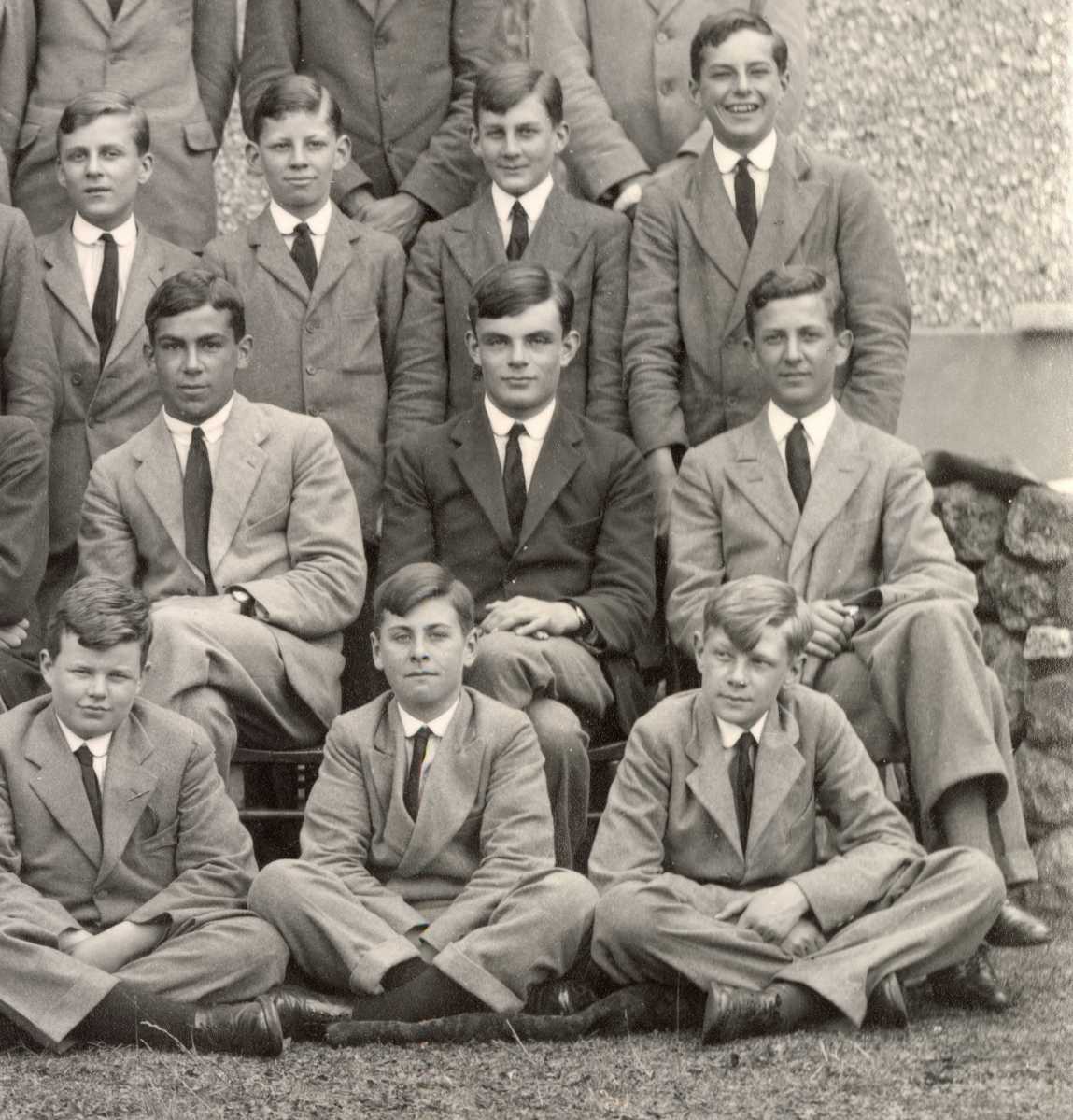

When British mathematician, computer scientist, philosopher, and theoretical biologist Alan Turing died in 1954 at age 41, it was in obscurity despite the fact that he was the father of modern computing and played the key role in breaking the Nazi Enigma code (dramatized in “The Imitation Game” starring Benedict Cumberbatch), shortening World War II substantially and saving millions of Allied lives. Under the Official Secrets Act, neither he nor his colleagues at Bletchley Park could speak publicly about their wartime work building their “bombe,” the computer that decrypted Nazi messages, even after the war.

Turing also died in disgrace, persecuted under the British laws against “gross indecency” for having a sexual relationship with another man — the same law that was used to sentence Oscar Wilde to two years hard labor in prison. Wilde died three years later at 45. In 1951, Turing was given a choice between prison and hormone injections meant to crush his libido, and he chose the latter and was never quite the same.

A total of three people attended his funeral — his mother, brother, and a friend, Lyn Newman, from his Bletchley Park days. When his wartime contributions came to light, he was voted the most admired British person of the 20th century and his image was placed on the £50 bank note. He was also granted a royal pardon from Queen Elizabeth II for his “crime” of homosexuality.

Rosemarie Reed’s affecting documentary “Forgetting the Many: The Royal Pardon of Alan Turing,” narrated by out actor Ben Whishaw and premiering at Cinema Village at 22 E. 12th St. on Dec. 6 and running through Dec. 12, illuminates this sorry episode in history but goes much further. There were an estimated 100,000 gay and bisexual men prosecuted under British anti-gay laws, which carried the death penalty until 1861. Some private same-sex behavior was decriminalized in 1967, but not for those in the military nor for people who engaged in sex with more than one partner at a time. And Reed’s film is most affecting when she lets these men tell their stories about how their convictions ended their careers and ruined their lives.

Steve Close, a soldier who was sent to prison for just kissing another man in 1983, spent 30 years barred from working in many meaningful professions. It took until 2013 for him to get his conviction legally “disregarded” — wiped from his record — and try to start life anew. We hear from former Labour Prime Minister Gordon Brown reading his government’s official apology for these anti-gay persecutions — though not all who have applied for pardons have been accommodated. If the act under which you were convicted is still a crime — such as sex in a lavatory — you are not eligible. And we hear from such men here.

The film includes interviews with scholars, journalists, and gay activists such as Peter Tatchell as they guide us through the long history of anti-gay laws in Britain. It covers from the time of Henry VIII, who screwed who he wanted to, married six times, and executed two of his wives. Touchingly, it features Turing’s niece and grandniece, who not only stand up for their uncle but for “the many” persecuted under these laws — including the endearing George Montague, who was pushing 100 at the time of his interview.

Without an autopsy or thorough investigation, the indifferent police quickly concluded that Turing took his own life in 1954. It fits with the standard martyr narrative embraced by many including in our community — that a gay man was hounded to his death. Reed’s film talks with those who question this version and suggest that Turing was not despondent — that his death may have been an accident due to careless use of chemicals in his home.

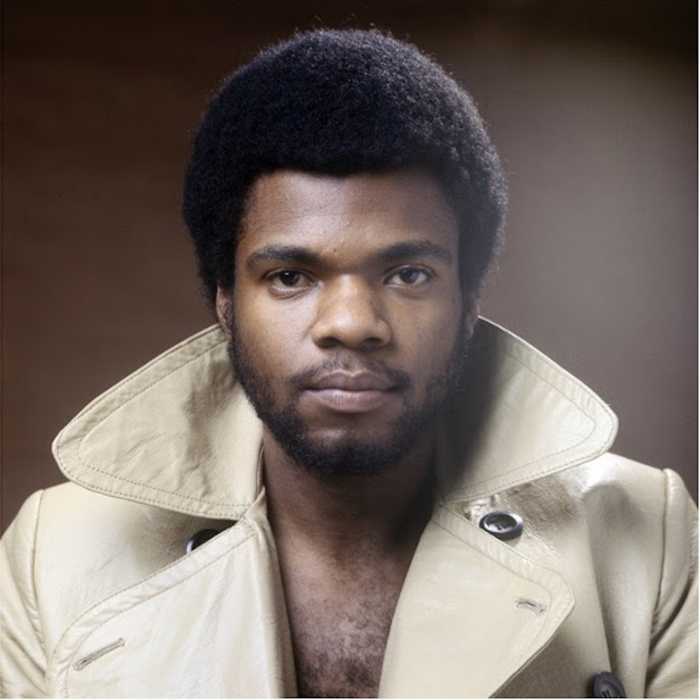

Reed also covers the spread of Britain’s anti-gay laws throughout its colonies — many of which have made those laws even more draconian, often under the influence of US evangelicals. Some of her subjects are from Nigeria, where we’re now seeing a wave of beatings of gay people by citizens taking the law into their own hands.

It’s a shameful history, though a few amends are being made. In Britain, compensation of £12,500 is being offered to some of the victims of the anti-gay persecutions — a token payment that men like Steve Close say hardly makes up for a life of misery and exclusion. There is no such push for any compensation for US servicemembers who were dishonorably discharged for homosexuality — no less for the countless civilians arrested under our anti-sodomy laws — though veterans’ benefits are being restored for some who served.

This film is a wake-up call to those who think anti-gay witch hunts are a thing of the past — at least in the developed world. Anti-gay laws in the UK ensnared tens of thousands, intimidated countless more, and — as we learn here — the effects of such persecution do not end after you’ve served your sentence.

“Forgetting The Many: The Royal Pardon of Alan Turing” is at Cinema Village at 22 E. 12th St. from Dec. 6-12. At the premiere on Dec. 6 at 7 PM, Andy Humm will moderate a post-screening panel including director Reed; Tatchell; David Bonny, who served 6 months in prison for being gay; Turing’s great niece Rachel Barnes; and Bisi Alimi, a gay Nigerian asylum seeker. All are in the film.