Most of the songs performed were by or about women. Four Black women were represented as composers (two utilized texts by gay men, Walt Whitman and Langston Hughes). Bryce-Davis had premièred Melissa Dunphy’s Whitman-based “Come, my Tan-Faced Children” in 2019; she offered two affecting, affirmational songs by Maria Thompson Corley, present in the hall: “The Beauty in my Blackness” (a world première, exciting) and “I’m Not an Angry Black Woman.” Unlike many performers with large voices, Bryce-Davis was able to make her words clear and her vocal attacks clean in this auditorium’s intimate space. Despite the richness of her tone, she communicated the English and German texts with point and (where needed, as in three wonderfully varied folk song stylizations by Jamaican composer Peter Ashbourne) relish. Most effective of the German selections was Brahms’ “Von ewiger Liebe,” which has a narrator, a male persona, and a female persona — who gets the final word. Both musicians gave a lot during this recital, and they ended it powerfully with “Don’t Feel No Ways Tired” in Jacqueline Hairston’s arrangement.

On October 16, the New York Festival of Song presented a stirring concert in the intimate cabaret-like space of the Rubin Museum’s theater/café devoted to the vibrant songs of Errollyn Wallen (b.1958). The Belize-born, UK-dwelling composer transcends boundaries of genre, her pithily structured and evocatively crafted songs reminding one at different times of Joni Mitchell, Joan Armatrading and Alec Wilder. I’m glad I read the subtle lyrics in advance, since the venue turned the lights way too low; and fortunately the two vocalists on hand — Lucia Bradford and Leah Wool — are both exemplary purveyors of clear, meaningful textual phrasing.

Both mezzos have substantial professional credits, but deserve wider renown. Bradford boasts a soulful, wide-ranging instrument with an awe-inspiring lower register, capably of bluesy coloration and inspired improvisatory scat effects. By contrast, Wool’s high lyric mezzo offers the tonal clarity one wants but rarely hears nowadays in music theater material. Both artists command the art of meaningful phrasing and, with the nimble and gifted pianist/curator Nathaniel LaNasa, brought 11 Wallen numbers — every one worth hearing and contemplating — to vivid life. La Nasa made an earnest, enthusiastic host, but (from my perhaps jaded-sounding Manhattanite perspective) should refrain from telling his listeners how great and special his singers are. That’s ours to decide, and in the case of Bradford and Wool, their stellar work makes their excellence obvious. Bradford returns for NYFOS’ founder Steven Blier’s 50th anniversary onstage, a February 15 Merkin Hall concert entitled “Amor.”

October 19’s “Tosca” at the Metropolitan was a pleasing repertory performance of the basically pictorial, unchallenging production by David McVicar. What made the evening interesting — despite Carlo Rizzi’s plodding, over-deliberate conducting — was the stage chemistry of the romantic leads, Aleksandra Kurzak, and Michael Fabiano. Surely the most visually plausible Tosca/Cavaradossi pairing hereabouts since 2010’s Patricia Racette and Jonas Kaufmann, they achieved a detailed, credible partnership that made the personal drama more involving. (Appearance can be overstressed in opera today, but many school groups were in attendance and “relatability” counts for much for visually oriented people new to the form.) The Polish soprano continues her successful career trajectory from high coloratura to full lyric soprano roles. While not a high-decibel Tosca, every phrase received its musical and dramatic due. She produced chest tone when appropriate and she had an uncommonly easy time with the parts upmost reaches.

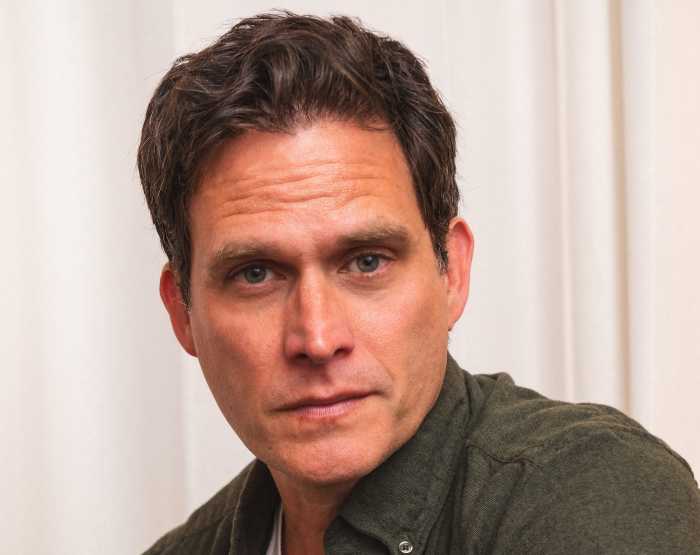

The last can’t quite be said for New Jersey’s Fabiano — he sometimes forced a bit, and slightly flattened the high Bs — but in general was in relaxed control of his high-quality instrument, giving a well-considered idiomatic performance. It’s rare to have even one openly gay male singer who’s not a countertenor or a lyric “barihunk” onstage but here we had three: Fabiano, the resonant-voiced Patrick Carfizzi (Sacristan, funny but milking a few too many “public pet” moments), and Rodell Rosel. George Gagnidze, in fresher form this season, made a highly satisfactory Scarpia.

The next evening at Columbia University’s valuably intimate Miller Theater series, another audience rich in students heard an all-Bach concert curated by pianist/conductor Simone Dinnerstein. I’ve never understood her considerable acclaim among the NPR/New York Times/tote bag set, and her fluent but foursquare pianism in the E major Keyboard Concerto here did not change my mind. But the guest artists of her rather scrappy Ensemble Baroklyn earned deserved applause for the evening’s prime offerings, two Bach cantatas. Out and proud countertenor Reginald Mobley, who’s forged a substantive international career in baroque and contemporary music, brought his sonorous, fluid voice and stylistic acumen to “Widerstehe doch der Sünde” and the inevitable (because so transcendently beautiful) “Ich habe genug.” Mobley’s caressing voice proved even freer, and the ensemble’s string tone more pleasing, in the second, post-intermission cantata, when joined by stellar oboist Peggy Pearson.

It was good to have Britten’ terrific “Peter Grimes” back at the Met October 26, even in a musically merely solid reading led by Nicholas Carter. Sadly, the misguided direction (John Doyle) and perversely cramped set (Scott Pask) kept the performance from catching fire. Plus, Doyle and leading man Allan Clayton (fresh if monochrome of voice, with admirable diction throughout) seemed uninterested in exploring the opera’s stratum of forbidden homoerotic desire fueling the Borough’s exclusion of Grimes. Clayton eschewed the show-offy weirdness he brought to Hamlet and achieved some intensity. Nicole Car made a sympathetic Ellen, with a shining top, but — like many fine Ellens before her, including such great sopranos as Elisabeth Soederstroem and Renée Fleming — lacked the middle register strength to dominate the second act ensembles, in which Wagner’s Elsa seems to be Britten’s model. Czech baritone Adam Plachetka — to me an inexplicably prominent presence at the company — fared better with Balstrode’s English than anticipated; the timbre is undistinguished but he was at least adequate.

Happily, feisty contralto Margaret Gawrysiak made a very solid, legato-based emergency debut as Auntie, replacing an iconic artist whose patchy current vocal resources would scarcely allow success in the part. The ensemble was quite strong, with tenors Chad Shelton (Bob Boles) and Tony Stevenson (Reverend Adams) the standouts alongside Justin Austin’s aptly dishy Ned Keene. This great opera deserves a new production fast.