A unanimous three-judge panel of the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals in Chicago ruled on January 17 that the state of Indiana must recognize the same-sex spouse of a woman who gives birth as the child’s mother and that she should be listed on the birth certificate.

The decision upholds a conclusion reached in 2016 by District Judge Tanya Walton Pratt, who held that the laws the state relied on in refusing to list the same-sex spouse on their child’s birth certificate were unconstitutional based on the US Supreme Court’s marriage equality ruling the year before in Obergefell v. Hodges. In Obergefell, the high court found that marriages of same-sex couples must be treated the same for all purposes as the marriages of different-sex couples.

The state of Indiana was unwilling to accept Pratt’s decision and pressed an appeal — despite the fact that just six after her ruling, the Supreme Court came to the same conclusion in Pavan v. Smith, ruling that Arkansas could not refuse to list such parents on birth certificates.

The state’s position was an insistent one — that it had a right to make a child’s initial birth certificate a record solely of the biological parents, as long as it allowed same-sex spouses to seek an amended birth certificate at a later date. Judge Pratt had rejected this argument, and the Supreme Court’s Pavan ruling vindicated her reading of Obergefell.

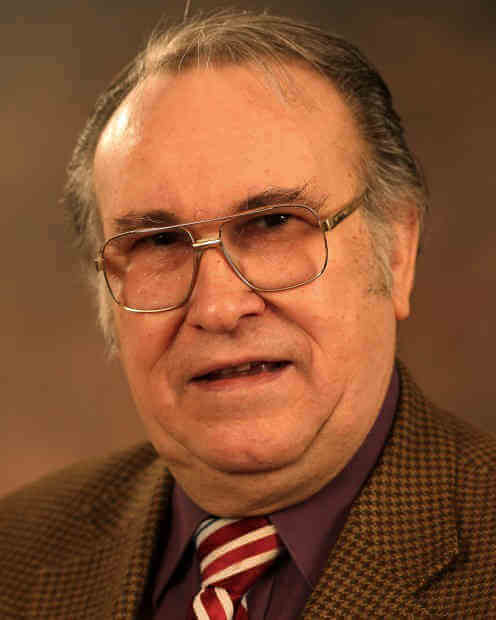

But the state of Indiana argued that “Obergefell and Pavan do not control,” Judge Frank H. Easterbrook explained in his opinion for the panel. “In its view, birth certificates in Indiana follow biology rather than marital status. The state insists that a wife in an opposite-sex marriage who conceives a child through artificial insemination must identify, as the father, not her husband but the sperm donor.”

The plaintiffs argued that Indiana’s statute is in fact status-based, not based on biology — noting that as a practical matter, women married to men who conceive through donor insemination routinely designate their husbands on a worksheet that state officials said is intended to elicit the sperm donor’s identity. Mothers are asked simply to name the child’s “father,” and it should surprise nobody that they usually list their husband.

Easterbrook’s opinion had a bemused tone regarding the state’s assertion about how women fill out the paperwork.

“Some mothers filling in the form may think that ‘husband’ and ‘father’ mean the same thing,” he wrote. “Others may name their husbands for social reasons, no matter what the form tells them to do. Indiana contends that it is not responsible for private decisions, and that may well be so — but it is responsible for the text of Indiana Code Section 31-14-7-1(1), which establishes a presumption that applies to opposite-sex marriages but not same-sex marriages.”

That presumption is that the husband of a married woman who gives birth is the father of her child.

“Opposite-sex couples can have their names on children’s birth certificates without going through adoption; same-sex couples cannot,” Easterbrook wrote. “Nothing about the birth worksheet changes that rule.”

Why should a married same-sex couple, entitled under the Constitution to have their marriage treated the same as a different-sex marriage, have to go through an adoption to get a proper birth certificate?

Easterbrook’s opinion identified another problem with Indiana’s existing way of dealing with birth certificates. What if the child of a same-sex female couple has two “biological” mothers?

“Indiana’s current statutory system fails to acknowledge the possibility that the wife of a birth mother also is a biological mother,” he observed. “One set of plaintiffs in this suit shows this. Lisa Philips-Stackman is the birth mother of L.J.P.-S., but Jackie Philips-Stackman, Lisa’s wife, was the egg donor. Thus Jackie is both L.J.P.-S.’s biological mother and the spouse of L.J.P.-S.’s birth mother. There is also a third biological parent (the sperm donor), but Indiana limits to two the number of parents it will record.”

Easterbrook concluded, “We agree with the district court that, after Obergefell and Pavan, a state cannot presume that a husband is the father of a child born in wedlock, while denying an equivalent presumption to parents in same-sex marriages.”

Easterbrook was appointed by Ronald Reagan, as was Judge Joel Flaum. The third judge on the panel, Diane Sykes, was appointed by George W. Bush. The ruling is the work of a panel consisting entirely of judicial conservatives appointed by Republican presidents, though the clear holding of Pavan v. Smith was such that they could not honestly rule otherwise.