A woman’s stormy relationship with her lesbian photographer daughter is chronicled

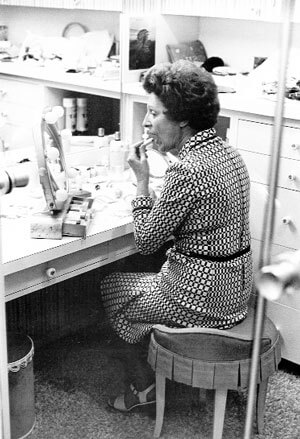

The author with her mother; Bertha Alyce focused on herself (B/W below).

Block says showing her subjects as honestly as possible is always her primary goal. To that end, she interviews the person she photographs for hours before taking a shot.

“Film and video are an integral part of my work, and through them and my photography, I try to let them speak in their own words,” Block explained in a recent interview. “When doing the ‘Rescuers’ photographs, I did two-to-three-hour interviews with [each subject], so I really knew what they looked like and how to take the picture.”

In contrast, Block had nearly 20 years to discern the truth in her mother’s life from behind her camera’s lens. The photographer spotlights her troubled relationship with her mother in her new book and accompanying DVD documentary, “Bertha Alyce: Mother exPosed.” Through roughly 150 photographs taken between 1973 and 1991, Block takes us into a stormy relationship between her mother—flirty, vain, oblivious Bertha Alyce—and herself, a serious, self-esteem-challenged, critical daughter.

What the reader sees are the many faces of Bertha Alyce: as pinup girl, posing nude in her bedroom; smiling in a bubble bath; beaming alongside her handsome husband and perfectly groomed children; looking elegant at numerous charity and social events; appearing rejuvenated post-facelift; showing signs of decline after suffering a stroke.

And then, there is the text. Block makes clear that from her earliest years, she did not like her mother. She describes Bertha Alyce as “unreliable”—alternately loving, then cruel. She recounts numerous slights. In one, she recalls her mother’s anti-gay reaction to her lesbian daughter.

Another portion of the text involves a session in which Block took photographs of her mother and herself together when both were topless: “I suggest we pose bare-breasted. You like the idea, even want me to take some pictures of you alone. Then you say it. Again. I knew you would. ‘It’s too bad your breasts aren’t as pretty as mine.’”

Some may interpret such a comment as a playful jest. Block doesn’t.

“Because I was her daughter and she loved me, she was sad that my breasts weren’t as pretty as hers,” she said. “Mother was a classic narcissist; I don’t think she had the capacity to consider my feelings. It was not ill-intended in any way—she just couldn’t go beyond herself, and she couldn’t even see the problem.”

It is possible to conclude that Block perhaps was too sensitive, and perhaps she was. A vignette featuring a bit of bickering between the photographer and her partner at home shows Block working overtime to avoid conflict. In another exchange with her mother, the women demonstrate that perhaps their problem simply was incompatibility: Bertha Alyce criticizes her child for spending too much time in therapy; Block counters that her mother hasn’t spent enough.

The book features comments from some of Bertha Alyce’s friends and rivals critical of her belief that men are more interesting than women—a view Block sees as being “self-hating.” There are also pictures of her life among Houston’s Jewish upper-class society and of her flirtations and marital infidelity. Some of the photos—in particular, those depicting her mother’s jewelry adorning a slice of cake, an unidentified baby’s penis, and the artist’s own pubic region—are troubling when one considers the possible motivations behind them.

However, Block takes pains to note her mother’s commitment to philanthropy. Bertha Alyce’s beauty and obvious joie de vivre are apparent in many of the photographs. And as the book makes plain, even this mother-daughter relationship evinced love and commitment. Whatever conflicts existed, Bertha Alyce was most generous in allowing her daughter to photograph her, even at her most vulnerable moments. And for all Block’s gripes about her mother, she seemed to spend a great deal of time with her.

In fact, by the end of the book—a shot featuring Bertha Alyce laid out in a casket after her death in 1991—one can’t help but like the woman and mourn her passing. The good news is, so does her daughter:

“I’m grateful she was my mother,” she says now.

Block insists that “Bertha Alyce: Mother exPosed” is not a re-do of “Mommie Dearest,” but a means for her to gain understanding. Reading the book and watching the documentary allow us to experience that reconciliation and to see the beauty in Block’s mother, and its advice—resolve conflicts before a loved one dies—makes this fascinating, sometimes funny, and often painful read a worthy one.

We also publish: