Christine Quinn waves to supporters as she concedes defeat in her run for mayor. | DONNA ACETO

BY PAUL SCHINDLER | In a sharp rebuke to her eight years as City Council speaker, Christine Quinn finished a distant third in the September 10 Democratic mayoral primary. Fueled by anger over her close ties to Mayor Michael Bloomberg, her role in giving him the chance to run for a third term, and –– in the Council district she has served since 1999 –– controversial land use development decisions many blamed her for, she garnered just 15 percent of the vote.

Perhaps most stunningly, as the city first viable out LGBT mayoral candidate, Quinn earned just 34 percent of the queer vote, according to Edison Research exit polls. Public Advocate Bill de Blasio, whose unofficial vote tally at 40 percent could free him from facing second-place finisher Bill Thompson, the former city comptroller, in a runoff, earned 47 percent of the lesbian, gay, and bisexual vote.

In her own geographic base, de Blasio bested the speaker by a 42-39 percent margin in Chelsea and a 50-34 margin in the West Village. In Brooklyn’s Park Slope, where de Blasio lives and the gay community has long been a visible presence, the public advocate romped over Quinn by a nearly three to one margin.

Appearing before supporters at the Dream Hotel in Chelsea after the September 10 results were in, Quinn, who for much of the campaign was viewed as the clear frontrunner, sounded an upbeat tone even as her eyes were moist with tears.

“We all care deeply about this city,” the speaker said of the Democratic primary field. “We share the goal of greater opportunity for every New Yorker in every neighborhood.”

Surrounded on stage by her large extended family, including her wife Kim Catullo, her father Lawrence, her sister Ellen, and her father-in-law Anthony, Quinn said, “I’m more grateful than I can say to my wife Kim. She is by far –– every day and twice on Sunday –– the best thing that ever happened to me.”

Noting the historic significance that a victory would have had, the speaker talked about “a young girl out there” who could say, “I can do that,” and the lifeline it would have sent to “a young LGBT teen out there who’s doubting themself for who they are.”

At the conclusion of her remarks, Quinn wipes away a tear. | DONNA ACETO

Vowing to stay engaged in public life after she leaves the City Council on January 1, Quinn closed by saying, “I believe that the best days of this city are ahead of us.”

The crowd gathered at the Dream Hotel offered a variety of reactions ranging from anger to shock to pride.

“She is about the classiest public servant I’ve ever worked with,” said Chuck Wolfe, president of the Victory Fund, which works to elect out LGBT public officials. “Like she said, she’ll keep working. For her, you can see that public service is a calling. We will never waver in our support of her.”

Nathan Schaefer, executive director of the Empire State Pride Agenda, New York’s LGBT lobby, said, “ We stood with Speaker Quinn as she rose from advocacy leader to elected official and through a highly competitive primary election season this year. Our early endorsement back in January shows our commitment to her strong record of delivering on issues near and dear to LGBT New Yorkers.”

He added that the group will “see what next steps she pursues, which we're certain will be of significance and with the best interests of our community and of all New Yorkers top of mind.”

The comments from others were considerably more raw.

Robert Pinter, whose 2008 false arrest on prostitution charges thrust him into activism over police treatment of the LGBT community, said he was “overwhelmed, shocked… and sort of speechless.”

“Even as far back as my arrest in 2008, there was organized opposition to her,” he said of Quinn critics who eventually came together under the slogan Anybody But Quinn and spent more than a million dollars in independent expenditure advertising against her. “I haven’t seen anything like it –– a campaign just to bring someone down. It did nothing to add to our political discourse.”

That effort highlighted a broad range of issues, from the speaker’s positive relationship with the mayor and her actions on the third term question to a scandal during her first term as speaker over a slush fund controlled out of her office, development controversies, such as the closing of St. Vincent’s Hospital and the site’s conversion into luxury condominiums, and even her support for the horse-drawn carriage industry.

“There were people who really, really, despised Chris,” Pinter said, “and what they said reached a lot of people.”

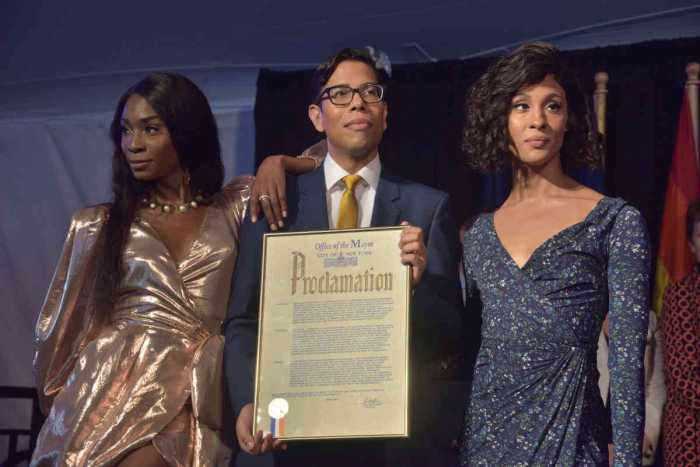

Quinn and her wife, Kim Catullo, arrive to meet her supporters. | DONNA ACETO

West Village Assemblywoman Deborah Glick, first elected in 1990, was more scathing in her assessment of the opposition Quinn faced.

“There was a lot of misogyny coming out of the Anybody But Quinn movement,” she argued, adding that comments made by de Blasio’s wife, Chirlane McCray, to New York Times columnist Maureen Dowd –– which were originally misquoted and published without their full context –– were “definitely code language… saying that a tough woman can’t be sensitive to the needs of other women.”

Glick added, “I don’t know if it was crafted by the campaign or if it was [McCray]. I don’t know the woman.”

Women and the LGBT community voted against their interests, Glick argued.

“Women don’t support women to the extent they should,” she said. “And I don’t know that the LGBT community is always strategic in their thinking.”

Rachel Lavine, a longtime activist in the LGBT community and the Democratic Party, echoed Glick’s assessment, terming Quinn’s loss “heartbreaking.” She described the independent expenditure committee that funded attacks on the speaker as “mysterious” and noted that none of the men in the race faced such opposition spending.

Lavine also faulted women and LGBT New Yorkers –– including actresses Cynthia Nixon and Susan Sarandon as well as McCray herself, who as a young woman identified as lesbian –– who allowed themselves to be used by the de Blasio campaign to make the argument “that her being gay isn’t enough, is it?”

“The fact that gay people did it does not make it any less homophobic,” Lavine said.

Stuart Appelbaum, the president of the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union who was Quinn’s most prominent LGBT labor supporter, said, “I obviously would have liked to have seen a different result,” but was already looking forward to the general election in November.

“Any of the Democratic candidates would be better than the incumbent because we need to focus on the people who have been excluded from his priorities,” he said.

Quinn’s loss to de Blasio among LGBT voters, he said, “was a move beyond identity politics” that “shows how far we’ve come.”

Still, imagining the impact a Quinn victory would have had on young gay New Yorkers, Appelbaum said, “I do think it’s a lost opportunity.”