Michael Meads defies gay stereotypes in a Chelsea exhibit

Photographer Michael Meads focuses his lens upon his own social circles, directed by his search for unembellished masculinity. In earlier work, Meads captured our attention with casual homoeroticism depicted in images of young Alabama men toting guns, drinking beer, and proudly posing before a Confederate flag.

Meads, who trained as a painter, initially used photography as a visual studio resource, a fortunate decision. His sense of painting history and composition is carried over into his photographic collections, which stand on their own artistic merit.

Images of young men in provocative poses are not a recent notion. From Caravaggio to Jean Genet, the genre is rich with meaning and irony, particularly in today’s society, when the commercialization of the male physique is contrasted with the culture of the southern Bible Belt. In this context, the images from Meads’ most recent exhibition transgress the posturing of hyper-masculinity and uncover new terrain by capturing an ambiguous promise of violence or tenderness without relying upon the impossible unblemished male representation so prevalent in the mass media.

For example, “Love and Peace,” depicting two young men, one leaning back against the other, has a sweet sentimentality about it, and yet the facial expressions of the two men could be misleading. Are these men lovers or roughhousing cronies?

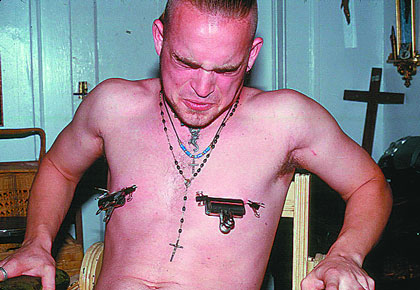

The same can be said for the image “Mardi Gras Reveler” depicting a man decorated with beads, hidden by a mask. Other images are more apparent in what they say about the model’s proclivities, such as “Ryan with Clamps II” depicting a young man with several binder clips on his nipples with rosary beads hanging loosely over his bare skin. Still there is ambiguity—is he cringing with pain or pleasure?

Meads’ men are human to a fault. Like the rough trade cast of characters in Jean Genet’s “The Thief’s Journal,” each man presents an outward appearance often of intimidating bravado and appeal while privately revealing their intimacies in a whisper or a howl. Like Nan Goldin’s work, Meads’ photographs contain a sense of empathy and trust between the photographer and model while placing the viewer into the awkward position of uninvited voyeur.

Perhaps Meads’ own words illustrate his admiration and fascination with the nature of masculinity represented in his art—a masculinity neither gay nor straight but entirely queer.

“They were like brothers, not lovers, and the ease with which they found being in each other’s company was fascinating if not aggravating. Perhaps their bond was best illustrated when Justin asked Allen to brand him using a blowtorch and a wire coat hanger shaped into a ‘J.’”

This sensibility is hard to maintain because it is so easy to fall back on self-mannerism, but Meads appears to be moving through the noisy gun-toting, flag-waving imagery of his earlier work and into something festive and thoughtful found on Carondelet Street in New Orleans.