Robert Talmas and Joseph Vitale with their son, Cooper. | COURTESY: JOSEPH VITALE

The routes two Manhattan gay men took to their seat in the Supreme Court chambers on April 28 listening to the historic marriage equality arguments could not have been more different.

Evan Wolfson first embraced the fight for gay marriage back in the early 1980s, when he wrote a Harvard Law School dissertation that, he explained this week, “mapp[ed] out the legal roadmap and cultural engagement” necessary to effect a profound shift in the way the nation and its courts view gay and lesbian people.

For the past dozen years, Wolfson has run Freedom to Marry, a perch from which he is widely acknowledged as the chief architect of the marriage movement. He earlier was a staff attorney at Lambda Legal, where he participated in the earliest promising marriage litigation, in Hawaii in the early 1990s.

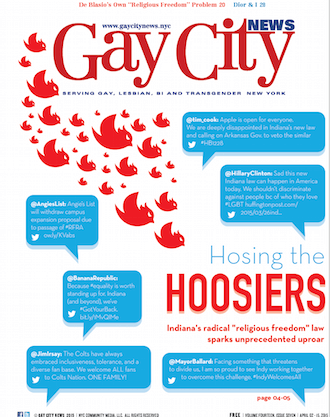

Joseph Vitale is a marriage equality battle newbie. In January 2014, Vitale and his husband, Robert Talmas, learned that the State of Ohio would not issue a birth certificate naming them as legal parents of their son Cooper, whom they had adopted at birth the year before in Cincinnati. The two men were married in New York and the adoption also took place here, with the court issuing a directive that a birth certificate naming both of them be produced.

Freedom to Marry's Evan Wolfson in Washington on April 28. | DONNA ACETO

Locked in a battle against gay marriage advocates, Republican Governor John Kasich and Attorney General Mike DeWine had earlier overturned longstanding State Department of Health policy that would have given Vitale and Talmas the birth certificate they sought for Cooper. When the two men learned Ohio was resisting the directive they won in their New York adoption proceedings, they quickly joined a lawsuit already in the works challenging the state’s marriage policy.

Last April, they prevailed in federal district court, but that victory was overturned by the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals in November. Vitale and Talmas’ case was among a group from Michigan, Tennessee, and Kentucky, as well, before the nation’s highest court this week.

“It was electrifying,” Vitale said of sitting through the Supreme Court hearing. “You imagine this and imagine that. It’s 50 to 60 times that. It’s an out of body experience. It’s very, very weird.”

Vitale and Talmas attended courtroom arguments at earlier stages in the litigation, so the issues knocked around at the high court were not new to them. Still, when asked if there were emotional high points in the day, Vitale responded, “The entire thing was. Everything struck a chord.” He did single out one moment, however, involving a clear ally on the bench: “It was very emotional to hear Justice [Ruth Bader] Ginsburg speak.”

The connection between the bigger issue and the personal was a profound one for Vitale. “They’re talking about your life,” he said in wonderment. “They’re talking about adoption, about your kid.”

A rally for marriage equality in Times Square the evening before the Supreme Court arguments. | DONNA ACETO

For Freedom to Marry’s Wolfson, Tuesday’s showdown at the Supreme Court represented a culmination of a much longer road, and after sitting through nearly two-and-a-half hours of argument, he was upbeat.

“I am very, very hopeful,” he said. After having made a “compelling case” to the nation over many years, most recently in the lower federal courts, and in written briefs for the high court, Wolfson said, the attorneys representing the same-sex couple petitioners were able to show the “real impact on people’s lives” that contrasted favorably with the “thinness and theoretical nature and implausibility” of the arguments from the other side.

Wolfson voiced no concern about the fact that Justice Anthony M. Kennedy, widely viewed as the critical swing vote, offered no clear signal about his intentions and even mentioned that a man-woman definition of marriage has prevailed for “millennia.” The “powerful moments that really connected” for the justices, Wolfson said — presumably with Kennedy in mind — “were on our side.”

Gabriel Blau (center), executive director of the Family Equality Council, with his husband Dylan Stein, their son, and Blau’s stepfather George Hermann, and his mother RoseAnn Rosenfeld Hermann, at a Times Square rally on the eve of the Supreme Court arguments. | DONNA ACETO

Wolfson has always declined to identify any one pivotal moment in the fight for marriage equality. The 2003 high court decision striking down sodomy laws was a crucial juncture in acknowledging the dignity of gay and lesbian lives, but even without that he believes the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court would have struck the first unambiguous blow for marriage equality later that year. The 2013 Windsor decision, which gutted the Defense of Marriage Act, was cited over and over again in dozens of marriage rulings since then, but for Wolfson that too was but one important milestone.

For Wolfson, the most profound words to have come out of any marriage equality ruling were written by Federal District Court Judge Robert Shelby in his December 2013 Utah decision.

“It is not the Constitution that has changed, but the knowledge of what it means to be gay or lesbian,” Shelby wrote.

“That encapsulated our strategy,” Wolfson said of a battle that stretches back even before his own engagement. “Windsor did not make that happen; it embodied it.”

The Supreme Court on the morning of April 28. | DONNA ACETO