Kenneth Sherrill, a pioneering political scientist in analyzing the LGBTQ vote who was also the first out gay elected official in New York history, died Dec. 2 at his Upper West Side home with his husband and partner of 56 years, dancer and choreographer Gerald Otte, by his side. He was 81 and died from complications from several major surgeries this year.

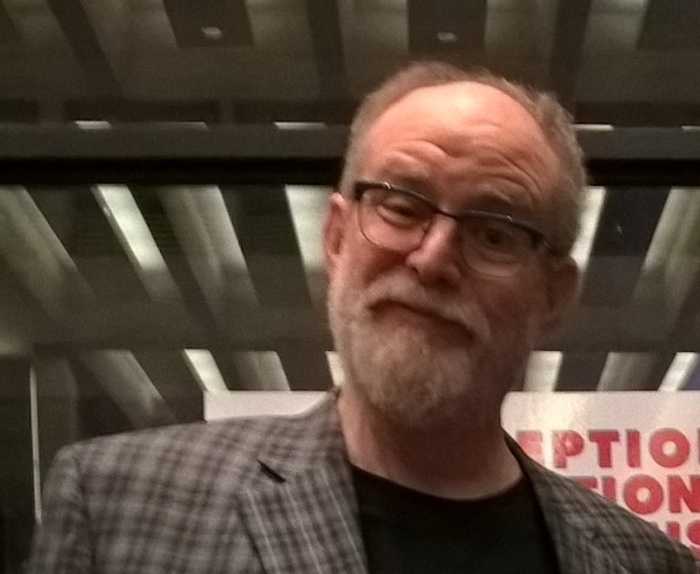

Sherrill had been the longtime chair of the political science department at Hunter College and became chair of the Hunter College Senate, where he championed campaigns to diversify curricula and staff. He was often the go-to political scientist New York journalists turned to for independent assessments of political developments.

“Ken laid the foundations for the study of LGBTQ politics in America,” Andrew Reynolds, who interviewed Sherrill for his book, “The Children of Harvey Milk,” about LGBTQ elected officials, wrote on Facebook. “He planted the seeds in the desert when everyone told him it was a fool’s errand. They told him queer stuff wasn’t politics, it wasn’t political science… Without his courage and persistence we wouldn’t have the canon of literature we now have which begins to understand the world of LGBTQ politics and the way queer people navigate the political world.”

A frequent Sherrill collaborator, Patrick Egan, assoc. prof. of politics and public policy at NYU, wrote that he was “a consummate academic organizer, leader and macher” and that “for years, his listserv ‘KensList’ was an eclectic and humorous source for news about politics, culture, and anything queer.” Egan and Sherrill discussed their groundbreaking study on the LGBTQ vote in 2007 on Doug Muzzio’s “City Talk” CUNY-TV show.

In 2017, the American Political Science Association, where he was a co-founder of the LGBT caucus in 1987, established the Kenneth Sherrill Prize for the best doctoral dissertation proposal for an empirical work on LGBTQ topics by graduate students and to broaden recognition of this work within political science.

One of Sherrill’s most quoted insights was that being LGBTQ was the biggest predictor that a person would leave the Republican Party if they were raised in it and become a Democrat. In analyzing the vote in 2000, he found that “lesbians, gays, and bisexuals are one of the Democratic Party’s most loyal voting blocs, despite the absence of one of the most important mechanisms for creating party identification: intergenerational transmission.” He and his co-authors examined “the impact of socialization within the LGB community for generating political liberalism, Democratic Party identification, and interest in LGB policies.”

He also was an advocate for party labels, arguing that they were at least one piece of information that voters needed to make decisions. When then-Mayor Mike Bloomberg tried to make New York City’s municipal elections non-partisan in 2003, Sherrill’s expert testimony played a key role in defeating that referendum overwhelmingly.

In 1992, before there was effective treatment for HIV/AIDS, Sherrill co-authored “What Political Science is Missing by Ignoring AIDS” in PS: Political Science and Politics. And in 1993 he and Marc Wolinsky edited “Gay in the Military: Joseph Steffan vs. the United States,” jumping off from the expulsion of Steffan from West Point — where he’d been a star cadet–in 1987 for being gay and arguing “that gays constitute a politically powerless class that has been unjustly deprived of its constitutional right to equal protection under the law.”

When New York City escalated the tax money that it was pouring into anti-LGBTQ religious schools in 2015, Sherrill told Gay City News, “I think the decline of traditional party organizations has magnified the ability of traditionally conservative religious organizations to turn out voters, sometimes enabling them to dominate primaries with no runoffs as well as to be able to deliver swing voters in closely contested elections.”

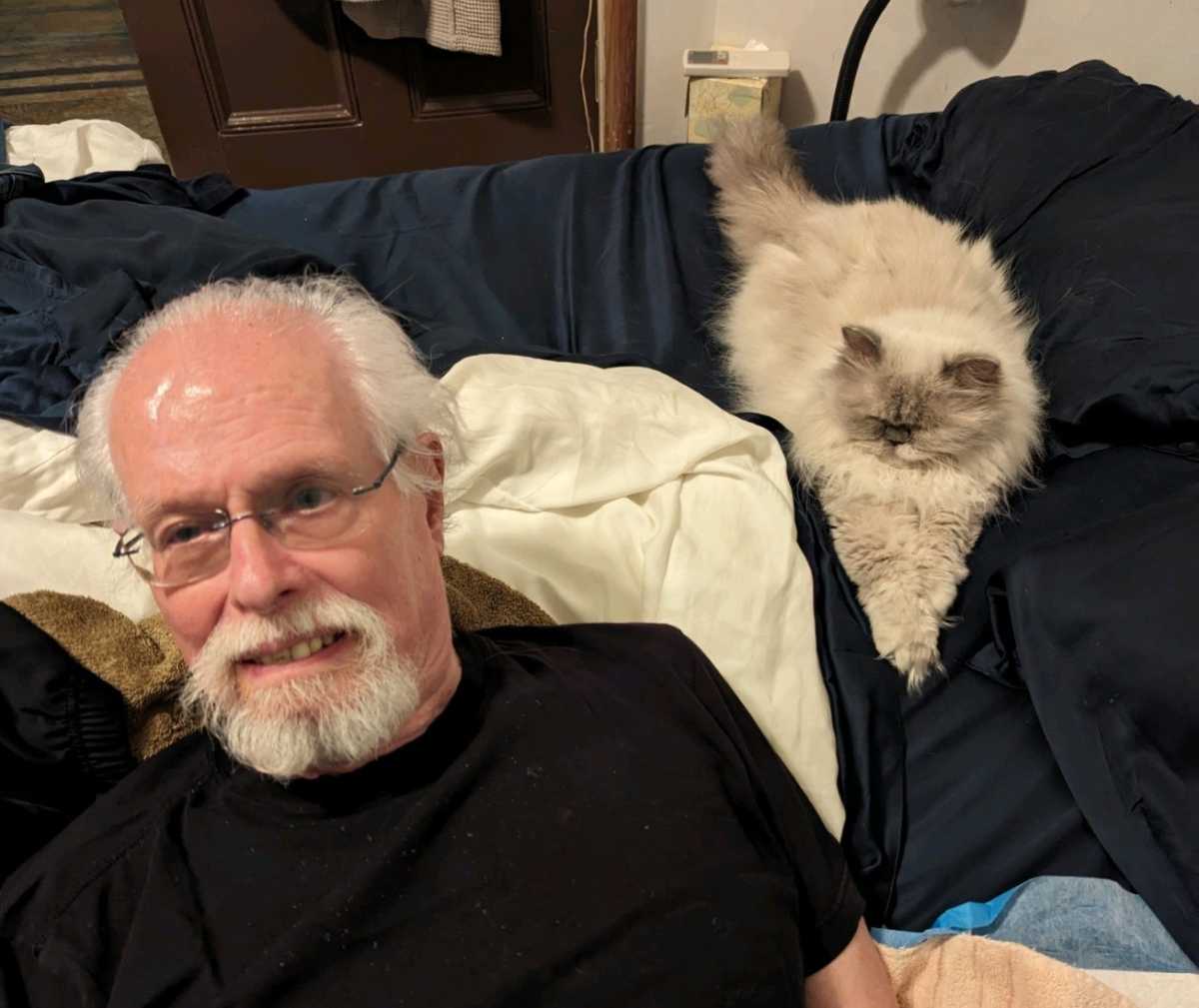

Sherrill published numerous scholarly works on LGBTQ and other topics, but perhaps his greatest achievement was his long relationship with Otte, who said they met just walking in Central Park one day. “He really looked at me,” Otte said, “and the next day I knew this was someone I would always be with. I knew that to find a life partner it had to be someone so much smarter than me that I would never be able to fool him.” They were married in 2003 in Canada when it became legal there by out Judge Harvey Brownstone.

Ken’s other lifelong passions, Otte said, were the Mets and opera.

Kenneth S. Sherrill was born in Manhattan but grew up in Brooklyn and graduated from James Madison High School and from Brooklyn College (1963). He did his graduate work in political science at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in the midst of the Civil Rights movement. He taught at Oberlin from 1965 to ’67 and from there he began his long tenure at Hunter College.

In New York, he immersed himself in city, state, and national politics. He campaigned for Robert F. Kennedy for the Democratic nomination for president in 1968, the year Kennedy was assassinated after the California primary.

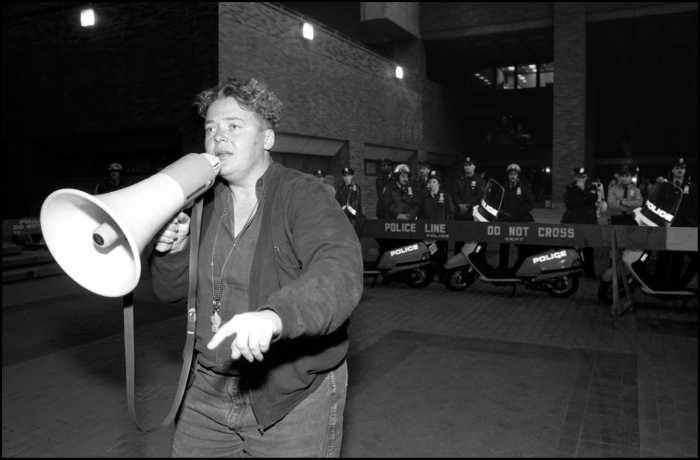

Sherrill also got involved in the burgeoning gay movement after Stonewall, becoming an early member of the Gay Academic Union and the Gay Independent Democrats that was founded by the late Jim Owles. When Owles was the first out LGBTQ person to run for New York City Council in 1973 — challenging the incumbent Carol Greitzer — Sherrill worked in that somewhat quixotic but groundbreaking campaign.

Sherrill’s historic breakthrough came in 1977 when he ran for Democratic district leader, a party post with no pay but one that was contested at the ballot box by party members. His win was the first for an out LGBTQ person anywhere in New York. (Ironically it was the year that the deeply closeted Ed Koch was elected Mayor.)

In remembering veteran gay activist Jim Levin when he died in 2019, Sherrill recalled their time together at the then-Gay Independent Democrats (GID), saying, “I’ll never forget the afternoon we spent registering voters in the Mineshaft at Gay Male S/M Activists’ Bizarre Bazaar… spending hours answering questions from prospective voters.”

Lawyer and activist Christopher Lynn, who was close to Sherrill since 1975 in GID, remembered him as a stickler for grammar and syntax in the club’s newsletters but also recalled an incident at a hearing on the City Council’s gay rights bill during one of the many times the bill was not allowed out of committee. Lynn said, “Ken began by saying, ‘I arrived here 12 hours ago prepared to provide appropriate remarks. Since we have been left to speak last, having been ignored and kept waiting, I find that inappropriate, and thus will tailor my remarks accordingly.’ He then tore the bark off the elected officials by announcing that their percentage of indicted Council Members exceeded the percentage of Hispanic youth arrested in the south Bronx.”

When Matt Foreman headed the National LGBTQ Task Force, he said that “Ken helped us understand voting patterns in anti-LGBTQ ballot measures. His analyses were critical in our being able to successfully target and move voters to support equality.”

His close friend for many years, Joan Tronto, professor emeritus at Hunter, the CUNY Grad Center, and the U. of MN, said, “Ken was wise and brave and just. He was also the most sex-positive person I have ever known.”

In these crises times for our democracy, Ken Sherrill’s clear-eyed assessments of the political scene will be sorely missed.

A memorial service will be held at a later date.