BY ARTHUR S. LEONARD | A US magistrate judge has denied a request by a gay HIV-positive man to have his identity shielded from public exposure in a discrimination lawsuit he has filed against his former employer in the New Orleans federal district court.

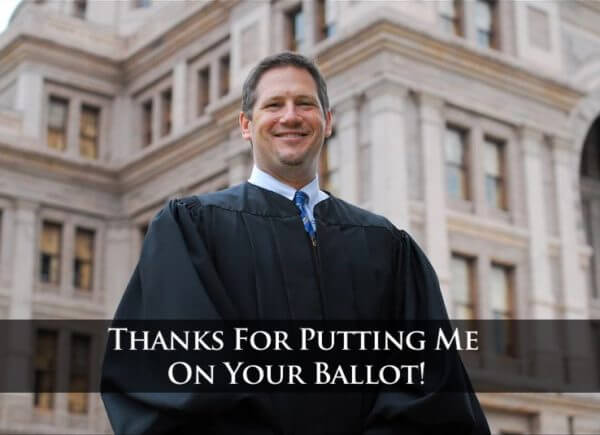

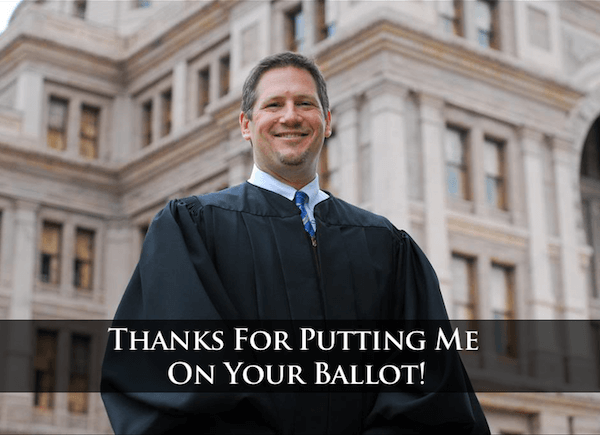

“The only specific concern expressed in plaintiff’s motion papers,” Magistrate Judge Joseph C. Wilkinson, Jr., wrote in a September 5 ruling, “is that he ‘believes… he will have difficulty finding new employment should his HIV status be made public.”

The plaintiff is claiming violations of both the Title VII sex discrimination prohibitions in the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), which prohibits employment discrimination based on disability. In his motion to Wilkinson, the plaintiff states he “is an HIV-positive homosexual male with an understandable fear that if his health status is made public, it will negatively affect his life in multiple ways.”

New Orleans federal court finds plaintiff faces no “greater threat of retaliation” than others alleging bias

Wilkinson pointed out that the general rule is that plaintiffs must sue in their own name and that Title VII does not establish any exception. Courts, however, sometimes exercise their discretion to allow a particular plaintiff to proceed as “John Doe” or “Jane Roe” — the most famous example being the Roe v. Wade case, in which the trial court accepted the plaintiff’s argument that due to the controversial nature of abortion laws and her status as an unmarried pregnant woman challenging the Texas prohibition, she should be able to proceed anonymously.

In the New Orleans case, the plaintiff did not want to be forced to out himself as both gay and HIV-positive to be able to vindicate his rights in federal court.

The plaintiff cited a 1979 decision by the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals — under whose jurisdiction Wilkinson serves — that identified “homosexuality” as one potential ground for allowing a plaintiff to file anonymously. While criminal sodomy statutes then still on the books no longer exist, it remains true that neither Louisiana nor the federal government yet has any specific prohibition on sexual orientation discrimination in the workplace.

But Wilkinson asserted that the court’s record is “presumptively a public record, open to view by all, and requests to seal the court’s record are not lightly granted or considered.” The plaintiff had the burden to show that his interest in protecting his confidentiality outweighed the public’s “common law right of access” to such a record.

“Although sexual preference is certainly a personal matter and homosexuality is one of the ‘matters of a sensitive nature’ identified in the above-cited Fifth Circuit opinion, public opinion about both homosexuality and HIV-positive status has become more diverse and accepting during the 35 years since that decision,” Wilkinson wrote. “Certainly, only the seriously uninformed today act under the erroneous impression that HIV transmission might occur in ordinary workplace activity.”

Pointing to same-sex marriage litigation in Louisiana, he continued, “Other plaintiffs asserting claims in civil actions in which their sexual preference is an issue have done so publicly and in their real names.”

And, Wilkinson added, “Defendants — whose names have already been published in the court’s record — have been the subject of public accusations by plaintiff that may do damage to their good names, reputation, and economic standing.”

The judge also noted the “high” level of public interest in the issues being litigated, since most federal courts have rejected claims that anti-gay discrimination is covered by the 1964 Act’s ban on sex discrimination and there is a divide among courts about whether the ADA automatically protects an HIV-positive person if there is no specific evidence of a physical or mental impairment.

Concluding that the plaintiff in this case would not face any “greater threat of retaliation than the typical plaintiffs alleging Title VII violations under their real names and not anonymously,” Wilkinson denied his motion.

Focusing only on the Title VII sex discrimination issue, however, ignores the HIV confidentiality side of this case. The ADA recognizes the importance of this issue by requiring employers to preserve the confidentiality of their workers’ medical records.

Employers may well understand that an HIV-positive employee poses no risk of contagion in the workplace, but they could potentially discriminate against applicants based on assumptions they make about work attendance, longevity on the job, or the impact of their presence on co-worker morale.

A decision requiring an HIV-positive person to disclose their serostatus in a public record as a condition of seeking discrimination redress seems inconsistent with the ADA, since it could strongly discourage HIV-positive people with potentially valid claims from filing suit. It is particularly at odds with the 2008 ADA Amendments Act, which Congress adopted in order to make clear that HIV-positive people are protected against discrimination, regardless of what some uncomprehending federal trial courts had concluded in the previous 18 years.