When the coronavirus pandemic abruptly slammed New York City last year, homeless individuals were immediately impacted. Many providers offering much-needed in-person services quickly shut their doors, housing insecurity worsened, and COVID-19 spread through crowded shelters.

Now, nearly one year since the mass shutdowns in mid-March, homeless LGBTQ youth — already overrepresented among homeless individuals — have continued to find the COVID crisis consuming all aspects of their lives. Staff members who have weathered the storm are still strained.

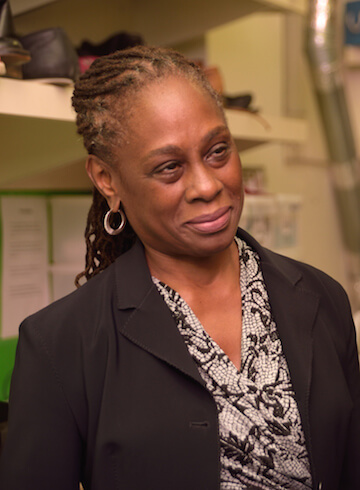

Kate Barnhart, the founder and executive director of New Alternatives for Homeless LGBT Youth, which helps queer young people transition out of the shelter system, said her clients are facing barriers to mental and physical healthcare as well as a lack of dedicated social spaces, among other lingering issues.

At Ali Forney Center, which provides housing and support services to queer young people, they are seeing similar problems — including mental healthcare needs.

“It is very much still a pandemic for us,” Alex Roque, Ali Forney Center’s president and executive director, told Gay City News. “People are coming to us really traumatized. They were already denied a home by the people who were supposed to love them unconditionally.”

The interruption of services early on in the pandemic led to a ripple effect that is evident today for clients of both New Alternatives and the Ali Forney Center. Barnhart pointed to an uptick in depression and anxiety cases, but she said her clients — who have to rely on Medicaid providers — are facing months-long waiting lists to see a doctor or a dentist.

“One girl was called for an intake, but they missed the call, and they were told, ‘Well, the next time available is six months from now,’” Barnhart said.

The very threat of COVID-19 infection is hindering some of the most marginalized homeless individuals — undocumented folks — from accessing basic healthcare. Barnhart said many undocumented clients have been reluctant to go to the doctor out of fear that immigration officials could sweep them up and hold them in custody, where they could be exposed to COVID-19 in crowded spaces.

For youth experiencing homelessness, some shelters seem to pose greater risks than others. While the Ali Forney Center has on-site testing four days a week, social distancing measures and proper protection are apparently hard to come by in city shelters, according to Barnhart, who said she has heard mixed reports about compliance at those locations.

“One client was freaking out because she got to a city adult shelter in Brooklyn where they were not doing any COVID compliance at all,” Barnhart said. “I’m hearing mixed reports about compliance.”

Those housing issues have been compounded by economic woes. Many homeless LGBTQ youth trying to establish their footing saw their work lives turn upside down during the pandemic. A whopping 90 percent of the kids at the Ali Forney center lost their jobs and 65 percent lost the education structure that was in place pre-pandemic.

“For our kids, it is another layer of devastation,” Roque said.

Barnhart and Roque both explained that their teams have had to absorb extra workloads to help meet their clients’ needs at a time when many places are still operating in a limited fashion.

In fact, closings of restaurants and other public spaces left many homeless individuals without anywhere to go as a last resort. Shelter beds have been in high demand during the pandemic and those who are unable to secure a bed are unable to fall back on other places, such as the subway, which is still not operating on a 24-hour schedule. And when shelters are closed during the day, folks have had fewer places to go.

“People went to Starbucks and they went to the public library; none of those are available,” Barnhart said. “Places like bathrooms in Port Authority, where people would brush their teeth, are just not available.”

“They want to be able to enjoy time with friends and eat dinner like they used to,” she said.

That all could change once more folks are vaccinated, but in the meantime, shelter residents are indeed eligible for the vaccine. New Alternatives and Ali Forney Center are helping to connect clients to vaccines and educating those who are hesitant to get a shot.

Roque said the city set up a “vaccination day” for kids at Ali Forney Center and his team has been helping kids schedule appointments to get vaccinated. They’ve also organized Q&A sessions to teach youth about the vaccine.

Barnhart said many clients have voiced suspicions about the vaccine, so New Alternatives surveyed them to understand how they felt and then posted educational flyers to inform folks about the vaccine. The organization is also creating TikTok videos about the vaccine and Barnhart documented her own experience getting both of her shots so others could see “nothing crazy happens,” she said.

It will still be some time until a sense of normalcy sets in for the general public, but homeless LGBTQ youth will still be facing adversity long after the pandemic subsides — and that’s been evident ever since they felt the weight of the pandemic at the onset.

“It’s important from an LGBTQ-related perspective to know that our queer homeless youth are always last in the line of services, last in the line of consideration, and last in line of being connected,” Roque said. “The pandemic has just exacerbated that. I don’t know when the awakening is going to happen, but our kids have been on the outs for a long time.”

To sign up for the Gay City News email newsletter, visit gaycitynews.com/newsletter.