Marc Handelman makes careful use of technique and materials to explore “nature”

Marc Handelman is a tricky painter. “Warm White Blizzard,” his current solo debut at Lombard-Freid Fine Arts, consists primarily of landscape paintings, each rendered with a kind of swoony technical bravura and revelry in the possibilities of materials.

“Hypothetical,” the first painting that one encounters upon entering the gallery, is a large-scale pastoral scene that sets up the contextual framework for the entire exhibition. The end of a road empties out into a shallow glen where the viewer is overwhelmed by a palpable yet impenetrable white light. The lush, manicured implications of the landscape suggest a golf course or a wealthy gated-community rather than a scene of untrammeled nature. The sparkle of fantasy is heightened by a collection of delicious scratched, scraped and flicked brushstrokes that could come directly from a Bob Ross “Joy of Painting” video.

Only a few of the paintings in “Warm White Blizzard” imply the sweeping vistas traditionally associated with landscape painting; the rest of the compositions are self-contained projections onto puddles and thickets of vegetation. In the gallery press release, Handelman cites his interest in the 19th century American landscape paintings of the Hudson River School and the Luminists and the “revelations promised” by such pictures.

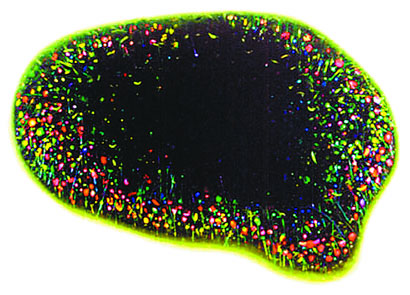

Rather than awing us with the enormity and magnificence of nature however, most of Handelman’s “landscapes” are appear as small-scale, idealized projections onto domesticated and/or internal spaces. This reading is further emphasized in “Dead Level” by the use of a central, reflective puddle-shape floating in the middle of a white canvas as an iris floats inside the whites of an eye.

Like other young painters of his generation, Handelman is deeply engaged in grafting the investigations of prominent 80s painters onto the contemporary interests of the academy. The depiction and meaning of various kinds of light—spiritual, atmospheric, photographic—as represented by the work of Ross Bleckner and Gerhard Richter gets taken for a new spin when combined with the mannerisms of Thomas Kincaid, America’s most collected artist and self-proclaimed “Painter of Light.” Even the range in size of the paintings themselves, from monumental to sofa-sized oils, serves to reiterate Handelman’s play on notions of high art, popular taste and the class aspirations embedded in particular genres of painting.

Here in America, we prefer our nature slathered up with a luscious, unctuous dose of kitsch.