With movie theaters still closed and many people sitting at home with time to kill, streaming services have benefited. It’s not hard to find lists of recommendations for films and TV shows on Netflix, Amazon, Hulu, or HBO Max.

MUBI is something different. Its original concept offered a carefully curated selection of 30 films, with a new movie premiering every day. However, the titles were only available for a month (although a few could later be rented through the site itself or Amazon Prime.) MUBI has eclectic taste — you can find classic films from the 1920s by gay director F. W. Murnau, recent movies that played international festivals but have not graced American theaters, Bollywood landmarks, offerings from the indie gross-out horror studio Troma, and retrospectives on directors like Angela Schanelec, Heinz Emigholz, and Philippe Garrel.

Under COVID lockdown, the concept behind MUBI has changed, as it has opened up its library, making a selection of hundreds of films available to subscribers. A monthly subscription cost $10.98, while one can buy a year in advance for $95.88. Seven-day free trials are available. It would be impossible to sum up all the LGBTQ-themed films in a fairly brief article, so I chose four very different titles.

Pia Hellenthal’s “Looking for Eva” made me feel very old. Its subject, 25-year-old Eva Collé, is a non-binary sex worker, fashion model, social media celebrity, poet, and musician (among other things) who documents their life with numerous selfies. “Searching Eva” feels more like new media than a film, especially in its tone of carefully poised, faux-casual oversharing. It’s hard to tell where Eva’s healthy desire to tell the truth about their body bleeds into a selfie-driven narcissism. Does even seeing this distinction just show my difference from their generation?

Produced by Vice Studios, “Searching Eva” shows signs of their brand of woke sensationalism: It depicts Eva fully nude, having sex, and, though she describes herself as a recovering addict, preparing to shoot up drugs. But if it starts out feeling like a string of disconnected scenes, the combination of images, onscreen text, and voice-over amount to a telling character study.

Eva’s present life choices are influenced by a desire to escape the repressive and sexist Italian small town where they grew up, the fact that their parents were heroin addicts who became born-again Christians when they quit drugs, and the poverty they’ve experienced. Despite the apparent glamour of their current life, one intertitle reads, “I get more money for a blowjob than 3 days paris fashion week.” More than the story of just one person, “Searching Eva” profiles a way of life where boundaries between private and public – and, probably, fiction and truth — have become terminally uncool, but the pain of trying to make a living and get by in a sexist and queerphobic word persists.

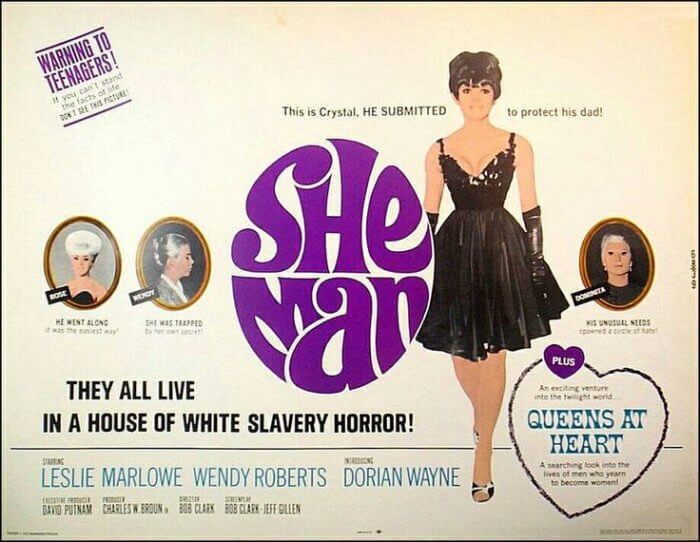

To get the obvious out of the way, Bob Clark’s 1967 “She-Man: A Story of Fixation” is objectionable in many respects and has nothing to do with the reality of trans women’s lives. But it’s also revealing about its times. Exploitation films have often been bluntly honest about topics more “respectable” fare does not even hint at: In this case, the fantasies of a man who want to be dominated by trans women. Clark would later make classic films like “Black Christmas” and “A Christmas Story,” and his talent was already evident here, especially in the exquisite film noir-inspired use of shadow and darkness.

Korean War vet Albert Rose is blackmailed by Dominita, a trans woma who kidnaps him and forces him to dress in drag and take estrogen pills while working as her maid for a year. Technically, he may be the film’s hero while she’s the villain, but he’s a bland wimp while she’s a charismatic bad-ass. That doesn’t excuse the film’s presentation of trans women as threats to men, but it embraces the fetishistic and masochistic potential of that threat.

Without any sex and only including a brief glimpse of female breasts, “She-Man: A Story of Fixation” was the ‘60s equivalent of sissy porn. It includes an intro and coda from a doctor, portrayed by an actor so stiff that Clark must be deliberately parodying the ending of “Psycho,” offering 1967’s version of liberal tolerance. While that comes off wildly patronizing now, affirming Rose’s heterosexuality and calling Dominita a man while deadnaming her, it also explicitly says that there’s nothing wrong with a man enjoying cross-dressing, that it should be legal to be trans, and that Dominita went wrong only in her abusive behavior toward other people, not in her gender identity. These sentiments weren’t exactly common in the ‘60s, especially in a context this erotically charged.

“She-Man: A Story of Fixation” is an oddball curio; Jean Genet’s 25-minute short “A Song of Love” is a sublime reverie. Yet they’re both driven by sexual desire. A silent film made in 1950, it was the great French writer’s only foray into directing cinema. Using a prison setting he knew well from life, it turns cigarettes into phallic symbols. Genet claimed to have written his novels in prison with one hand while masturbating, and that sense of charged fantasy permeates every frame of “A Song of Love.”

The film’s characters can only touch each other in a dream scene; the prison setting means that in reality even the guard is confined to a voyeuristic round of gazing at men through the peephole. (Contradictorily but not uncommonly, “A Song of Love” finds erotic delight in police power while their control of prisoners plays out the worst aspects of the male gaze, even hinting at rape and murder.) Astonishingly for a film made this early, it shows men genuinely masturbating.

“A Song of Love” takes the subject of sex into a dreamlike direction that hardcore porn could have pursued but rarely has. The film layers fantasy upon fantasy, with a style driven by pure desire rather than storytelling logic, but ultimately, what matters is the ability to pull real tenderness and joy from such a brutal, isolating world. It was an obvious influence on Todd Haynes’ “Poison,” but the later film seems tame in comparison, even if it was controversial in 1991.

Marie Losier’s 2018 “Cassandro the Exotico!” echoes the underground superstars of Andy Warhol’s world. Shooting in 16mm and acting as her own cinematographer and sound recorder, she profiles Saul “Cassandro” Armendariz. He’s a gay professional wrestler in Mexico whose persona in the ring incorporates drag. “Cassandro the Exotico!” pivots around the paradox between the opulent theatricality of Cassandro’s act and his larger-than-life personality and the fact that wrestling is destroying his body. In an early scene, he shows off his many scars, and he constantly requires surgery. As he ages, the damage done in his younger days becomes harder to live with; in the film’s final scenes, he appears to have difficulty walking. A recovering addict, he says that child abuse led him to use drugs to cope with that mental pain, but one wonders if physical pain also played a part.

Losier’s rough style, however, emphasizes the grungier aspects of Cassandro’s life without doing justice to his aspirations toward glamour. She leaves in visual and audio noise; the sound is frequently murky, making one strain to hear Cassandro. This impressionistic view of Cassandro’s life falls flatter than Losier’s earlier documentary about the late transgender musician Genesis Breyer P-Orridge. Without being much interested in narrative, it still follows a predictably sad, even tragic trajectory.

For complete information on MUBI offerings and subscriptions, visit mubi.com.

To sign up for the Gay City News email newsletter, visit gaycitynews.com/newsletter.