From Cincinnati to Santa Fe, the summer opera season brought exciting shows across the country.

Cincinnati’s 2016 season introduced “Fellow Travelers” by out composer Gregory Spears — a deft, moving opera about Cold War homophobia in Washington, DC. Cincinnati Opera commissioned Spears — whose opera “Paul’s Case,” based on a gay-themed Willa Cather story, cemented his reputation in 2013 — to write another piece to open the 2020 season.

The composer worked with esteemed poet Tracy K. Smith (US poet laureate 2017-19) to develop an original story based on the vexed issue of collective Black land inheritance along South Carolina and Georgia’s sea coasts. On some of the only lands that formerly enslaved people were able to own after the Civil War, the properties have been subject to subsequent predation by state and local government and, especially, by developers of luxury resorts and golf courses finding one family member to sell, causing trouble for all the remaining relatives.

The scenario in “Castor and Patience” transpires against the background of the 2008 mortgage crisis during which many Black and underprivileged families lost their homes. Two cousins and joint heirs meet after many years and dispute their options; Castor —whose family moved north to Buffalo decades before — and his white wife, Celeste, need money for tuition (and a car and a house); Patience, the matriarch and historical conscience of the family lands, resists its diminution. Enhanced by scenes involving the family ancestors over a 140-year span, it’s a fascinating story with many interesting angles reflecting on larger issues in American racial and economic justice. The libretto is helpful when Smith trusts in her poetic gifts.

But there’s far too much didactic and expositional declamation, as if the creators were trying to explain all of the intersectional issues involved to earnest students rather than create drama. Stringent revision should remove fully half the text without damaging the work’s power and impact. This needn’t entail greatly shortening the score. Spears’ music — tonal and often justly termed “neo-baroque” — is ravishing. Both he and Smith have a gift for creating ariosos that encapsulate characters’ experiences and feelings. The penultimate scenes, deliberately left inclusive, needed a bit of tweaking in Kevin Newbury’s otherwise skillful staging. But the anthemic aria for Patience that concludes the opera has real power.

Excellent, individual-timbred lyric soprano Talise Trevigne proved the opera’s moral and emotional center, a truly inspired performance. Reginald Smith, Jr., made Castor’s pain vivid and delivered the text well; his imposing baritone could use more legato to serve the musical line. Vocally and dramatically, mezzo Jennifer Johnson Cano scored a triumph, making the potentially alienating outsider Celeste sympathetic. The youngest generation also yielded fine portrayals. The distinctive, strikingly pure soprano of Victoria Okafor’s Wilhelmina won sympathy. Rising baritone Benjamin Taylor — clearly indisposed and indeed masked — saved his best singing for West’s big moment, “When Grandmama was a little girl.”

Of Castor and Celeste’s children, out tenor Frederick Ballentine’s intense, incisively sung Judah had more substantial material to interpret than Raven McMillon’s appealing Ruthie. The whole ensemble under Kazem Abdullah’s sensitive baton performed strongly, with flashback scenes yielding outstanding cameo turns by tenor Victor Ryan Robertson as a reflective freedman in 1870 and rich-toned soprano Amber Monroe as Castor’s mother, Clarissa. Vita Tzykun’s simple but evocative designs conveyed a sense of the Sea Islands (as opposed to the Met’s current “Porgy and Bess,” evoking Robert Moses State Park. Cincinnati Opera and the creative team can take pride in this fine work.

Santa Fe has a proud history of world premières. This season brought “M. Butterfly” by Huang Ruo, which was postponed from the COVID-canceled 2020 schedule. Based on the acclaimed 1988 hit Broadway play by David Henry Hwang, who furnished the libretto, “M. Butterfly” has a complicated narrative. Drawing on a scandal that broke in 1983 involving a 20-year, espionage-leaking affair between French diplomatic official Bernard Boursicot and Chinese opera singer Shi Pei Pu, Ruo and Hwang, between them, also interrogate dualities in race, gender, and nationality, plus the legacy of Puccini’s iconic intercultural love story. While fascinating, the work would benefit from a revision that dialed back on some (not all) of the overt musical allusions to “Madama Butterfly.” Hwang has discussed how changes in the culture since 1988 have made the material less focused on the “reveal” that the opera singer (here “Song Liling”) is in fact a man, unbeknownst as such to his longtime lover (here “René Gallimard”).

The libretto handles that moment differently than did the original drama. Wisely, the creators have added more material about Song Liling’s experience surviving (barely) the Cultural Revolution and an effective late-in-the work solo “Eleven o’ Clock number” to award him more subjectivity. Even back in 1988, while dazzled by BD Wong and John Lithgow’s performances under John Dexter, I felt that Gallimard’s final fate (adapted from that of Cio-Cio-San), while perhaps meting out some redemptive cultural justice, was unduly melodramatic.

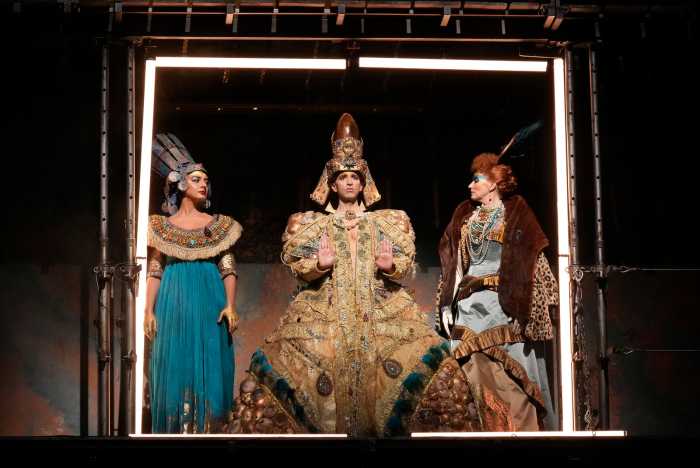

Though Boursicot was only 20 when he reached China in 1964, Gallimard in the play/libretto is very much middle aged. Though a fine, detailed actor and singer sensitive to phrasing and dynamics, Mark Stone’s otherwise still powerful baritone tended to waver in sustained passages. The evening’s triumph belonged to out countertenor Kangmin Justin Kim, thoroughly credible in all of Song Liling’s diverse aspects, and vocally remarkable even in traversing “Un bel dì.” Kim’s voice is more beautiful in slower legato sections than in the rare rapid-fire dialogue, and Ruo’s writing accommodated it tellingly. (To generalize, Ruo’s score proved more compelling and more rhythmically varied in vocal rather than instrumental passages.)

Kim and Stone’s joint emotional investment made the opera’s drama quite involving. Mezzo Hongni Wu proved to be dramatically telling and vocally fresh in smartly doubled roles: Comrade Chin (Song Liling’s Party handler and eventual tormentor) and Shu Fung (Song Liling’s servant). With a very difficult score to coordinate, Carolyn Kuan again proved her mastery of the contemporary idiom. Robinson ably utilized Allen Moyer’s spatially creative set, Greg Emetaz ‘s expert projections, and James Schuette’s costumes — spot on for both periods depicted. This opera should travel in Robinson’s production. The audience response was notably warm.

Any wisdom that “A Little Night Music” contains on par with what Ingmar Bergman’s delightful and philosophical 1955 film source offers decidedly resides in Stephen Sondheim’s brilliant lyrics rather than Hugh Wheeler’s stilted, wannabe-aphoristic book. But despite Wheeler’s clunking jokes, the parade of brilliant musical numbers sustains most of the evening. Barrington Stage Company’s starry revival under retiring director Julianne Boyd drew a capacity crowd to its handsome, intimate theater on a Thursday night (August 25) for a breezy, enjoyable take on the show. Boyd’s staging was admirably fluid and well-blocked, with choreography by Robert La Fosse and sound musical direction by Darren R. Cohen. Yoon Bae (set) and David Lander (lighting) achieved a candy-box pastel aura; but costumer Sara Jean Tosetti’s deployment of some inorganic mystery fabric slighted the cast’s women, save for Sierra Boggess’s stellar Countess Charlotte, pretty much ideal in song, speech, and deportment in a part that can yield a grating bid for Best Supporting Actress cred (that quality so prized by Broadway fanboys).

Jason Danieley and Emily Skinner — both with Broadway vocal chops and charisma to burn — took the leading roles (Fredrik and Desirée) strongly and in unhackneyed fashion. Skinner gave the show’s megahit, “Send in the Clowns,” a clear-eyed, rueful reading: no overwrought swinging for the bleachers. Similarly, I admired veteran Mary Beth Peil’s restraint in playing Madame Armfeldt not as a thundering Wildean gorgon, but as a classy operator; plus, she stayed on pitch — a rarity in this role. As Henrik — an unfair burden of a part as written — non-binary performer Noah Wolfe fared very well, with their theater-filling smile softening the scripted displays of adolescent angst (as recollected by less than fully empathetic adults). Sophie Mings put over Petra’s near-guaranteed showstopper ” The Miller’s Son” with flair and dynamic control. Of the scene-setting quintet — all professional presences — Stephanie Bacastow (Mrs. Anderssen), Adam Richardson (Mr. Lindquist), and Andrew Marks Maughan (Mr. Erlanson) showed outstanding voices. Slater Ashenhurst was duly unflappable and hunky as Frid (Wheeler’s dated, reductive caricature of a straight stud). Straightforward and never cutesy, Kate Day Magocsi was the most appealing Fredrika I’ve encountered.