After six months in a Marine prison, Stephen Funk is ready to continue denouncing Iraq war

Two years after joining the armed forces, Marine reservist Stephen Funk is out of uniform and out of jail. Since his February release from the Marine brig at Camp Lejeune, Funk’s hair has grown longer, but the young man’s conviction that the United States made a mistake in invading Iraq remains unchanged.

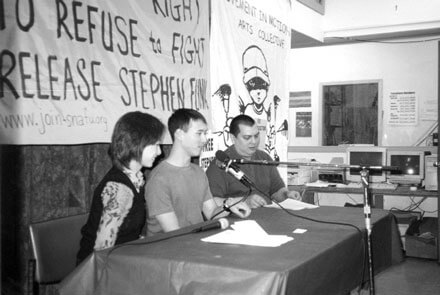

On March 2, Funk reiterated his opposition to the war at a victory party of sorts at the International Action Center on West 14 Street.

Before taking to the front of a room packed with supporters, two rappers performed a number, “Stephen Funk, True War Hero” that included lyrics noting some of the details in the case of a handsome Filipino American who dropped out of college to spend time redefining his priorities and then refused to report for duty when his California Marine unit organized for a call up following the invasion of Iraq.

“He refused to be acquitted/he was gay and went to jail,” rapped the two young men, as Funk’s mother, Gloria Pacis, an artist, watched. The two rappers smiled broadly when they finished, an exhilaration others seemed to share just by having Funk in their midst.

Funk did not make a speech once he sat at a table in front of a large hand-painted banner that read: “Support the Right to Refuse to Fight.”

“I don’t know what else to say. It might be better to go to questions and answers,” he said, adding with a note of self-deprecation that “youthful stupidity” led him to enlist.

“I still haven’t received my discharge,” Funk said. “For a few days after my release, I was leery and checking if I was being followed.”

Funk’s leeriness is not altogether unwarranted. His family and the war resistors who encouraged his refusal to report for duty maintain that Funk’s six-month jail sentence following a court martial in New Orleans last year was issued as a warning by the Pentagon that it would brook no defiance from men and women in uniform. Furthermore, Funk’s advocates insist, the Californian received a stiffer sentence than usually meted out for the charge Funk was convicted of because military officials were incensed that Funk had given television interviews in which he denounced the Bush administration’s invasion of Iraq.

Funk was never prosecuted under the military’s Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell policy prohibiting gay and lesbian service members from serving openly. Rather, military prosecutors filed a charge of unauthorized absence against him for the 47 days following his call up when Funk refused to report to his base.

Funk has never denied being absent. “I was giving interviews,” he remarked on March 2. “They knew where I was.”

Funk engaged in a conversation with the supportive audience for about two hours. “I swore into the military about two years ago,” he said at one point, adding, “and it was really stupid. I didn’t know my rights and when I knew I could apply for conscientious objector status, I filed.”

The military never honored Funk’s objector application. Rather, it chose to prosecute him for unauthorized absence.

“The brig at Camp Lejeune was the most I ever fit in the military,” said Funk. “I was there with all the other misfits. Guys caught smoking pot. One guy was in there for cheating on his wife with a 12-year-old girl. But most of it was very minor.”

Funk shared that he received more than 1,000 letters from supporters around the world and that military personnel did not mistreat him. During his initial incarceration, a prison official said he would be safer in solitary confinement because of his sexual orientation, but Funk declined and insisted on remaining with the general population.

Tedium and the rigors of military living, not hostile inmates, counted as Funk’s greatest enemies during his time in the brig.

During a visit to Camp Lejuene last November, Funk did indeed appear to be at ease within the brig, joking and looking relaxed during a three-hour visit with his mother, a reporter, and other visitors from New York. Funk talked about how other Marines did not support the war in Iraq.

Funk has always maintained that he does not consider himself a war hero, nor a champion of the war resistance movement. Rather, he has said, he was an aspiring college student who made a thoughtless decision and sought to separate from the military without causing grief.

“My job was never to go to Iraq,” Funk said. “That has been misreported. I was trained to maintain helicopter landing zones. Other guys were going to Iraq.”

Funk, whose family has supported him since he came out, has also stated that he has no desire to be a poster boy for the gay community.

“Whether or not I agree with Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell, the focus was the war in Iraq,” said Funk of his decision to oppose serving.

Funk spoke of the racism he faced in the military, noting that because he is of Filipino descent, he was singled out as the “laundry recruit” in boot camp.

“In the beginning at Camp Lejeune, I was told by guards that the others hated me, but that wasn’t true. People there were great and I became an ambassador of the anti-war movement,” said Funk. He attributed his prison sentence in part to what he described as a culture of denial and obedience in the military. “In the military you can get away with anything if you go with the program,” Funk said. He joked about how in the brig “the more independent thinkers threw things at the TV when Bush was on the news.”

The International Action Center office is part of a nationwide network established in 1993 by former U.S. Attorney General Ramsey Clark that combats racism, labor abuses, and militarism. Attendees at the Funk event were unanimously opposed to the war in Iraq.

One woman asked Funk if during his brig stay he was “able to make progress in showing that Iraq should be left to determine its own destiny?”

Funk replied, “I was an example of the military retaliating when you speak out. I knew my rights and it was clear what I had to do.” At another juncture, Funk added that he had spoken to service members who had served in Iraq. “The people coming back tended to agree with me—that it was about oil and we just needed to get out.”

Imani Henry, a queer activist who works at the International Action Center, helped organize visits to Funk at Camp Lejeune and attempted to gain him an early release. “Based on his courage and his leadership, he has helped the anti-war movement. Just look at the coalition of people he has brought together in his cause—Filipinos, Quakers, queer activists.”

Funk said he was grateful to the peace community for their advocacy on his behalf. “Without their help, I could have been in there twice as long,” he said.

Funk has embarked on a speaking tour to help organize against the war in Iraq. He also intends to apply to colleges around San Francisco where he now lives.