This Met season has Jules Massenet’s “Manon” near its start and Puccini’s “Manon Lescaut” near its close. Both are major works but very different in their treatment of the Abbé Prévost novel and its leading pair of reckless teenage lovers.

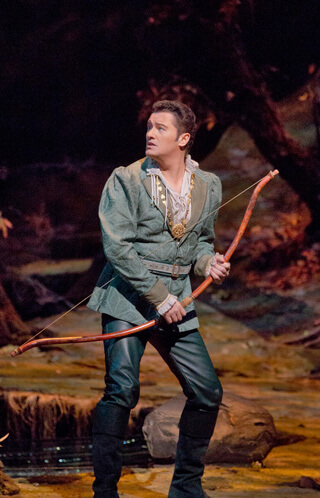

At September 24’s revival premiere, we had promising and in many ways exciting casting in the first-ever Manon of the increasingly expert Lisette Oropesa and the first des Grieux of out gay Michael Fabiano, who tried “Manon” out in Bilbao last year. The soprano looked Manon to perfection, both as a randy hayseed and a sophisticated cocotte; her voice, clear and attractive if without an intensely personal timbre, took a while to unfurl, but except for a few topmost notes she had everything well in hand technically and showed a fine command of Gallic style. The tenor — admirably out for a performer of leading romantic roles — offered a lot of highly charged Italianate tone, sometimes to a fault a la late period Giuseppe di Stefano. While he also managed to sing softly in a wistful “Reve,” it only rarely sounded like true voix mixte. Energy Fabiano had — he played the aristocratic would-be seminarian like a handsy horndog. These two performances didn’t quite blend but both had much to offer.

Management mysteriously conferred this perfumed, tuneful score to Maurizio Benini, far from his usual repertory and (alas) sounding it. Tempi were slack and several major concerted numbers threatened to falter. There was not plainly enough rehearsal and the ensemble will improve. As with “Lulu,” I always feel that the “Manon” gambling scene could be excised with little detriment. It offers about four minutes of worthwhile music: des Grieux’s repeated “sirène” addresses to Manon — which strained Fabiano to his limits — and the trio, where Oropesa finally managed a clean, stunning D.

We heard good spoken and sung French from Oropesa but the cast contained not a single native francophone. Artur Rucinski’s Lescaut gave further evidence of his fine baritone and adaptable stage presence; his elegant “O Rosalinde” was a true highlight. The finely vocalized Bretigny of another out gay artist, Canadian baritone Brett Polegato, marked an overdue Met debut, after having come to New York City Opera 15 years ago. It’s important (and rare) to have an accomplished singer in this crucial part. Kwangchul Youn acted a suitably magisterial and arrogant Comte, but though his bass retains its heft and appealing warmth it now has a pronounced wobble. Debutante Jacqueline Echols sounded appealing as Poussette, the part that brought Teresa Stratas to the Met in 1959.

Director Laurent Pelly’s seemingly Cecil Beaton-inspired costumes lent color to the show. I’d forgotten that Chantal Thomas’ wan sets and props look like they’d been acquired at IKEA for $800. It still makes zero sense to have des Grieux sleeping on a bed in the St. Sulpice church, though it does add spice to the seduction scene. Despite some shortcomings this “Manon” showcased some fine singing and acting; worth seeing or catching at October 26’s HD showing.

October 1 brought the third performance of one of Verdi’s most enjoyable operas, “Macbeth”. Each performance had a varied leading couple, as at the previous performance Craig Colclough had stepped in for Zeljko Lucic as Macbeth and this evening marked the Met debut of a much-talked about Italian soprano, Anna Pirozzi, stepping into the part superstar Anna Netrebko took at the other shows.

When the Met first mounted “Macbeth” in 1959, the terrifyingly written Lady Macbeth served as Leonie Rysanek’s triumphant debut vehicle, launching a 37-year company career (though her local Verdi excursions ceased in 1964). Only two others have dared the challenge as a company debut: the fearless Olivia Stapp (1982) and the disastrous Nadja Michael (2012), one of the current regime’s most notorious “Looks 9/ Voice 2” passing enthusiasms.

The Neapolitan Pirozzi, billed as a dramatic soprano, has sung the role in several major European centers including London, Paris, and Madrid. She sings other voice-risking Verdi parts in “Nabucco” and “Attila,” plus Puccini’s “Turandot.” This seems like playing with fire. She showed stage confidence and — if not quite Netrebko’s remarkable charisma — real presence, plus genuine Italian diction and a house-filling Verdian dramatic spinto. She did very well indeed for most of the evening, winning several ovations, before tiring in the final hurdle of the Sleepwalking Scene’s thread-of-voice high D flat. The voice, remarkably even, has bite and spin; she tended to vary dynamics rather than vocal coloration. I’d love to hear her as some of the less acrobatic Verdi heroines, like Amelia Grimaldi and Elisabetta di Valois.

Lucic sang with considerable caution, thus giving a more nuanced and on-pitch performance than I’ve heard from him in some years. Ildar Abdrazakov isn’t the rolling Jerome Hines/ Nicolai Ghiaurov bass Banquo needs but he knows his way around Verdi (and the stage). Through his trademark layered dynamics and tapered phrasing, Matthew Polenzani made a moving success of Macduff, his heaviest Met part yet. He and Giuseppe Filianoti’s Malcolm made their duo tenorial interaction far more musical than usual. Good to see the compelling Calabrian tenor back after six years; one hopes the Met utilizes his talents imaginatively. We heard capable work in supporting roles: Sarah Cambidge (Lady-in-Waiting), Harold Wilson (Physician), Richard Bernstein (Murderer), and Christopher Job (Warrior).

Unlike with “Manon” and “Porgy and Bess” we had a conductor versed in the proper idiom, Marco Armiliato. But — even though chorus and orchestra performed well — he brought little animation to Verdi’s wonderful score.

Sometimes it’s salutary to leave behind Lincoln Center and Carnegie Hall and head to the city’s smaller troupes and venues. These can offer more radical interpretations or, alternatively, a connection to old-fashioned operatic values, like the bedrock “red sauce” italianness that long defined the genre for many patrons.

On September 28, I took a brief train ride and hike to Our Lady of Mercy Church in Forest Hills, Queens, where the Golden Rose Opera presented a one-off “Madama Butterfly.” It proved a worthwhile trip thanks to the professionalism, stylistic groundedness, and focus of the leading couple, Sabrina Palladino and Paolo Buffagni.

The soprano — looking like a 1940s movie star and acting every moment with grace and subtlety — fully commands the verismo idiom in a way we haven’t heard locally in this opera since Diana Soviero retired her kimono. She paced herself well and was able to float all but a few testing climaxes. Like my first-ever Cio-Cio-San, Patricia Craig (who learned it from Magda Olivero), Palladino can channel the art of flipping into an expressive high pianissimo that carries. Her remarkable performance got good support from Buffagni, a veteran of small local companies who can still at least suggest youthful ardor and fill out — with, again, occasionally spreading top notes — the contours of a surging Puccini line. Though his voice lacked smoothness, Gustavo Morales (Sharpless) also made the text and his role in the drama admirably clear.

It’s great that older and younger people could pay $20 to enjoy the essence of “Madama Butterfly” with an idiomatic leading trio. Given that there was only one rehearsal, quite a bit came across. Helen Van Tine-Golden, whose enterprise made this all happen, gave a knowing, committed performance as Suzuki, while Puccini’s music might have been better served by deploying the sensitive Kate, Kayla Faccilongo.

As director, Van Tine-Golden brought on nearly the whole cast for what’s meant to be Butterfly’s lonely suicide. There was no chorus, so either Goro and Suzuki handled their contributions or a synthesizer did, which worked quite well for the Humming Chorus. Act Three’s prelude went missing. Despite some good instrumentalists on hand in the chamber group, Alex Wen’s conducting was often muddled and dragging; at times things nearly fell apart. That Palladino withal kept her focus and characterization in this long, difficult part speaks wonders for her.

David Shengold (shengold@yahoo.com) writes about opera for many venues.