Like most goyishe New Yorkers, I have picked up a smattering of Yiddish over the years but only that. Still, I have always been impressed by and excited to see the work of the National Yiddish Theater Folksbeine (“The People’s Theater”), notably more recent productions like “The Golden Land” and Theodore Bikel’s piece about Sholom Aleichem. The company has been around for more than a century, and the recent productions have been notable for their directness, authenticity, social consciousness, and simple yet powerful theatricality.

The new production of “Fiddler on the Roof” is all of that and more. The show is performed in Yiddish, with English and Russian projected translations, but the show is probably so familiar to many that the titles are more a reminder than a necessity. Shraga Friedman who created the Yiddish libretto and lyrics has stayed close to the rhythms and the cadence of the original, so with very few exceptions the scansion is dead on. Thus, “If I were a rich man…” becomes “If I were a Rothschild…” Yiddish is, of course, the language that the residents of Anatevke, the fictional shtetl where the play is set, would have spoken. For a non-Yiddish-speaker, hearing the language focuses one on the action and the emotions of the characters in a powerful way.

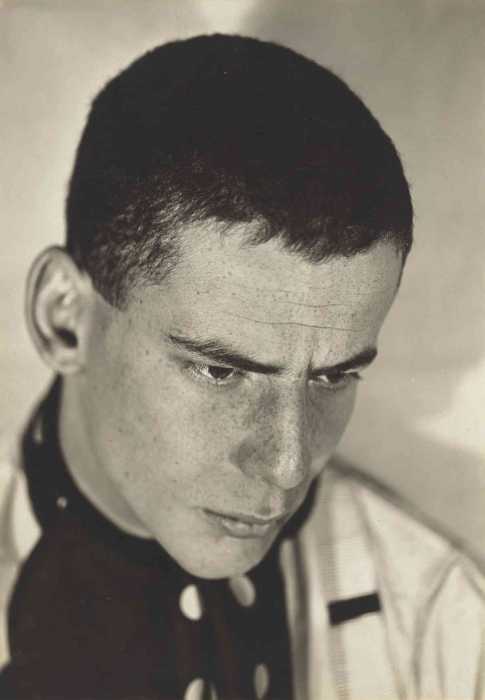

Under the direction of Joel Grey, the production is scaled down in its staging. There are no fancy sets, a few props, and it is performed on a largely bare stage hung with paper and cloth with a large, Hebrew word meaning “Torah” printed on one piece and looming over all the action. (I had to ask for the translation.) The direct, uncluttered staging, however, also enhances the emotional impact of the piece. With the shocking growth — or more public awareness — of anti-Semitism and issues of immigration and asylum in the public conversation, the story of an entire town given three days to leave or face violence is chilling. Although “Fiddler” is set around 1905, this kind of tragedy is still happening, as people are forced to lose their lives, their homes, and their traditions.

Traditions and our relationship to them are the overarching themes of “Fiddler,” particularly how these traditions are challenged by change. For the residents of Anatevke, traditions define all of life. In a world of poverty, they give life meaning and structure. They are to be protected, almost at all costs. Yet the central conflict of the piece is how Tevye, a simple dairyman who takes care of his family and has an ongoing conversation with God, can manage to keep his faith as the world changes around him and the traditions he’s depended on for his identity shift. That is, of course, the essence of the titular image: a fiddler continuing to play while balanced on a precarious surface.

Grey’s staging brings the full force of this tenuous equilibrium to the forefront of the production. Tevye engages in a Talmudic argument as he tries to balance new information with tradition, saying “on the one hand, but on the other hand.” It is through this that he realizes his daughter Tsaytl can marry for love and that his daughter Hodl will marry for love whether he give his permission or not. It is only when his daughter Khave marries outside the faith that he cannot accept the change — here is where he struggles, even after saying Khave is dead.

Change, however, is not all dire. As Tevye sees the happiness of his daughters in love, he turns to his wife of 25 years, Golde, and asks if she loves him. In a moving number, they realize that they love each other in their own way from their own time when marriages were arranged and they had to find their way from there. Though it changes nothing in their relationship, they say, it’s nice to know they’re loved.

Having seen many productions of “Fiddler” over the years, this one stands out for its emotional depth. There is a moment at the end of the first act, which I won’t spoil for you, that required virtually no stagecraft but is theatrically compelling, eliciting a gasp from the audience for what it represented.

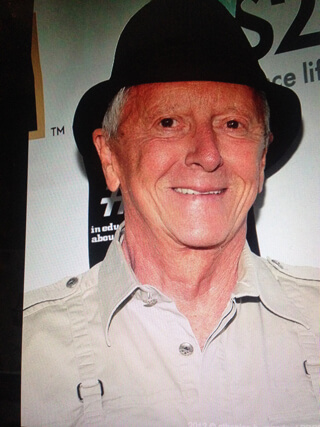

The cast does a superb job. Steven Skybell ranks with the best Tevye’s, though his performance is less showy and more organic than is often seen. It is a Tevye for our time as we all wrestle with a changing and frightening world. Jennifer Babiak as Golde is a perfect match for him. She is a powerful woman in an essentially subservient role as a wife, and how she achieves that balance is beautiful to watch. The three daughters — Rachel Zatcoff as Tsaytl, Stephanie Lynne Mason as Hodl, and Rose Jo Neddy as Khave — are narrative devices, each representing aspects of changing womanhood in the new world — from compliant to, if need be, defiant. All three actors elevate the roles beyond mere devices with rich internal lives and compelling performances.

Drew Seigla is an excellent Perchik, the student determined to create dramatic change in the world, deftly underscoring the political elements of the piece. Ben Liebert is outstanding as Modl, the tailor who finds his backbone because of his love for Tsaytl. Jackie Hoffman is sensational as Yente. The part is often played more broadly for laughs, and Hoffman can certainly do that, but her Yente has heart and vulnerability as well. When she says she’s going to make it to the Holy Land, it is a powerful statement of will, survival, and faith.

The songs are well known. After all, this is easily one of the most famous musicals of all time. For the most part, the production uses Jerome Robbins’ original choreography, and the familiarity of that works in its favor, even scaled down to accommodate the comparative intimacy of the production as a whole. This is a “Fiddler” that we know, but also one that engages our hearts and intellect in a bold, new way. It is a spellbinding balancing act.

FIDDLER ON THE ROOF IN YIDDISH | Stage 42, 422 W. 42nd St. | Extended through Sep. 1: Wed.-Thu. at 7 p.m.; Fri.-Sat. at 8 p.m.; Sun. at 6 p.m.; Thu., Sun. at 1 p.m.; Sat. at 2 p.m. | $69-$169 at telecharge.com or 212-239-6200 | Three hrs., with intermission