Andreas Gursky’s large-scale photographs nearly overwhelm with their visual detail

Currently on view at the Matthew Marks Gallery is an exhibition of ten large-scale photographs by Andreas Gursky made over the last three years. This is the German artist’s first one-person show in New York since his retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in 2001.

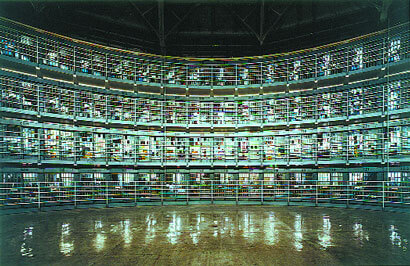

Gursky’s new work continues to explore vast spaces recorded internationally. These large-scale photographs (approximately nine by seven feet), which record enormous amounts of visual information, were made in Mexico, Brazil, Japan, Vietnam, and throughout the United States and Europe. The detailed visual presentation in each photograph forces a change in the viewer’s perspective between the view from far away and that seen up close, a nearly overwhelming sensory experience.

In “Rimini,” the patterns formed by bathers, umbrellas, and chairs running for acres up the coast structure a fascinatingly intricate tableau.

In “Madonna, 2001,” a stadium full of fans regard the spectacle of the performer’s Drowned World Tour. Their fascination is focused on the technology and effects; the show of lights, speakers, video screens, confetti, dancers, nearly nude men suspended upside down by chains. The fans are the largest part of the spectacle, Madonna on stage being only a small focal point in the photograph’s visual information.

Two pieces, “Greely” and “Fukuyama,” are both images of cattle ranches, the former a sprawling farm complex in rural Colorado and the latter a sort of cow high-rise outside Tokyo. The image of level after level of cattle vertically arranged is, for us, a quite seductive yet disorienting preparation for the mass slaughter that we know is coming.

The piece in the show that left me feeling uncomfortable was “Statesville, Ill.” Gursky captures the interior of a state penitentiary; the inmates stare out at the viewer from within the abstract grid of the prison cells. Here the depth of field is not as great as in the cattle ranch photographs and the scale is more recognizably human. The perspective is still straight on and captures every detail; human incarceration is used as a compositional device. The fact that this is a prison and humans are being held against their will, much like the cattle, creates a visual anxiety and lends the work a psychological heft.

The fact that more detail is captured in the photographic moment and manipulation than the human eye can record is part of what makes Gursky’s work so interesting for me. By capturing the scale of what humans can and do accomplish, Mr. Gursky’s art helps me get the big picture.