Susanna Phillips and Christopher Maltman in the new Jeremy Sams production of Johann Strauss, Jr.'s “Die Fledermaus” at the Met. | KEN HOWARD/ METROPOLITAN OPERA

Under the Gelb administration, the Metropolitan Opera has employed its New Year’s Eve Gala as a vehicle to unveil new productions. To ring in 2014, the Met relied on a traditional standby –– Johann Strauss, Jr.’s operetta “Die Fledermaus” –– pitching yet another Otto Schenk/ Günther Schneider-Siemssen production onto the scrap heap in favor of one from Jeremy Sams, with sets and costumes by Robert Jones. Sams translated the sung German lyrics into English while Broadway playwright Douglas Carter Beane reworked the dialogue scenes.

Operetta is a difficult proposition in large opera houses –– opera singers are not trained to deliver stylish light comedy dialogue or project witty lyrics clearly. Then there is the question of translation with its inherent compromises. European comedy of the 19th century is very different from American comedy of the 21st century. Do you update –– and if you do, how? Charm is an outmoded concept.

Jeremy Sams’ “Die Fledermaus” production time-shifts uncomfortably

In 1950, Rudolf Bing went the Broadway route, bringing in Garson Kanin to direct and redo the book while Howard Dietz provided English lyrics. Audiences flocked to it despite the critics. The 1986 Schenk/ Schneider-Siemssen production attempted a return to authenticity with a hybrid of the original German sung lyrics and the dialogue in English. It proved ornately handsome but stiff and lifeless from the beginning –– Comden and Green’s revamped book in later revivals didn’t help matters.

Jeremy Sams goes for fin-de-siècle decadence by pushing the time period forward 25 years to December 31, 1899 and the dawn of a new century. This is not a bad concept, but for every excellent idea Sams and Beane came up with there are two that miss the point. By pushing too hard for cleverness, several jokes grate and a few offend. Sams alternates witty couplets with forced and twee doggerel.

Gabriel von Eisenstein is turned into an assimilated Jew with a menorah on the piano and dialogue peppered with words like schlemiel and mensch. But then in Act II, there are toasts to the new century ironically predicting Austria achieving a century of peace and social order. Prince Orlofsky prophesies that the 20th century will be good for the czar and his family. Rosalinde introduces her Czárdás by lamenting Germany’s annexation of Hungary. It leaves a sour taste that kills the champagne buzz. Contemporary pop-culture references to Barbra Streisand, Sondheim songs, and pedophile priests are thrown in, which get easy laughs but pull you out of the period.

The original Genée and Haffner libretto has witty situations and essential dramatic exposition that are brushed aside by all this folderol. The new production’s team just don’t know when to leave well enough alone. Robert Jones’ sets stylishly evoke the Jugendstil art movement, with Klimt-style paintings decorating the Eisensteins’ drawing room. His costumes, however, lack the same carefully chosen palette and elegant line; the gowns look garish, heavy, and shapeless. Stephen Mear’s choreography looked a little too Weimar “Cabaret” era meets Vegas “Showgirls” and was underrehearsed.

Rising tenor Michael Fabiano as Alfred proved equally brilliant as actor and singer. He has real comic timing and his impromptu tenorizings were balm to the ear while tickling the funny bone. Broadway’s Danny Burstein as the drunken jailer Frosch proved an artful comedian, putting over uneven material in his Act III opening stand-up comedy monologue.

The rest of the cast was a mixed bag. Susanna Phillips as Rosalinde projected wholesome American “diva next door” charm and her middle range is luscious. But her upper register turned ragged in the trio that ended Act I and she left out florid high phrases and low ones in her Act II Czárdás. She also made several musical entrances late.

Baritone Christopher Maltman initially was a suave Eisenstein but struggled with the high tessitura (it is often cast with a tenor) and by Act III he was shouting his high notes. Paulo Szot as Dr. Falke was blusteringly cheery throughout, lacking the necessary cool Machiavellian guile. His rough and ready baritone failed to negotiate a smooth soft line in his Act II “Brüderlein und Schwesterlein” serenade. Jane Archibald as Adele won applause for her brilliant staccati in the Act III audition aria. Yet she seemed an ingénue in a soubrette role, lacking pertness and sparkle.

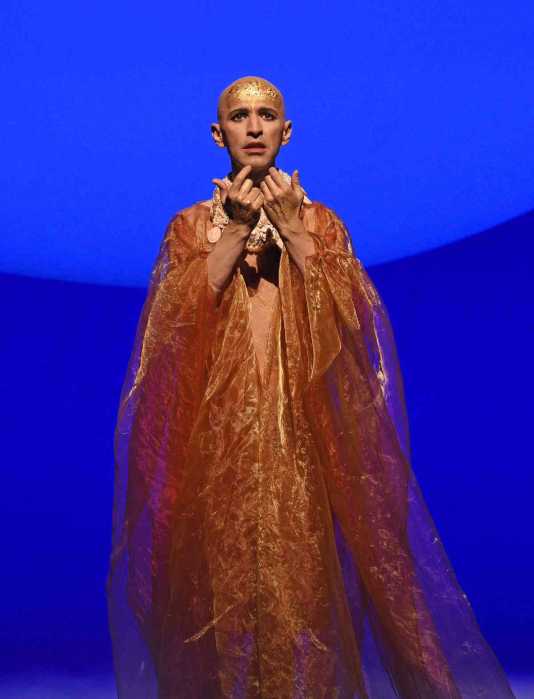

Anthony Roth Costanzo’s appealingly dizzy, extravagant, and eccentric Prince Orlofsky looked like a combination of ’80s pop singer Prince and Liberace. But the role is awkwardly written for a mezzo and even more so for a countertenor. Costanzo seems to be singing around the wrong register breaks and his high notes were screechy –– a little artful transposition and vocal rewriting would have helped here. Broadway refugee Betsy Wolfe as Ida got stuck with a lot of Beane’s worst lines while Patrick Carfizzi was a capable if rather unimposing Frank.

The Hungarian maestro Adam Fischer has a knowing way with the music but it was all too neat and contained –– the essential dash and esprit were missing in action. Despite the gala occasion, there were no surprise guests in Act II.

Still, with all its missteps, there is a light-on-its-feet energy and verve in this staging that were missing from the previous production. A little judicious editing of the book and lyrics, some costume alterations, a better cast, and zippier conducting could turn this into a very good show.