Playwrights Craig Lucas and Tristine Skyler both undertake the challenge of tragedy

Tragedy comes in all shapes and sizes. Shakespeare wrote about it with a capital T, showing how hubris, betrayal, avarice, and other forms of human folly, of which we are all capable, can only end in tears.

In a post-9/11 world, after terrorism struck the United States on a scale never experienced before, finding humanity in an inhuman act takes a writer of immense sensitivity. Last year’s “WTC View” achieved that voice in the story of a man alone in his apartment in the days following the attacks.

With varying degrees of success, two new plays—“Small Tragedy” by Craig Lucas and “The Moonlight Room” by Tristine Skyler—try to get a handle how tragedy’s heartbreak takes a toll. One does so with skill, the other fails to hit its stride.

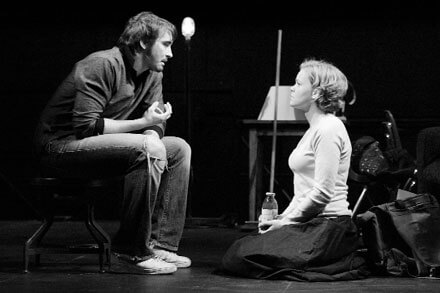

In “Small Tragedy,” Lucas tells the play-within-a-play story of a six-member cast of actors who rehearse a slimmed-down version of Sophocles’s “Oedipus,” only to find that the play’s themes of disloyalty and vengeance mirror their own self-doubts and misfortunes.

As in Lucas’s other plays, “Small Tragedy” brings together a seemingly mismatched group of people in an effort to universalize themes of love and loss. The fragile Jen (Anna Reeder) is cast as Jocasta opposite Hakija (Lee Pace), a young Bosnian man who escaped genocide. The ditzy Fanny (Rosemarie DeWitt) and the confrontational, HIV-positive Paola (Mary Shultz) are the play’s chorus of reason. Young, openly gay Christmas (Daniel Eric Gold), who plays various seers and messengers, falls for the play’s demanding, contrarian director Nate (Rob Campbel), Paola’s spouse.

Having his characters talk over one another or speak in chopped-up phrases, Lucas goes for a realistic approach that makes the show’s allegorical moments stand out in contrast. When he makes points about American’s blindness to the rest of the world’s problems, it’s clear that his is an “Oedipus” with aspirations beyond this one small stage.

The openly gay Lucas, best known for the queer-friendly plays “Prelude to a Kiss” and “Longtime Companion,” infuses gay themes into the narrative with subtlety. Like a typical group of actors, everyone is either gay, bisexual, or open to the idea of experimenting.

Lucas likes to keep a sense of mystery in his plays until the last moments, when the elements come together for a heart-stopping ending. The same happens here, and while the final scene is powerful, it seems like it comes from another play entirely. Still, as acted by one of the sharpest ensembles on any stage right now, “Small Tragedy” stands as one of Lucas’s best plays in years.

Pace, who received a Golden Globe nomination for playing a transgendered woman in the 2003 film “A Soldier’s Girl,” is mesmerizing as Hakija, using an easygoing sexuality and a perfectly-measured Eastern European accent to portray his character’s emotional ambivalence.

The even-keeled Reeder is captivating as Jen, a woman in conflict over a failed marriage. The eye-catching Gold, who appeared as a gay teen in “Beautiful Thing,” brings a devastating sensitivity to his role as Christmas.

Like a New York City cab driver worth his medallion, director Mark Wing-Davey takes risks with confidence, and keeps the action moving with abrasive stops and surprising starts that feel real, not forced. Under the hands of a less self-assured director, this play would drag under the weight of its difficult conversational passages. Here it soars, bringing tragedy to dramatic heights.

The buzz surrounding Tristine Skyler’s “The Moonlight Room” has been deafening. Her slice-of-life examination of today’s teenagers, wrapped around a story of small-time tragedy—depression, drug abuse, familial spats—was said to be the stuff of an important new playwright.

But after seeing this play when it moved Off Broadway following a limited run last year, it’s difficult to see why this show is making waves.

Skyler sets her play about a night in the life of teenagers Sal (Laura Breckenridge) and Joshua (Brendan Sexton III) in what has to be the most deserted triage room in New York City. There they discuss the travails of adolescense, from rumors of homosexuality to fighting with depressed parents.

The two have this unfocused, rambling discussion while waiting for their unseen friend Lightfield to be treated for a drug overdose. When Sal’s mother (Kathryn Laying) and Lightfield’s father (Lawrence James) enter the picture, the teen angst becomes almost unbearable in its languor.

The characters talk endlessly about nothing at all, moving the story along with all the swiftness of molasses. It doesn’t help that Sexton, an uninspiring actor, shares the stage most of the time with Breckenridge, a fine young actress with a mature sense of self. His unease is no match for her poise.

Skyler has been praised for having an ear for how teens speak, and that comes through at times, especially during Sal’s conversations with her distant mother. But that’s hardly enough to warrant writing a play this plodding. This is tragedy with a small t, written in a play with a small p.