Self-taught and working-class, Allan Bérubé revolutionized queer history

At the height of World War II in 1943, a couple of soldiers stationed at South Carolina’s Myrtle Beach Bombing Range — Woodie Wilson and a six-foot-four queeny blond MP known as “Sister Kate” — had met so many queers in uniform on other Southern military bases they decided to start a newsletter for them, which they called the Myrtle Beach Bitch.

“It was a gossip column,” their friend and “subscriber” Norman Samson recalled. “Who was going with whom, who was sleeping with whom. Who had graduated from a Pfc. lover to a captain or a lieutenant… It was almost like receiving a newsletter from home, because it was the only communication we had about people we had met in other bases. It let us know who was overseas and where they were… We were saying, ‘Guess who’s still alive!’”

With the help of a straight soldier who was in charge of the base’s mimeograph machine, the uniformed duo managed to produce five issues of the newsletter before they were caught and sent to federal prison for a year.

This is just one of many priceless nuggets of hidden gay history to be found in a new book just published by the University of North Carolina Press, “My Desire for History: Essays in Gay Community and Labor History” by the late Allan Bérubé, who died unexpectedly of ruptured stomach ulcers in 2007 at the age of 61.

Bérubé achieved near-iconic status in the gay world in 1990 when he published his groundbreaking book “Coming Out Under Fire: The History of Gay Men and Women in World War II,” which was later turned into a documentary film for PBS by Arthur Dong from a script by Bérubé.

There were only some half-dozen books on US gay history at the time, and in rescuing from total oblivion the untold stories of the gay “greatest generation,” Bérubé helped launch the first serious national debate over the exclusion of gays from the military. He became a central figure in that fight, and worked closely with Senator Edward Kennedy’s staff in opposing the anti-gay compromise that became known as Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.

As a community historian, Bérubé, a working-class college dropout, was a total autodidact, and the tale of how he researched and wrote “Coming Out Under Fire” is a truly heroic one. It’s lovingly told in a biographical introduction to this new essay collection by the two distinguished queer historians who edited it — the University of Chicago’s John D’Emilio, whose numerous books on gay history include a superb biography of Bayard Rustin, “Lost Prophet,” and Stanford’s Estelle Freedman, whose latest book is Modern Library’s “The Essential Feminist Reader.” Both professors were old friends and gay movement comrades of Bérubé’s since the late 1970s.

Bérubé’s penurious parents raised him in the squalid confines of a trailer in the heavily-polluted industrial town of Bayonne, New Jersey, from which the bright young lad, a voracious reader, escaped by winning scholarships — first to a tony Protestant prep school, where he was often snubbed by his WASP fellow students because he waited on them in its dining room to help pay for his studies; then to the University of Chicago, where he studied English literature.

But when his college roommate, a fellow working-class scholarship student for whom he had an unrequited love, was killed in a race-related murder, a shattered and depressed Bérubé dropped out.

As a conscientious objector to the Vietnam War, Bérubé was influenced by the anti-militarist writings of the pacifist lesbian Barbara Deming (subject of a biography by Martin Duberman published earlier this year — see this writer’s March 2, 2011 review in Gay City News, “Lives of Courage and Commitment”).

Bérubé did his alternative service working for the Quakers’ American Friends Service Committee in Boston starting in 1968. It was there, while on a Peace Walk to spread the anti-war message to surrounding small towns, that he first heard of gay liberation, and began attending meetings of the Student Homophile League at MIT. He soon became part of the Boston collective that launched Fag Rag, a seminal and insouciant radical gay paper of the early gay liberation movement filled with provocative articles (like historian Charlie Shively’s “Cocksucking as an Act of Revolution”.)

In 1971, Bérubé, ever in search of community, moved to San Francisco, where he joined a radical hippie commune of weavers, and where, inspired by the publication of Jonathan Ned Katz’s monumental 1976 document collection “Gay American History,” Bérubé, then 30, turned his passions to gay history. He spent long hours in libraries and, as D’Emilio and Freedman write, “gave himself the equivalent of a graduate education in research methods and historiography.”

Together with writer-activists like Jeffrey Escoffier, Amber Hollibaugh, and the late Eric Garber, as well as D’Emilio and Freedman, Bérubé founded the San Francisco Lesbian and Gay History Project to create a new kind of community history. His first major production was “Lesbian Masquerades,” a lecture-slide show on women who passed as men in the late 19th century and whose stories he gleaned from local newspapers of the period.

Bérubé was a powerful presenter who took his slide show all over the Bay Area, making him something of a local gay celebrity, and then on an East Coast tour.

A chapter based on “Lesbian Masquerades” is included in the new essay collection. So is a chapter on the horrific gay-baiting of the 1959 San Francisco mayoral campaign, when Republican Mayor George Christopher, who’d launched a crackdown on queers upon taking office four years earlier, was (rather surprisingly) attacked by the Democratic candidate, Russell Wolden, for having allowed San Francisco to become “overrun by deviates,” a headline-grabbing charge that “hit the city like an earthquake.” Decried by most of the local press, Wolden and his queer-bashing campaign were easily trounced by Christopher.

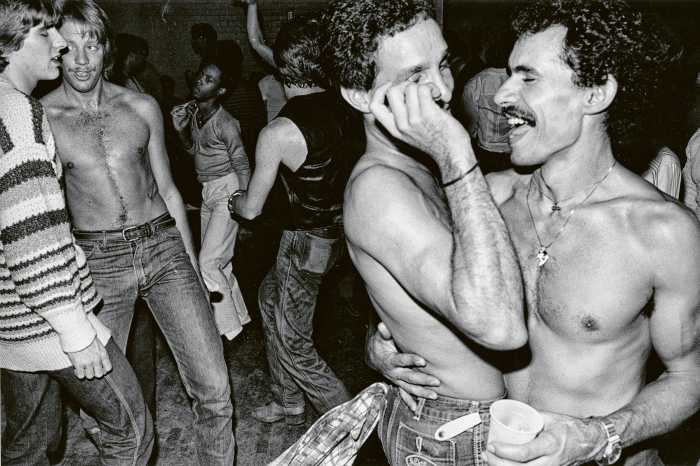

Another Bérubé slide lecture included in “My Desire for History” is a history of gay bathhouses, produced in response to San Francisco’s closing of them in the early years of the AIDS crisis. Bérubé used historical precedents to argue that those bathhouses should instead become the axes for safe-sex education.

But the intense interest in his next slide lecture, “Marching to a Different Drummer,” about queers in World War II, led him to abandon an earlier plan to write a gay history of San Francisco and concentrate on his research about the war, which consumed most of the 1980s.

He took this slide show all over the country, from college campuses and local organizations to the homes of veterans, and each presentation unearthed new sources, surviving gay veterans who wanted their stories told, yielding a host of private letters and journals stashed away, forgotten in the attics of the vets and their families. Bérubé also obtained documents harvested under the Freedom of Information Act (requests resisted by the military brass) and from the National Archives.

What made Bérubé’s work heroic was that, as D’Emilio and Freedman point out, this self-taught man from a humble background “labored with very few material resources to support his research. He enjoyed none of the benefits that a faculty position at a university provides: no salary or health insurance, no paychecks during the summer, no funded sabbaticals for writing. For a while, he went back to weaving scarves, which he could do in the evening, and sold them by word of mouth through friends and acquaintances. He worked as an usher and manager in local movie theaters and registered with an agency for temporary office workers.”

Bérubé confided to his journal his frustration at not having nearly enough time to write: “This business of squeezing it into lunch hour or Saturday nights is for shit…”

In 1983, Bérubé fell in love with Brian Keith, a young British biochemist at the University of California whose research specialized in plant growth. But just three years later, Brian was diagnosed with AIDS and withered away rapidly in the days before protease inhibitors. Allan nursed him through the last days of his illness, an experience recounted in a chapter of the essay collection. Brian, having extracted from Bérubé a promise not to let grief impede the World War II book’s completion, made him the beneficiary of his life insurance policy. And so, out of Brian’s tragic death came the money that allowed Bérubé to finish “Coming Out Under Fire,” whose enthusiastic recognition by the critics eventually led to him winning a MacArthur Foundation “genius grant.”

Berube’s last project was to have been a book about the Marine Cooks and Stewards Union, an estimated two-thirds of whose members were “queens,” as they called themselves. The MCSU flourished from the 5,000 members it had at the time of the 1934 maritime strike to a high of 19,000 after the Communists and radicals who had taken it over insisted on reversing the color bar and admitting blacks, Chinese, and other people of color. That leadership used strikes to end the owner-imposed skin-color bar to employment on cruise liners.

Many of the elected union leaders were openly gay and even held high positions in labor federations. One straight African-American official of the MCSU said that “in 1936 we developed this slogan: It’s anti-union to red-bait, race-bait, or queen-bait. We also put it this way: if you let them red-bait, they’ll race-bait, and if you let them race-bait, they’ll queen-bait. That’s why we all have to stick together.”

Thanks to the domestic Cold War, McCarthyism, and the incessant red-baiting by a rival company union, the MCSU was destroyed in the early 1950s, and many of its leaders jailed under the Taft-Hartley Act prohibiting Communists from holding union office.

The chapters in “My Desire for History” drawn from Bérubé’s drafts of his unfinished book portraying the solidarity created between the “queens” and other workers in their struggles are fresh and new, even to those of us familiar with labor history. Sadly, he died before the MCSU’s untold story could be completed.

Equally penetrating are Bérubé’s reflections on the inter-relationship among class, race, and gender and sexuality that animated so much of his work, for he insisted, correctly, that “an understanding of virtually any aspect of modern queer culture must be, not merely incomplete, but damaged in its central substance to the degree that it does not incorporate a critical analysis of modern class relations.”

D’Emilio and Freedman deserve our unreserved thanks for rescuing these significant Bérubé writings from obscurity, and for making his courageous life’s story available to us all. “My Desire for History” will be a rich and thought-provoking addition to your library. Do yourself a favor and buy it.

Copies of Allen Bérubé’s “My Desire for History” may be purchased directly from University of North Carolina Press atuncpress.unc.edu/browse/book_detail?title_id=1905.

MY DESIRE FOR HISTORY:

Essays in Gay, Community,

& Labor History

By Allan Bérubé

Edited with an Introduction by

John D’Emilio and

Estelle B. Freedman

University of North Caroline Press

Cloth $65, paper $24.95;

332 pages