Anyone who has nostalgia for the 1980s Lower East Side art scene — and who doesn’t? — will appreciate Brian Vincent’s spry documentary, “Make Me Famous,” about the largely unheralded gay painter Edward Brezinski (nee Brzezinski).

Brezinski was perhaps most famous for eating a donut made by artist Robert Guber that was on display in a bag at a gallery. The piece of art was toxic (it had a resin coating and may have been dipped in formaldehyde) which meant Brezinski has to be hospitalized and get his stomach pumped. As recounted in “Make Me Famous,” the incident was not likely accidental, despite Brezinski claiming he mistook the art for catering and was quoted in the newspaper as saying, “I was hungry.” More likely, it was Brezinski’s efforts to get his name in the paper and attract attention for himself. As various art world friends, including David McDermott, Duncan Hannah, and Peter McGough, acknowledge in the film, Brezinski was always “hungry and hustling,” but he never quite made it.

“Make Me Famous” is a sympathetic case study about Brezinski, who came to New York after attending art school in San Francisco. He hoped to find success in the downtown art world, but it mostly eluded him. Other artists, such as Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat, became superstars while Jeff Koons has a business acumen that Brezinski lacked. Moreover, Brezinksi painted in the expressionist style, but his style was not necessarily in vogue when graffiti art was trending. His effort to hang a stencil show was more in line with the 1980s zeitgeist. Brezinski was also an opportunist in his quest to get famous. His efforts to mimic the artist Stefano’s popular paintings, which were done on the back of leather jackets, failed as he quickly tried to create one and the still-wet paint rubbed off on folks at an event he was attending.

Yet Vincent has affection for Brezinski, who was a kind of lost soul. He had talent, as seen in several of his works, including a Nancy Reagan painting that is well regarded. He established The Magic Gallery out of his apartment that was directly across from a men’s shelter. But he often acted out of desperation. One interview recounts him going to a show and handing out cards promoting his own exhibitions, an art world no-no. That his handouts went from nice invitations to xeroxed pages shows his diminishing efforts over time.

One of the best anecdotes in the film involves Brezinski throwing a glass of wine in the face of Annina Nosei, an art dealer. As one version of the story goes, fellow artist Kenny Scharf was frustrated by how Nosei treated him and Brezinski took revenge. Nosei’s version differs, as she feels the incident was motivated by her not delivering on a promise that she made to visit Brezinski’s studio. Either way — and both recollections are probably true — the episode illustrates Brezinski’s pettiness.

Some of the saddest stories address Brezinski’s drinking. “It brought the dragon out,” one friend says, and hearing about the artist drunk and lying in the street, or getting into bar fights, indicate the depths of his despair.

Vincent uses visuals deftly to tell Brezinski’s story. He illustrates the aforementioned bar fight and other moments with animated panels. The filmmaker also uses photographs of key figures in the art world (e.g, Julian Schnabel) as well as film clips, such as one featuring Miguel Piñero reciting a poem, to immerse viewers in the 1980s downtown scene.

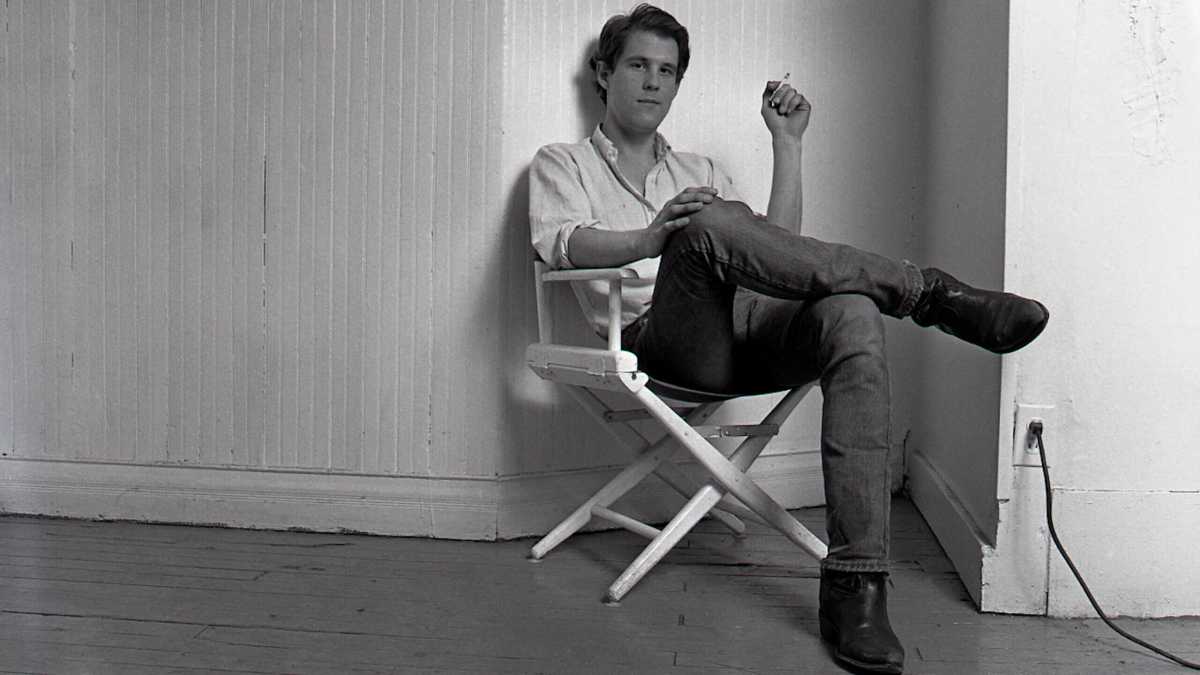

Curiously, Brezinski’s personal life is not recounted in any detail, which perhaps suggests he did not have much of one. He did go to gay bars, and he once met a collector, Lenny Kisko, who admired his work. The AIDS epidemic ravaged the downtown art community at the time, which may account for Brezinski’s lack of a boyfriend. But one can also surmise from the film that while the artist was not unattractive, he was probably difficult given his naked desire to become famous. Interviewees describe Brezsinki as “intense, confident, and charismatic,” but no one calls him sweet and loveable.

At one point in “Make Me Famous,” Vincent questions if Brezinski is still alive, as his death appears to be unrecorded in government databases. Did the artist fake his own death to generate interest and sales of his work? It is an interesting conceit, and certainly possible. The investigation is a bit shaggy, and the filmmaker trots out various cousins of the artists who are interviewed. They provide some observations about what Brezinski was like as a child — such as his dismay when there was no umbrella for him to use to walk to an outhouse on a camping trip. The “Is Brezinski dead or alive?” storyline gets dropped shortly after it is introduced, but it gets picked up later in the film yielding a satisfying answer.

“Make Me Famous” feels like this faked-death narrative was the motivation for making the film, rather than something that organically came up during the shooting of the documentary. Whether that is the case or not is irrelevant. What does matter is that Brezinski remains an object of curiosity 40 years after he first entered the art scene. Vincent’s engaging film delivers the fame Brezinski sought after all. What lingers, ultimately, is the sad fact that this portrait is only one of surely dozens, if not hundreds, of other artists whose lives never came to light.

“Make Me Famous” | Directed by Brian Vincent | Screening June 22-24 at the Roxy; June 23-25 at the New Plaza Cinema; and June 26-27 at the Alamo Drafthouse Lower Manhattan | Distributed by Red Splat Productions