Reality-based horror and the last Hollywood poet

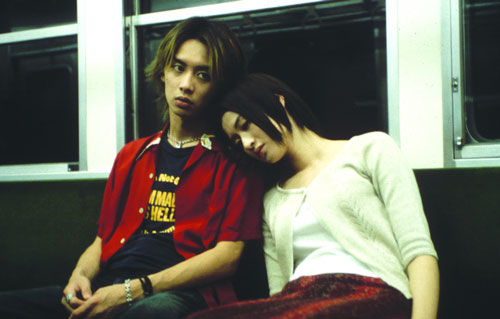

Haruhiko Kato as Kawashima and Koyuki as Harue in “Pulse,” a horror film about technological anxiety and loneliness by Kiyoshi Kurosawa.

Unlike 2004, 2005 wasn’t marked by a flashpoint like Mel Gibson’s “The Passion of the Christ” or Michael Moore’s “Fahrenheit 9/11,” or even Lars von Trier’s “Dogville.” Instead, apathy seemed to dominate film discourse, apart from those cute penguins that marched their way into the multiplex and gay cowboys who may be about to do so.

1. “Caché” (Michael Haneke) A brilliantly directed anti-thriller about a TV host’s horror of being watched, “Caché” let a slight amount of light into Haneke’s bleak world. Even so, it made the audience work hard for tenuous and ambiguous conclusions, rather than offering the satisfactions genre films usually provide.

2. “Grizzly Man” (Werner Herzog) Years after the New German Cinema’s heyday, the documentary boom has helped put Herzog back on the map. A great doc usually requires a great subject—in amateur filmmaker and grizzly bear enthusiast Timothy Treadwell, Herzog found a replacement for his “best fiend” Klaus Kinski. Surprisingly, this dialogue with a dead man soberly examines the romantic worldview behind many of his films—being a visionary won’t keep you from being eaten by a bear.

3. “Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance” (Park Chan-wook) With three films released in New York this year and an enormous amount of ink spilled about them in print and on blogs, Park has finally established himself as one of world cinema’s most controversial directors. Is he a Hitchockian master or a reactionary glorifying vigilantism? I’ve swung back and forth, but “Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance,” the first installment in a trilogy about revenge, is an unshakably brutal depiction of a society where CEO and anarchist alike share the same lack of values. Vengeance is everywhere, but the sympathy must be supplied by the spectator.

4. “Tropical Malady” (Apichatpong Weerasethakul) Who would have guessed that William Blake has a successor in Thailand? This two-part gay love story, which starts off banal and ends up aiming for mythical transcendence, made the rest of the year’s romances (whatever their orientation) look trivial in comparison.

5. “The Holy Girl” (Lucrecia Martel) “The Holy Girl” may be the first film whose framing is influenced for the better by a lifetime of watching cropped videotapes Conflating a girl’s burgeoning sexuality with her urge to spiritually redeem a man who gropes her in a crowd, it creates a visual vocabulary all its own to express the turmoils of female adolescence.

6. “The New World” (Terence Malick) The year’s most powerful heterosexual love story, it suggests that Malick is the last poet left in Hollywood. Improving on “The Thin Red Line” in several respects—particularly the use of voice-over—it contains some scenes combining music, live sound and montage so powerfully that my jaw was on the floor.

7. “Kings and Queen” (Arnaud Desplechin) If “Seinfeld” was a show about nothing, “Kings and Queen” is its opposite—a film about everything Desplechin can cram in. Taking family melodrama as its starting point and pumping it full of literary references, sharp mood changes, and a little bit of hip-hop dancing, it suggests that he can do almost anything he wants and put a personal stamp on it.

8. “Pulse” (Kiyoshi Kurosawa) The best horror film Michelangelo Antonioni never made, “Pulse” risks foregoing a logical story in favor of evoking horrific desolation. Its ghosts aren’t nearly as scary as its vision of a Tokyo emptied of life. If its fears about an Internet-driven apocalypse now seem slightly dated—it was made in 2001 and only released in the U.S. this year—keep in mind that it looks back to Hiroshima and includes imagery predicting 9/11.

9. “A History of Violence” (David Cronenberg) Despite the title, I’m not convinced that this film has anything profound to say about bloodshed. However, it does offer a scathing picture of American life at its most phony, where social roles—whether they be gangster, family man, or teenage bully—are drawn from pop culture and have little to do with people’s real inner lives. This is the kind of American film it takes an outsider to make.

10. “Darwin’s Nightmare” (Hubert Sauper) Essential, indelible, and harrowing, this documentary starts out with a small subject—the destruction of a Tanzanian lake by imported perche—and turns into a portrait of globalization at its bluntest and most callous. Balancing crude, even ugly direction with very careful editing, it’s as scary as a great horror film but all too real.

James Benning’s “13 Lakes,” Hong Sang-soo’s “Tale of Cinema,” Philippe Garrel’s “Regular Lovers,” Katsuhito Ishii’s “The Taste of Tea,” Nobuhiro Suwa’s “A Perfect Couple,” and Takashi Miike’s “Izo” didn’t make it off the festival circuit into commercial release, but they deserved a better fate. At least “Izo” is currently available on US DVD.

Runners-up: “The Devil’s Rejects” (Rob Zombie), “Innocence” (Lucile Hadzihalilovic), “Kung Fu Hustle” (Stephen Chow), “Land of the Dead” (George A. Romero), “Mysterious Skin” (Gregg Araki), “She’s One of Us” (Siegrid Alnoy).

gaycitynews.com