Soloman Howard in “Aida.”MARTY SOHL/ | METROPOLITAN OPERA

Leon Botstein came up with another intriguing novelty December 19 at Alice Tully Hall: after a staging of 1931’s play-to-be-read “The Long Christmas Dinner” by gay author Thornton Wilder, Botstein led his American Symphony Orchestra in Paul Hindemith’s 1960 operatic adaptation. Jonathan Rosenberg directed both multi-generation dramas capably, though I didn’t like his replacing Wilder’s use of coded doorways for characters’ exits in the play version with — in the case of mortal departures — melodramatic death rattles. It might be salutary to try the same approach and stage both the Wilde and Strauss versions of “Salome.” Here, with both pieces in English, it was interesting to hear how and where Wilder had slightly condensed or altered his play in crafting the libretto. For example, the departure of Sam as a doomed soldier in World War I evidently took on far greater meaning after the devastation of that war’s successor.

Hindemith’s harmonically deft score makes it the pivotal musical moment, with a striking sextet anchored by Sam — baritone Jarrett Ott, singing very suavely and with verbal point. The other outstanding members of the cast — most of whom did fine, though one frequently deployed veteran tenor came to genuine grief — were the two mezzos: refulgent, spirited Sara Murphy and rich-toned, subtly phrasing Catherine Martin. This was a well-conceived, timely evening.

December 30 marked my fourth viewing of the Met’s Salzburg-created Willy Decker “Traviata,” referred to by its non-fans among conservative operagoers as “the Red Dress ‘Traviata.’” The staging has its limits and demands a terrific lead performance. While nothing historic happened, I noted happily that the leading trio proved the most balanced I’ve seen yet in this tightly wound production: a repertory performance well enough cast and executed that no one who didn’t go in expecting Callas and Kraus could have felt cheated.

Marina Rebeka, announced as indisposed, sounded challenged for a mere few minutes before her voice freed up. She omitted Act One’s (in any event unwritten) high E flat but nailed the trail of tricky C sharps Verdi assigned. Rebeka showed more dynamic than coloristic range, but there’s no question she’s a genuine Violetta. She could phrase more on the words but does bring feeling and musicianship to her work.

Three revivals yield some bright spots

Marina Rebeka and Quinn Kelsey in “La Traviata.” | KEN HOWARD/ METROPOLITAN OPERA

Boyish and naive-looking, Francesco Demuro made an apt Alfredo and, though his voice isn’t huge, brought to bear pleasant Italian lyric sound and native phrasing that filled the bill very nicely. Quinn Kelsey sang Germont extremely well, a “real deal” Verdi baritone, and — I thought — with considerable dramatic nuance. Pray for him and/or Stephen Powell to jump in to the upcoming “Ernani“ revival.

The staging irons out most of the small parts into members of Violetta’s heartless fan club — perhaps just as well, since we had been dealt a disconcertingly raucous Flora and a mediocre Gaston. Only Maria Zifchak (Annina) and James Courtney (Dr. Grenvil) are allowed to create characters and these experienced artists did so effectively.

In the pit, Marco Armiliato’s leadership was sound and considerate.

Armiliato was less comprehensively in charge of “Aida” January 2, with two singers entering the cast anew; some tempi dragged.

Virginia-born soprano Marjorie Owens, an established artist in Germany — and co-incidentally married to Quinn Kelsey — joined the company with a risk that paid off: her first-ever Aida. Handsome onstage and a sensitive musician, she brought consistently attractive lirico-spinto tone to the testing role, rising easily to its iconic high notes. The audience was clearly happy. Her engagement is welcome; bring on “Don Carlo” and “Lohengrin,” please!

Carl Tanner’s rough-hewn tenor offered little sensuous tone but at least had the bite and consistency to project Radames’ music — until Act Three, when hit by an attack of phlegm with which he struggled manfully, trying not to spoil duet passages with Owens.

After years of soprano repertory, Violeta Urmana managed her old mezzo role of Amneris creditably but not without perceptible effort and some hard tone. George Gagnidze’s healthy-sounding old fashioned barnstorming suited Amonasro well. Two excellent basses appeared: Dmitry Belosselskiy, dramatically a cipher as Ramfis, and the exceptional recent debutant Soloman Howard, alert and striking as the King.

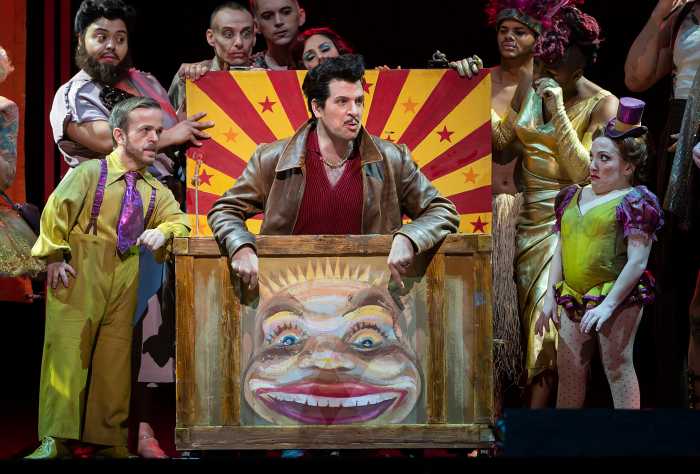

There’s pleasantly perverse life in Richard Jones’ veddy British “Hansel and Gretel” yet. January 3 witnessed a last-minute substitution by mezzo Jennifer Johnson Cano, who vocalized Hansel’s music well and fit right into the production. Stronger projection of words would have been welcome — but only Dwayne Croft’s strongly cast Peter succeeded in that respect, partly due to Andrew Davis’ sweeping but not sufficiently magical conducting.

Heidi Stober made Gretel unusually credible and sang decently, but her middle voice has little of the radiance Humperdinck’s music rewards. Robert Brubaker’s Witch remains amusing, but can’t we have the dramatic mezzo the composer envisioned? Michaela Martens — her Gertrud far better acted and sung than most — would be a strong candidate to sing the Witch, as might Urmana, or Deborah Voigt, a skilled comedienne audiences instinctively like with the right vocal format. A bright spot in the overall fun performance was the lovely-sounding Dew Fairy of star-in-the-making Ying Fang, still at Juilliard.

David Shengold (shengold@yahoo.com) writes about opera for many venues.