COVER DESIGN BY MARCOS RAMOS

At 52, Michael Rizzo has endured a 13-year journey in combatting heart disease, one that began with shortness of breath and fatigue, a diagnosis of a heart murmur but nothing more serious, then a near-drowning incident that led to a more accurate diagnosis, followed, when he was 44, with open heart surgery. That proved to be just the start when he learned that the surgery had corrected only a portion of the problem facing him. Fourteen months ago, Rizzo received a heart transplant.

Saying he’s been “feeling much better in the last eight months” — beginning six months after the surgery — Rizzo acknowledged the challenges he continues to face: primarily the ongoing risk of organ rejection but also painful neuropathy caused by the drugs he takes to prevent rejection, but said that for now, “My body has completely accepted my new heart” and that he is “definitely out there in the world.”

Rizzo’s new heart and new life have definitely required adjustments, “learning to navigate my days and plan rest periods.” Living in Bergen County, New Jersey, with his partner of 18 years, Dr. Edward Hahn, Jr., a plastic surgeon, Rizzo said the limitations he faces — including having given up his career as a paramedic due to the risk that dealing with sick people poses to the compromised state of his immune system resulting from the anti-rejection drugs — are among “the challenges that you accept. Otherwise, I would have been dead.”

When he was a 39-year-old paramedic, with his partner Hahn then in medical school, Rizzo worked three twelve-hour shifts each week doing work that was physically and emotionally demanding — and with workdays that long, sometimes exhausting. That winter, he began to notice that he was experiencing greater shortness of breath and fatigue when the job required a lot of exertion. An asthma sufferer, he initially chalked the nuisance up to the cold weather and expected things to improve as the season changed. An active biker and hiker, however, he was nagged by pain in his arms he couldn’t account for.

Then, even as it warmed up, he found the weariness and shortness of breath becoming more common.

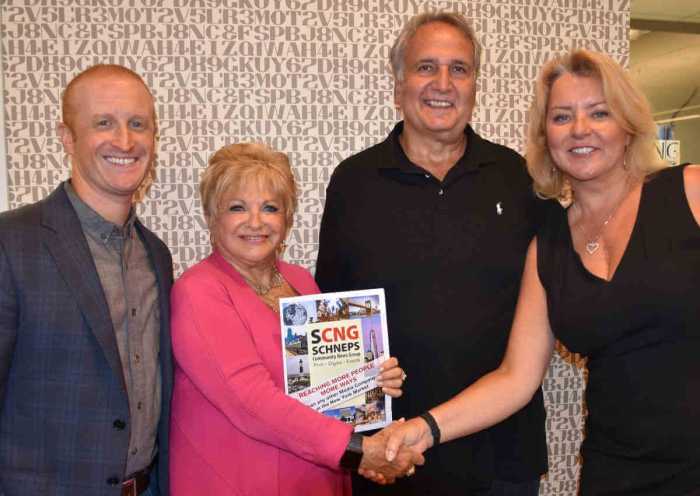

Michael Rizzo (in checked shirt) with his partner of 18 years, Dr. Edward Hahn, Jr., who live in Bergen County, New Jersey.

Rizzo’s general practitioner told him he had a heart murmur, an irregular beat that can sometimes be a benign symptom. An initial visit with a cardiologist turned up nothing of concern, and as his doctors kept exploring the underlying causes of his symptoms, he nearly drowned while swimming, overcome by his difficulty in breathing.

His condition, though, was hard to diagnose.

“They kept checking my arteries,” recalled Rizzo, which were clean and showed no sign of disease.

That’s because his problem was not in his arteries but rather in the heart muscle.

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, or HCM, is a genetic disease that causes thickening and scarring of the heart muscle, which when serious enough impairs it proper functioning. Rizzo was told that roughly three-quarters of those showing symptoms of HCM can be treated effectively with medication. And for several years, that’s the approach his care took, along with regular echocardiograms, which make use of ultrasound technology, and cardiac MRIs, which provide imaging of the damaged muscle.

Over time, it became clear that medication alone was not sufficient. At 44, Rizzo underwent open heart surgery — which Gay City News publisher Jennifer Goodstein writes about from her own experience here. The surgery was technically a septal myectomy, to reduce the size of the septum between the right and left ventricles in the heart and remove the obstruction inhibiting the flow of blood from the left ventricle into the aorta. The surgery also repaired the mitral valve controlling the flow of blood into the left ventricle.

HCM is hard to diagnose — in part because its rarity means it’s not often looked for — but the surgery Rizzo and Goodstein underwent has been performed successfully for decades, though not at just any hospital. The Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Association (HCMA), a support and advocacy group for people living with the genetic condition, certifies Centers of Excellence, and Rizzo chose to have his surgery at a Tufts University Medical School hospital in the Boston area.

Rizzo came out of the surgery well, and was able to continue working as a paramedic for another four years. Unfortunately, follow-up diagnostics on him showed that the enlargement in his heart was more pervasive than simply affecting the septum between the ventricles. It became clear that having already undergone surgery that only about a quarter of HCM patients have to face, he would eventually have to undergo a heart transplant. That’s something, he was told, that less than five percent of those with HCM must endure.

As Rizzo explained his condition, the heart muscle, which is viewed by doctors and physiologists as “smooth,” becomes fibrous and knotty in those with HCM. That fibrous knottiness that affects the septal wall of most people living with the condition was happening across his entire heart.

A heart transplant, of course, is an option of last resort, but having often dealt as a paramedic with bedridden people, Rizzo understood when his doctors told him that he could not wait too long, that the surgery cannot be performed on patients in a weakened state.

In preparing for the surgery, health care providers offer both psychiatric and financial counseling — the first to ensure a patient’s emotional readiness, the second to ensure that a plan is in place to cover the significant ongoing health care costs. Rizzo was cognizant of the tragic fact that receiving a new heart depends on somebody else’s death, but felt that his experiences over more than a decade had prepared him mentally to face what was in store.

Recovery, he explained, is “different for everyone.” Shortly after the surgery, Rizzo experienced a blood clot behind his knee that traveled to his lungs. The blood thinning medication needed to relieve that in turn caused bleeding in his GI tract. By the six-month marker, however, things took a turn for the better, normalizing his daily routine. Neuropathy limits his endurance in walking — no more hiking and biking — and his inability to go back to work as a paramedic has him on disability and reminds him of the infection risks he needs to avoid.

Mindful that his condition is genetic, Rizzo has located information on distant cousins on his mother’s side who experienced previously unexplained sudden cardiac deaths while still young. But the information has also allowed his family to be proactive. A few years ago, a nephew was diagnosed with HCM at 17, an age that will hopefully allow him to confront his condition early and effectively with the medications that help most of those affected live healthy lives without surgery.

Kim Walsh, a 38-year-old lesbian who lives in Sussex County, New Jersey.

Among those who are being treated with medication is Kim Walsh, a 38-year-old self-described butch lesbian who lives in Sussex County in northwest New Jersey. A teenage jock who pursued basketball and other vigorous sports growing up, Walsh recalled that, despite always “being on top” in games she played, she often experienced dizziness and shortness of breath. At the time, a doctor told her she had a heart murmur but explained it as a benign condition.

Walsh credits her general practitioner, Dr. Jennifer Horn of Newtown, New Jersey, with pushing for a better answer than a heart murmur as the cause of her problems. By the time she was 35, Walsh was dealing with a bipolar diagnosis that often left her anxious or depressed and had her on disability. She was also carrying 350 pounds in weight, which was a physical stressor.

Referred to the HCMA Center of Excellence at the Gagnon Cardiovascular Institute at the Morristown Medical Center, Walsh began treatment for HCM.

Referring to Gagnon’s Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Center, she said, “Their team is excellent… and excellent in handling the gay situation. I thought it was a life sentence. I found out it doesn’t have to be.”

Facing what she said is a dramatically oversized heart with an elongated mitral valve, Walsh has supplemented her medication with a dramatic weight loss regimen. Within two years of her diagnosis, she dropped down to 160 pounds, something she achieved primarily via diet given the limitations on her physical exertion.

Despite this impressive turnaround, Walsh has no illusions about what she faces.

“Everything is a struggle,” she said, adding that her wife, Lisa, who is 13 years older, is also on disability. Walsh has largely been abandoned by her family of origin, who don’t accept her sexuality, though she does speak to her mother occasionally. Kim and Lisa find no solace in local churches, who are unwelcoming to a lesbian couple.

At the same time, Walsh said her “condition is currently in check. I have pains, but within the normal range.” She finds relaxation in listening to music and in meditation, and the couple gets help from friends in addressing the financial challenges they face in living on disability.

As for her future prognosis, Walsh said she takes it from “doctor visit to doctor visit.”

Among the other strengths she draws on is the support network of the Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Association. The group’s founder, Lisa Salberg, herself an HCM survivor, is “an angel,” Walsh said.