San Francisco as a professor of journalism at Berkeley, aimed to, as he said, “shatter the nation’s brutalizing silence on matters of sexual and racial difference.” The film — the first of its kind in both content and form — immediately became a standard entry in college courses, academic conferences, and museum exhibitions.

Rare for independent films by directors from marginalized communities, “Tongues Untied” reached middle American audiences at the time of its release. But, not without considerable controversy. When the PBS documentary series, “POV,” selected and scheduled “Tongues Untied” to be nationally televised, it was met with furious objection from conservatives in Congress and the religious right, who condemned the film as “indecent and offensive.” A national debate erupted over government funding to art deemed “pornographic and blasphemous,” and a concerted effort to get the broadcast canceled was launched from Capitol Hill and the Bible Belt. Riggs doubled down, saying, “Implicit in the much overworked rhetoric about ‘community standards’ is the assumption of only one central community (patriarchal, heterosexual and usually white) and only one overarching cultural standard to which television programming must necessarily appeal.” PBS aired “Tongues Untied” on July 16, 1991, although some affiliate stations chose not to carry it.

In the ensuing decades, “Tongues Untied” amassed commendations, earning itself a place in the pantheon of US independent cinema. Most recently, in 2022, it was inducted into the National Film Registry, one of only 25 films per year the Library of Congress selects as “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.”

Panelist Cornelius Moore, former director of the film distribution company California Newsreel who was a friend and colleague of Marlon Riggs and himself appears in “Tongues Untied,” recounted the backstory of Riggs’ conception of the film in 1988.

“I want to do this short, experimental film about Black gay male identity,” Moore recounted Riggs telling him. “Shortly thereafter…he found out that he was HIV-positive. It transformed this film, this idea, to be more than a short, into a feature-length film, experimental but also involving him in a personal way, and involving people in the community.”

The film features Black gay men who Riggs knew through activist, artistic, and social groups and spaces, men such as the actor Brian Freeman of the theater collective, “Pomo Afro Homos,” activist and writer Colin Robinson, and most prominently, poet Essex Hemphill, who recites his poetry throughout the film, among many other collaborators.

“No question at all that Marlon is the auteur of this film,” Moore said. “But, he involved other people who had their own artistic practices — poets, musicians, actors — and other people from around the country — activists in D.C., in New York.”

The result is an amalgam, as panelist Darnell L. Moore, a Lambda Literary Award-winning author and 2019 Gay City News Impact Award honoree, described it, of different documentary styles and artistic expressions, of dramatization, dance, spoken word, song, newsreel, drawing and still photography, all overlaying one another.

“The form of the film itself is a queer material manifestation of what Riggs is trying to get us to ideologically think about, which is to query the boxes, get out of the boxes,” said Darnell Moore. “It is ethnography, it is autoethnography, it is performance, it’s all those things in one.”

Among the many sequences in the film that typify this aesthetic of layering, one strikingly begins on the east coast and concludes on the west, drawing attention to the cross-country conversations and engagements among Black gay men Riggs encouraged. The scene opens with footage shot on New York’s Christopher Street piers, at the time a meeting place for Black and Latino gay men and trans women. It is a summer night and the camera captures the artistry of vogueing as performed by masters of the dance form, among them Willi Ninja. The original audio is replaced with a voiceover of Essex Hemphill reciting his poem, “In the Life,” with the instrumental Chicago House-music track, “The Poke,” by DJ Adonis in the background. The scene eventually fades to daytime footage of Riggs and friends dancing in a park in San Francisco with his own voice overlain.

“I first watched ‘Tongues Untied’ in my college dorm room at Howard University,” said panelist Roderick A. Ferguson, a professor of gender and sexuality studies at Yale University. Ferguson recounted how he proceeded to come in contact with individuals and institutions connected to the film in one way or another, profoundly impacting the course of his career. He still includes the film in courses he teaches.

“You find yourself in formations that you were always meant to be in,” he said. “That’s what it is for me to watch and teach this film: the discovery that what I thought was an accidental encounter in my dorm room via PBS was actually part of a greater plan.”

Nicholas Boston, Ph.D., is a professor of media sociology at the City University of New York-Lehman College