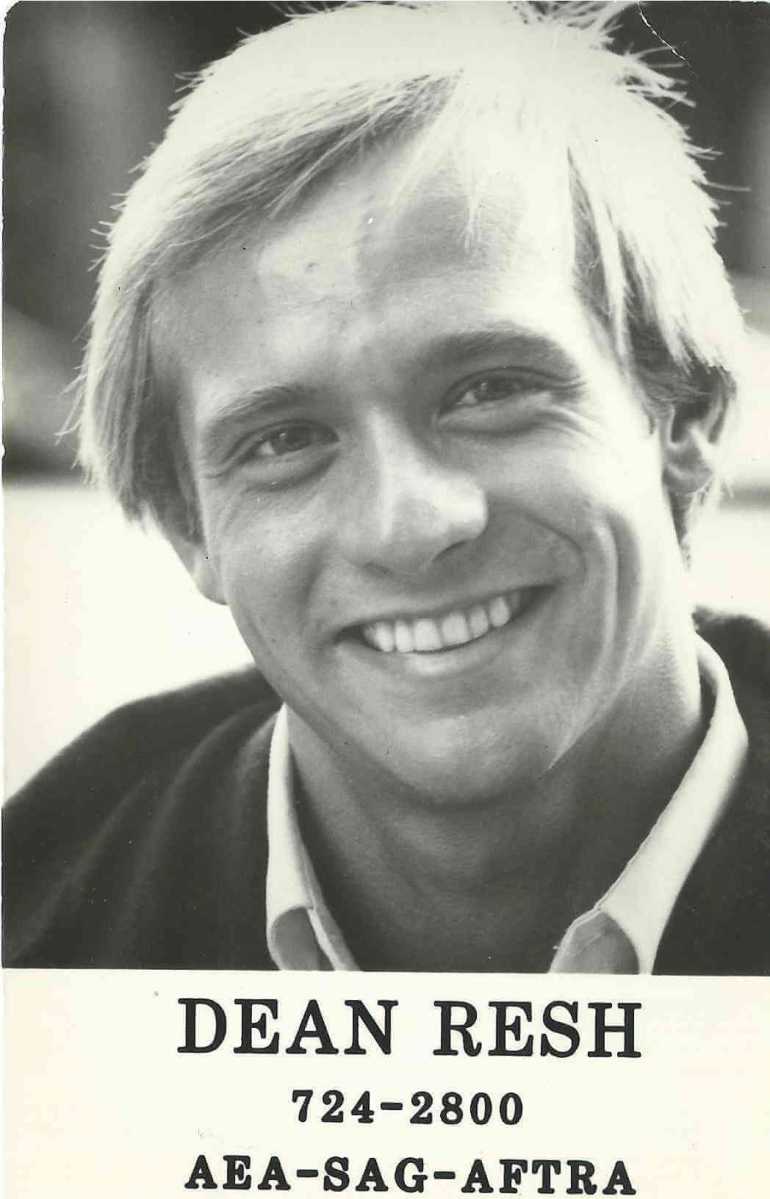

I yelled, I screamed, and after punching pillows to exhaustion, I slumped down into the empty chair next to me in tears.

It was the mid-’80s; Gestalt therapy was big.

My therapist took in a deep breath, leaned back in his chair, and crossed his legs.

“Congratulations! You had a breakthrough today.”

I lifted my head from the beaten pillow and laughed. “I think you mean breakdown.”

“Not at all! You finally admitted you have been resenting your mother and sister for stopping you from coming out to your father.”

It had been more than a year since that phone call when I fought with them about coming out to my dad by bringing my boyfriend, Allen, home for Christmas.

“Jesus Christ, Dean,” my mom said. “Do you want your father to have another stroke?”

I heard the voice of my sister Vicky rise in the background. “Let me talk to him!” I was about to get tag-teamed.

“I can’t believe you!” she said.

“Are you telling me even you don’t get it? You, of all people?”

“This isn’t about me. It’s about you thinking only about yourself. It’s just selfish.”

“Does he know about you and your girlfriend?” I asked her.

“No, he doesn’t, and I don’t need him to.”

Only a few months would pass before my sister’s girlfriend would sit down with my mom and make the announcement herself: “Vicky and I are lovers.”

After that bombshell delivery, I was told my mom got up, grabbed a broom, and started sweeping the front porch as she muttered, “Jesus Christ, now I’ve got two of ‘em.”

When my sister returned the phone to my mother, I said, “Okay, you guys win. Here’s the deal. If Allen can’t come, then I’m not coming home for Christmas. I will not have the man I live with and love be alone during the holidays.”

That was the first year I did not open presents with my parents. Allen and I stayed in New York, bought a tree too large for our studio apartment, decorated it with a few sets of string lights, and scattered it with red bows we made from a spool of felt ribbon. We made our own Christmas together.

We broke up more than a year later. Although he was gone, the need to tell my dad about myself was still present. And by coincidence, I thought that television could do the job for me. I called my mom.

“I want to speak with Dad,” I told her.

“Al, your son wants to talk to you!”

“Dean?” He sounded cheerful.

“Dad, there’s a really good movie on tonight.”

“Yeah, I know! Dirty Dozen II. Can’t wait!”

I looked at the newspaper’s TV listings to check for myself. A made-for-TV sequel of the 1967 film was playing on another channel at the same time. Stiff competition. How could I ask my dad, a World War II fanatic — not to mention a veteran of that war — to forego a film about an attempt to assassinate Hitler? But I went for it.

“Actually, it’s another movie I had in mind. It’s called ‘Consenting Adult,’ and it’s a special film. It would mean a lot to me if you watched it.”

Then I let it go.

My mom called me the next day.

“Your father and I watched that movie,” she said to me. I was more than surprised.

“Well?”

“Well, sometime after Martin Sheen died of a heart attack and Marlo Thomas told her son that she loved him, I looked at your father and said, ‘You know, Dean’s that way. Gay.’”

“What did he say?”

“He said, ‘Ya know, I thought he might be. When he said he was moving to New York to be an actor, I thought that it was also partly to find himself.’“

I was struck by my mom’s forthcoming description of his reaction, considering her certainty of his having a conniption. But it was consistent with my dad’s live-and-let-live belief system. She had only projected her hang-ups about homosexuality onto him. No strokes, no heart attacks, no wondering about where he had gone wrong. Most importantly, total acceptance.

The next time I was home visiting, Dad and I were watching an old black-and-white movie starring Marilyn Monroe.

“Dean, let me ask you something. Are you saying that [pointing to her curvaceous beauty] doesn’t do anything for you?”

I laughed. His inquiry was genuine; his innocence, disarming.

“Let me put it this way. I appreciate she’s a beautiful woman. I mean, I’m not blind. But no, she doesn’t excite me the way you are talking about.”

“Huh.”

Later, we were watching a Wimbledon match together. He was a big fan.

“Go, Martina! Go, Martina!” he shouted at the screen.

I turned to him and said, “You do know, dad, that she’s a total lesbian.”

Without skipping a beat, his eyes darted at me for a nanosecond only to reply, “She can’t help it!” He turned back to the game and reprised his chant. “Go, Martina! Go, Martina!

A smile ran across my heart as I shouted, “Go, Martina! Go, Martina!”