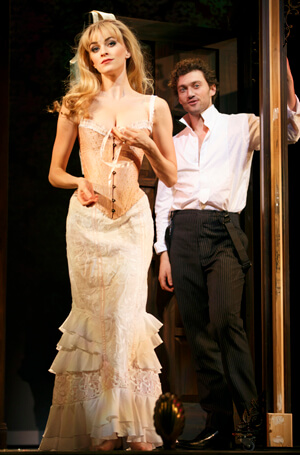

Lisa O'Hare and Bryce Pinkham in “A Gentleman's Guide to Love & Murder.” | JOAN MARCUS

There are going to be two diametrically opposed responses to the new musical “A Gentleman’s Guide to Love & Murder.” There will be those charmed by the merry mayhem of a serial murderer finding ingenious ways of knocking off everyone who stands between him and a lordship in Edwardian England. Silly antics, British pantomime-inspired characters, pastiche music hall songs by Steven Lutvak, and Robert L. Freedman’s clever lyrics are all in store.

Others, of course, will find the entire undertaking insufferable.

For the sake of Broadway’s financial viability, that second group appears to make up a minority — unfortunately, one I am a part of.

One new musical, one new play — stellar casts, but deadly dull

I’m not familiar with the novel by Roy Horniman on which this is based and have only a dim memory of the movie “Kind Hearts and Coronets,” which tells the same story, though it is not credited as a source for this undertaking. The story concerns Monty Navarro, who discovers after his mother dies that he is distantly related to Lord D’Ysquith. Having married a Castilian, the mother was banished from the family, and young Monty tries to claim a connection to the noble family but is rebuffed. Not to be deterred, he insinuates himself into the family and slowly begins introducing everyone ahead of him to their maker.

The heir-razing scheme is provoked by Money’s love for the beautiful Sibella, who will not have him since he is not rich — yet comes around when it appears he’s getting closer to the prize. A distant cousin, Phoebe, meanwhile, has set her cap for Monty, and romantic entanglements ensue. Monty, is of course, arrested, but in a plot twist right out of Gilbert & Sullivan, a happy ending all round seems likely.

The problem with this piece is that the overlong first act is all about killing off the people who stand in Monty’s line of succession, something that is not funny enough and soon becomes tedious. Jefferson Mays, who plays all the D’Ysquith victims, is a versatile and extraordinary actor, but his performance is largely pulling funny faces and adopting the poses of stock characters — from the effete and effeminate to the stuffy and stentorian. Appealing as Mays is, the charm wears off fairly quickly.

Things get a little more fun after intermission, as Monty’s romantic tangles move the plot. There is an inspired trio among Monty, Phoebe, and Sibella early on in Act Two that is the high point of the show and clearly demonstrates what might have been. For the rest of the piece, director Darko Tresnjak has done a by-the-number staging on music hall-inspired sets by Alexander Dodge, with nice period costumes by Linda Cho. The sound design by Dan Moses Schreier is sub-par, making a lot of the show sound muddy. With the exception of the lovers’ trio, the score, too, is less-than memorable.

Still, the lead actors distinguish themselves despite their surroundings. Bryce Pinkham, as Monty, has a terrific musical theater voice, a charming presence, and the ability to carry a show. It’s exciting to see him emerge from secondary roles as a true leading man. Two Broadway newcomers, Lisa O’Hare as Sibella and Lauren Worsham as Phoebe, are also finds, with beautiful voices and unmistakable star quality. Look for much more from these two in seasons to come.

You might be the sort of theatergoer who eats this stuff up. For me, it was more or less DOA.

Beth Henley returns to her quasi-Southern Gothic roots with a new play, “The Jacksonian,” getting its New York premier from the New Group. It’s a muddled, unfocused piece that tells the story of a dentist, Bill, hobbled by addiction and marriage problems, who has taken up long-term residence in a seedy hotel. Susan, his wife, visits him — and they fight — while daughter Rosy stays in the bar where a creepy bartender tries to seduce her by, of all things, swallowing cutlery. The other character, Eva, a maid and waitress at the hotel, has set her sights on the dentist.

The play is ostensibly told through the eyes of Rosy, who often comes downstage to offer information, such as where we are in the May to December timing of the story. This is a good thing, though the plot is mighty confusing even with the help. Henley has dashed off characters with her usual quirkiness, but the story has more violence than is typical for her, unfortunately with no discernible point to it. Setting the action against the racial upheaval in Jackson, Mississippi in 1964 simply feels gratuitous.

Arriving from the Geffen Playhouse, “The Jacksonian” boasts a cast that includes Ed Harris, Glenne Headly, Amy Madigan, Bill Pullman, and Juliet Brett. An accomplished lot, but under Robert Falls’ lackluster direction, they all seem to flounder. Henley’s wit and idiosyncratic humor shine through at moments, but not enough to enliven this turgid, baffling, and ultimately pointless play.