A one-woman show underscores how feminism was cooked up in America’s kitchens

The kitchen as a metaphor for life is not a new conceit, but it is still a powerful one. Few other rooms in the house have the associations of a kitchen: food, unity, how we express ourselves.

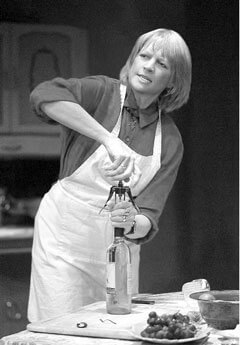

So the kitchen is the perfect, albeit inevitable, setting for the new play “My Kitchen Wars,” adapted and performed as a one-woman show by Dorothy Lyman from Betty Fussell’s book of the same name. It tells the story of Fussell’s growth and emergence as a fully realized, independent woman from a post-World War II wife and mother who chafed against her assigned role as cook and caregiver, yet did them anyway with all her heart. Fussell, however, finds her liberation not by abandoning the kitchen with which she had become comfortable, but through it—allowing, against many odds, her inner artist and writer to find a voice and a truth.

This is not feminist dogma. Yet in its intimacy and honesty, this story provides an unvarnished look into the world of women and the struggles they endured as the nation entered a new era. For baby boomers whose mothers always seemed so together and, well, perfect, the play is a peek under the veneer of that myth and becomes a heartfelt and deeply moving portrait of one woman, who clearly reflects many of her peers. For a gay audience, the play is especially moving as it provides a complex and evocative vision of the costs of living in a repressive culture.

In performance, all of this is done with a light touch, liberally laced with a quiet and wry humor that is more marveling than militant as we watch Betty shed the skin she was given and take on her own. She does not minimize the costs, the heartbreaks, or even the deep anger and resentment, but her evolution is presented with such mature wisdom that the bad things that happen are viewed from the perspective that all the yesterdays could not be avoided if one wants to live in the present. It is the most clear-eyed and unsentimental pictures of women in that period I have ever encountered, and as such finds power in its intimacy.

It is also one of those rare occasions when a one-person play is the perfect medium for the message. Because Betty’s journey is so personal, though universal, adding other characters would diminish it, and to make a realistic film out of the memoir would trivialize and distance the play’s themes. By virtually sitting with Betty in her kitchen––the tiny 78 St. Theatre Lab has been brilliantly transformed by set designer George H. Landry––the audience develops an easy rapport with her that gives the subtext a subtle but compelling role in the play.

By the end of the evening, one both knows this woman and understands her on a personal level. From her first childhood experience to a celebration of eating alone, Betty’s journey is a process of discovery, surrender, choice, and hope. Betty is wonderful because she is not perfect. She is compulsive and frightened, risk-taking, and conservative, struggling to fit a mold, only to find that she is the mold.

Lyman plays Betty with phenomenal skill. She is always charming, never indulges herself in emotional excess, and yet we know the feelings she is suppressing, the struggle to express herself, what it takes finally to leave her husband and the life that has constrained her. It is an understated performance, and as the character finds her power through food and drink, Lyman actually prepares an elaborate dinner for one—the ultimate symbol for how much she values herself—including a soufflé. Through her detailed performance, we see how the implements, the batterie de cuisine, that she wields have always been her arms, her armor, and ultimately her ticket to freedom. It is as fine and moving a performance as you will see anywhere in New York right now.

The scenes are punctuated with songs from cabaret artist Melissa Sweeney. It’s a deft touch. Sweeney is a lovely performer, perfectly in tune with the energy of the piece.

This is such a sweet, honest, and compelling piece, the only regret you’ll have is that you won’t get to share Betty’s meal—like the rest of the production it looks perfectly done.