Uptown restaurant files suit vs. statute used to shutter bars, video stores

BY DUNCAN OSBORNE | In what may be the first such challenge, a restaurant temporarily shuttered under New York City’s nuisance abatement law has asked a state court to strike down the law and has filed a federal lawsuit that also seeks to have the law declared unconstitutional.

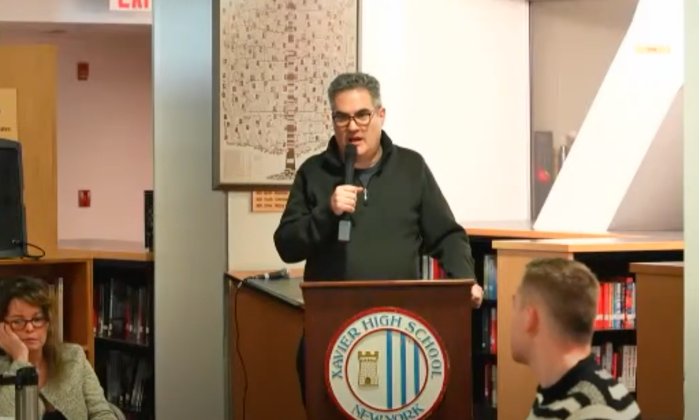

“The law was written to combat illegal establishments,” said Kevin B. Faga, an attorney at Faga Savino, LLP, a White Plains law firm. “It’s not meant to be applied to legal businesses that commit the occasional violation.”

Faga represents Tokyo Pop, LLC, which owns the location at 2728 Broadway, and Papasito Midtown Corp., Inc., which operates the Papasito Mexican Grill and Agave Bar there.

Following complaints from the community about noise, excessive drinking, and fighting at the restaurant, the police department sent undercover detectives with underage auxiliary officers into the restaurant. The auxiliary officers were served alcohol three times in late 2011 and once in January of this year.

The police department cited those four instances, which are still unproved, and obtained a temporary restraining order under the city’s nuisance abatement law that allowed the city to close the restaurant for three business days. In court filings, the restaurant said the temporary closing cost it about $30,000 in lost revenues. The city wants to close the business for one year.

In state court filings, the businesses asserted that New York’s Alcoholic Beverage Control Law governs the operation of establishments that are licensed to sell alcohol and that statute preempts the city law. In its federal filing, the businesses said the nuisance abatement law “violates the Plaintiffs’ due process rights as it seeks to deprive them of property based on violations that the alleged offenders have neither admitted nor been adjudged to have committed.”

The city has used the nuisance abatement law to close nightclubs and bars, including gay bars, bathhouses and sex clubs, porn shops, gambling dens, chop shops, and retail locations that sell counterfeit goods. The nuisance abatement actions are civil lawsuits, not criminal actions.

In 2008, police made a series of prostitution arrests of gay and bisexual men in Manhattan porn shops and spas, then sued those businesses under the nuisance abatement law charging they were allowing prostitution. When Robert Pinter, one of the men who were arrested, went public, police stopped the operations and tacitly conceded the arrests were flawed.

The city’s nuisance abatement law was enacted in 1977. It was meant to target businesses where illegal activities were going on.

“The concept of the nuisance abatement law was to give the police or the corporation counsel… a way to get an order to close the premises if indeed there were illegal activities going on in the place,” said Sidney Baumgarten, an attorney now in private practice who wrote the law, in a 2009 interview.

Baumgarten headed the Midtown Enforcement Project, now the Mayor’s Office of Special Enforcement, from 1974 to 1978.

“We were very careful because we said you cannot use the nuisance abatement law… unless you can come in and show there were actual convictions,” Baumgarten said.

The law has been amended since 1977 to make it easier to bring cases. Police can cite arrests or the “common fame and general reputation” of the location.

Police will present the arrests and any other evidence to a judge without informing the targeted business to get the three-day temporary closing order. Gay City News has found less than a handful of cases in which judges denied such an order. The city then closes the business and only then can the owner contest the allegations. Most businesses either abandon the location or settle with the city quickly to avoid further economic harm.

The law’s use exploded after the police department created its own legal unit in 1991. In a 1999 book, “NYPD Battles Crime: Innovative Strategies in Policing,” author Eli B. Silverman reported that police filed 214 nuisance abatement cases in 1994, and that number climbed to 709 in 1996 and 712 in 1997.

Police brought 899 nuisance cases in 2008, 639 in 2009, 901 in 2010, and 991 in 2011. In the 2009 interview, Baumgarten whistled in shock at the 2008 number and said, “It tells me it’s probably being abused.”

The city’s Law Department did not respond to an email seeking comment.