What does it mean to work as a blind artist? This question prompted out gay filmmaker Rodney Evans (“Brother to Brother”) to create his thoughtful, probing documentary “Vision Portraits.”

The film contrasts Evans’ own experience losing his sight — he suffers from a rare genetic eye condition, retinitis pigmentosa, that causes retinal deterioration — with that of three artists: John Dugdale, a gay, HIV-positive photographer; Kayla Hamilton, a dancer; and Ryan Knighton, a writer. The film sketches four portraits of individual artists adapting their process to line up with their limited visual perception.

“Vision Portraits” is enthralling because its subjects are never sentimentalized. Viewing them as “inspirational” is condescending and misses the point, the film suggests. Evans exposes himself and showcases the other artists because each has a commitment to keep working and producing art. His motivation to continue, he explains, is the same as the aspiration he originally had in becoming a filmmaker.

Evans opens the film with his own story of experiencing the shift in his vision that led to his diagnosis. To convey what he went through, he plays with the camera’s focus onscreen, blurring images, as in a walk through a New York subway station — showing just what he might see as his cane navigates a path through a crowd of faceless people. Evans also makes use of the camera’s iris to restrict the size of an onscreen image and of text to convey his thoughts. The combination of voice-over narration, written words, and visuals tells an emotional story.

Equally powerful is an Evans monologue later in the film recounting a harrowing experience on a train. After a stressful encounter — being hounded by a man who did not know he was blind — Evans has a startling experience. The anecdote is not intended to shock, but rather to give the audience insight into his world.

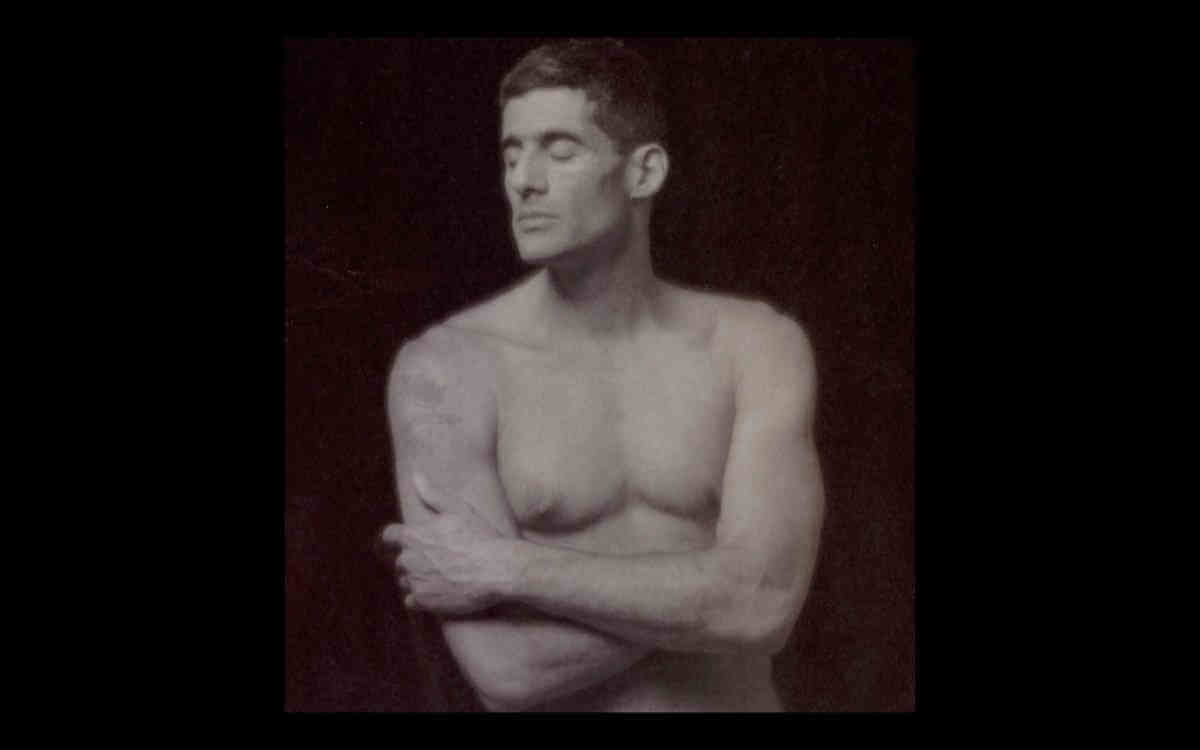

“Vision Portraits” is equally strong in presenting the other artists’ stories. Photographer Dugdale is introduced first through his gorgeous cyanotypes, many of which feature nude men or haunting self-portraits. The photographer describes how he suffered a stroke, which caused paralysis, and went nearly blind because of CMV retinitis, an AIDS-related infection. Several years later, he lost his sight completely. His condition did not stop him from taking pictures — with the aid of his assistants. Dugdale explains the “freedom” of being blind. He is able to create because he can still picture things he once saw. Evans shrewdly makes the screen go black as the verbally dexterous Dugdale lists a series of words that prompt viewers to picture the things he names in their mind. It’s an effective device for illustrating how Dugdale thinks — and why blindness is not limiting in his art.

The next portrait, of dancer Hamilton, describes the sensations she has when performing. She closes her eyes when she dances, which helps her focus on her movement. When Hamilton describes a pivotal appointment with an eye doctor that changed her life, the effect is profound rather than played for tears. She interestingly explains how she will ask the audience to experience her sightlessness by viewing her performance through one eye.

Before “Vision Portraits” presents its last artist, Evans addresses issues such as “passing as sighted,” to consider when and how he chooses to reveal his visual impairment publicly and professionally. He questions how the stigma of being blind might affect his future career plans and the shame and fear disabled people sometimes bring to their encounters in society. He also laments that as a 40-something gay man with a disability his efforts to find a partner-caregiver are not easy. Evans admits he was nervous about discussing his own condition in “Vision Portraits,” but it is precisely his openness about self-evaluation that makes the film so poignant and heartfelt.

The final portrait is of writer Knighton, who also has retinal deterioration. Evans juxtaposes a story of Knighton struggling to read a book he was holding — he could not see the text on the pages (and neither can viewers) — with a dazzling monologue he presents on stage about a rattlesnake rodeo he attended. These episodes show Knighton adapting to meet the challenges and fears he encounters but also demonstrate the power of storytelling, something both he and Evans obviously hold near and dear and is a source of their palpable bond.

“Vision Portraits” offers the uplifting message that visually-impaired artists can create work meaningful to themselves and to viewers. Evans has done that very thing with this remarkable documentary.

VISION PORTRAITS | Directed by Rodney Evans | Stimulus Pictures| Opens Aug. 9 | Metrograph, 7 Ludlow St., btwn. Canal & Hester Sts. | www.metro