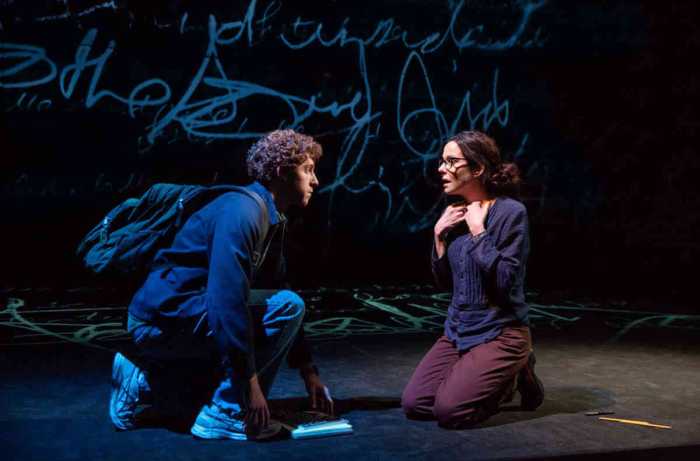

Harold Perrineau and Diane Lane in “The Cherry Orchard,” at the American Airlines Theatre through December 4. | JOAN MARCUS

Resisting the effects of time and the inevitable change it brings is futile — and a sure path to disappointment, if not tragedy. That resistance is, however, the stuff of theater, and few plays illustrate the struggle more clearly or compellingly than “The Cherry Orchard.” Though it depicts a Russian family in the first years of the 20th century, its themes are as relevant and resonant today as they were then. Human nature, the underlying theme of the play and virtually all of Chekhov’s work, is ever-resistant to change.

The play tells the story of a wealthy family that can no longer afford its estate, legendary for its cherry orchard, and is about to lose it in an auction. A real estate developer suggests that the orchard be razed and summer cottages built, which would solve their financial problems, but the family can’t stomach that change and, ultimately, all is lost. Themes of class differences and fundamental economic changes are filtered through the play as Ranevskaya, the matriarch, and her brother, Leonid — the older generation — hold out against Lopakhin, the young developer raised on the estate as a serf who is now trying to save its owners with his scheme.

In the new adaption at the Roundabout, Stephen Karam, author of “The Humans,” has preserved much of the scope and lyricism of Chekhov while updating the language. The problem is the compression of the play. In performance, Karam’s script clocks in nearly an hour shorter than the play as written, making this is a “Cherry Orchard” for the Twitter world. As with tweets, what’s lost are nuance, subtlety, and the richness of human foibles Chekhov relished in. Instead, they are only indicated.

Three plays explore relationships beset by a changing and random world

Many other playwrights have tackled this piece — with greater or lesser results. Tom Stoppard honored what Chekhov insisted was a comedy with heart and perspective that was fresh, while David Mamet less successfully applied his brusquer style.

If this adaptation feels like drive-by Chekhov, there are elements to recommend it — principally the performance of Diane Lane as Ranevskaya, the clueless aristocrat. As written by Chekhov, the character’s lack of connection to reality is vulgar, if not reprehensible, and Lane floats through the role, with Ranevskaya looking smashing in Michael Krass’ uniformly wonderful costumes, while virtually unaware of what is happening.

Harold Perrineau as Lopakhin is more agitated than is typical for the role, and also less kind, but the edge works in reflecting our contemporary world. And casting a black man in the role lends a contemporary focus on race to the dynamic.

Celia Keenan-Bolger is excellent as Varya, Ravenskaya’s adopted daughter who has managed the estate and sees all too well where things are heading, even if her love for Lopakhin is doomed to be unrequited.

The rest of the company does very well, though many scenes seem rushed and unclear. Director Simon Godwin hasn’t helped that much, with a breakneck pace perhaps deemed necessary for a contemporary audience but that sacrifices clarity. Playing the fourth act in contemporary clothing, which gives a time warp feeling to the undertaking, is quite simply theatrical overkill.

Scott Pask’s spare, monochromatic set, featuring Calder-like mobiles above a floor that’s a sliced-off tree trunk, is terrific, and Donald Holder’s lighting design is excellent. Krass’ gorgeous costumes use color to incisive and surprising effect.

Change is inevitable and can be good, and classics certainly cry out to be reexamined. But Chekhov is, after all, considered one of the first modern playwrights. This production raises the pertinent question of much more modern “The Cherry Orchard” needs to be.

John Mulaney and Nick Kroll in “Oh, Hello,” at the Lyceum through January 8. | JOAN MARCUS

“Theater is hot right now. There’s ‘Hamilton’… and nothing else.” So say Gil Faizon and George St. Geegland, two 70-something curmudgeons who somehow have gotten their very own Broadway show, “Oh, Hello.” The men are the comedic alter egos of 30-something Nick Kroll and John Mulaney. Appearing in deliberately false age make-up applied with only the merest attempt to convey physical age, the show is the kind of rollicking comedy that recalls the very best of Carol Burnett’s TV variety show and of Nichols and May.

Built on a ridiculous plot about roommates of 40 years losing their rent-controlled apartment and deciding to get rich via public access TV so they can have a roof over their heads, the show is rich in word play, malapropisms, and linguistic comedy that are consistently fresh. Both of these wonderful comics are new to me, though they have a huge following, with the characters hailing from Kroll’s show on Comedy Central.

In “Oh, Hello,” Kroll and Mulaney achieve that comic pinnacle of being both acid-etched and adorable, and while virtually every joke lands, some of their most trenchant are reserved for contemporary plays that don’t really go anywhere and just end suddenly. It’s wonderful to see the delight Kroll and Mulaney take in entertaining. That’s classic showbiz, and it helps make “Oh, Hello” an especially bright spot in contemporary comedy.

Denis Arndt and Mary-Louise Parker in “Heisenberg” at the Samuel J. Friedman Theatre through December 11. | JOAN MARCUS

“Heisenberg” may be just the kind of play that Gil Faizon and George St. Geegland poke fun at in “Oh, Hello.” That doesn’t mean the play is not thought-provoking and entertaining. It is a winding tale of two people who, having met on a bench in a railway station, fall into a relationship, of sorts. It is the sketchily told tale of the aggressive Georgie Burns and her pursuit of a much older man, Alex Priest. Whether she is really in love with him or simply using him is often unclear.

Georgie is a force of nature, a receptionist at a private school, who overwhelms the more sedate Alex, a butcher with a shop in London. Georgie lies and manipulates, and Alex plays along. The play exists in the collision between these two characters.

Though this is barely enough to hang an 80-minute one-act on, the exceptional performances of Mary-Louise Parker as Georgie and Denis Arndt as Alex alone on an almost bare stage mine the substance of Simon Stephens’ play as best as could be done.

The title is ostensibly a nod to Werner Heisenberg who is noted for developing the uncertainty principle in quantum physics (I had to look that up). That’s a little cute, as we’re clearly supposed to consider the random nature of human interaction that spins until the play just stops, unresolved and presumably still spinning in the darkness. At the performance I saw, the audience didn’t know the play was over, something that happens in the theater with increasing frequency lately.

The uncertainty principle here is whether this brief, discursive play is worth your $150. To see Parker and Arndt at the top of their form, yes. To see a manipulated and often forced character study, perhaps not so much.

THE CHERRY ORCHARD | American Airlines Theatre, 227 W. 42nd St. | Through Dec. 4: Tue.-Sat. at 8 p.m.; Wed., Sat.-Sun. at 2 p.m. | $59-$149 at roundabouttheatre.org or 212-719-1300 | Two hrs., 20 mins., with intermission

OH, HELLO | Lyceum Theatre, 149 W. 45th St. | Through Jan. 8: Mon.-Tue., Thu.-Sat. at 8 p.m.; Sat. at 2 p.m.; Sun. at 3 & 7 p.m. $59-$149; telecharge.com or 212-239-6200 | 90 mins., no intermission

HEISENBERG | Samuel J. Friedman Theatre, 261 W. 47th St. | Through Dec. 11: Tue.-Wed. at 7 p.m.; Thu.-Sat. at 8 p.m.; Wed., Sat.-Sun. at 2 p.m. | $70-$150;at telecharge.com | 80 mins., no intermission