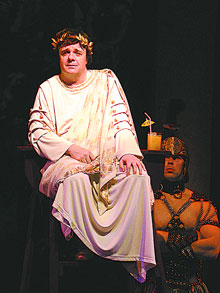

Nathan Lane is superb in adapting and representing a classic from Aristophanes

In high school biology class, we would pith frogs and pin them to a board, then stimulate them with electrical charges of increasing intensity in order to observe their muscle movements. The frogs were essentially brain dead, and yet they moved in response to the stimuli as if they were alive. Though ghoulishly entertaining to a teenager, this experiment had little relevance to my real life or professional experience. That is, until I saw “The Frogs,” the new Stephen Sondheim, Nathan Lane, Susan Stroman musical at the Vivian Beaumont.

The frog as a metaphor for unthinking passivity and the incapacity for independent thought is just one of the abundant joys in this incisively intelligent, profoundly moving and over-the-top hilarious show. The show is daring, passionate political theater wrapped in the trappings of musical comedy and classic spectacle. From beginning to end, it very nearly overwhelms the audience with its size and energy, brilliantly combining shtick, circus, romance, polemics and lots of lovely girls.

Anyone who has sat through a modern production of Aristophanes’ original drama from 405 B.C. knows that it’s barely accessible. In 1974, Burt Shevelove loosely adapted the classic for Yale Repertory, and for this production Lane significantly expanded that book, staying true to the essence of the play but adding gags that play to a modern audience and exploit current political themes. What is also retained from the original is an echo of the structure of the Attic drama of Aristophanes, which freely combined slapstick, satire and intellectual argument, leading up to catharsis and resolution. This is not the narrative style that most people are familiar with today, yet it is no more disjointed than the stultifying book for “The Boy from Oz” or the mess that passes for storytelling in the turgid “Mamma Mia!”

Moreover, Lane has found a source of satire in the very form of the piece. Dionysus, the god of wine and drama played by Lane, is on a serious quest. Appalled at the ongoing dissolution of civilization, Dionysus sets off for Hades to bring back a playwright who can inspire people to take action, to commit themselves to making a difference—heading across the River Styx, past the dreaded frogs and into hell. That’s pretty much the plot of the first act. The jokes are silly, crass and hilarious, delivered as only Nathan Lane can, particularly against Roger Bart as Dionysus’ slave Xanthias. In the second act, Dionysus travels through Hades and attends a couple of swell parties and then sets up a competition between George Bernard Shaw and William Shakespeare to see which of the great playwrights can save the world.

It sounds so simple, but it’s so much more than that. The exuberantly silly first act becomes chilling seen against the cacophonous vulgarity of our contemporary culture, when people care deeply about who wins a televised singing contest or gets to work with a self-aggrandizing real estate tycoon while our political leaders lie to us, and tinker with the economy for political purposes. The second act, the argument and catharsis, vilifies complacency, embodied, literally, by the frogs, and cries out for change.

What Dionysus learns is that reason, as represented by Shaw, is not enough to change minds or inspire action. Reason without the heart is vulnerable to persuasion, or as in clear jibes at the Bush administration, manipulation. People respond with emotion first and reason second. So one cannot win just the mind, one must also win the heart. When one wins the heart and stirs passion, as represented by Shakespeare, that passion combined with reason is an indomitable force for change—and hope.

The argument between Shaw and Shakespeare is not incongruous. It is a graphic illustration of the struggle for goodness to find a voice amidst the distractions, manipulations and superficiality. It is also, as would please Dionysus, amazing theater that draws on the form’s most potent strength—the power to astonish and provoke.

Nathan Lane deserves full credit for making this piece so powerful. He also gives a phenomenally committed performance as Dionysus. As always his comic timing is impeccable, and his idiosyncratic, now-familiar style invites us to like him. Like a good politician, he knows that in today’s world, “liking” can be more powerful than thinking.

But Lane doesn’t stop there, for the performance digs deeper as he takes us with Dionysus on the journey, particularly when he goes from mourning the loss of love, in the beautiful ballad “Ariadne,” to realizing the power of love when he meets Ariadne again in Hades. As a writer, Lane has given Dionysus quite a challenge, and as an actor he acquits himself beautifully.

Bart is charming as Xanthias. Peter Bartlett is hilarious as a very fey Pluto, but beyond the comedy he brings, he also provides a catalyst for Dionysus to understand more about the world—particularly that if one doesn’t fear death, a human’s potential is unbounded. Daniel Davis is fine as Shaw. As Shakespeare, Michael Siberry is astonishing, underplaying the role just enough to let Shakespeare’s words do the work, and then with the beautiful song “Fear No More,” finding the full expression of the heart—and the central tenet of the show.

Stephen Sondheim’s score is theatrical and emotionally honest, and typically witty. In addition to the songs mentioned earlier, “It’s Only a Play,” in particular, is a quietly ironic call to pay attention, and a dramatic turning point in the show that sets the tone for the more serious matters that follow.

Susan Stroman has done a masterful job with the variety of choreography, and her direction balances and makes sense of the changing energies of the piece. She fluidly moves the terrific company and the emotion throughout, never once allowing the visual sophistication to distract one from the heart of the piece.

“The Frogs” opens with an invocation on how to behave in the theater. It closes with an invocation on how to behave in life. You must have a heart of lead and a brain of mush if you leave this show without thinking about that and what you can do to effect change. Happily, you will also be participating in one of the original purposes of theater, reveling in its power instruct and inspire and delighting in a magic that can be as vibrant today as it was, presumably, in 405 B.C.