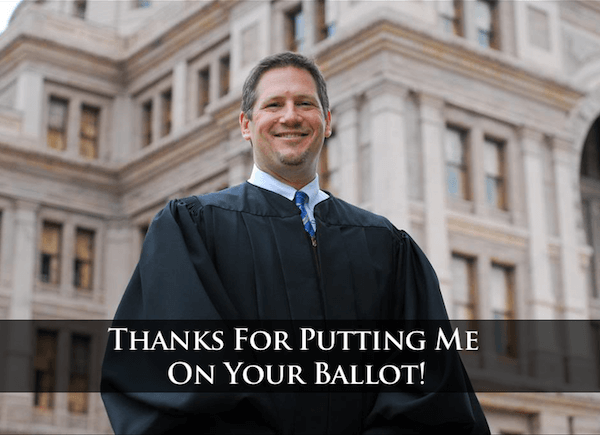

State Senator Jim Dabakis, Utah's Democratic Party chair, and partner Stephen Justesen were among 35 couples married by Salt Lake City Democratic Mayor Ralph Becker on December 20. | TWITTER.COM

A federal district judge has ruled that Utah’s ban on same-sex couples marrying violates a fundamental right guaranteed to them under the 14th Amendment. In a December 20 ruling, Judge Robert J. Shelby, appointed to the federal bench last year by President Barack Obama, found that the state had shown no rational reason for its statutory and constitutional ban on marriage equality.

Shelby did not stay his ruling pending appeal by the state, so couples were free to seek licenses immediately, and since Utah has no waiting period for marrying once a license is issued, gay and lesbian couples had wed before the day was over. The attorney general’s office, by that time, had filed a notice of appeal on behalf of Republican Governor Gary R. Herbert seeking to have the decision overturned by the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals. It is unclear whether a stay of Shelby's order might yet be granted to the state.

On December 23, he denied a motion by the state to stay his ruling and the state filed an “emergency” motion with the 10th Circuit — its third effort to get the appeals court involved — seeking a stay pending its appeal. Meanwhile, hundreds of same-sex marriages were performed throughout the day in Utah, although a handful of county clerks kept their offices closed in a refusal to issue such licenses. The 10th Circuit directed the marriage plaintiffs to file a response to the state’s motion by 5 p.m. Mountain time that day, but as Gay City News went to press a short time later no further information on the status of the motion was available.

Among the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals’ 10 judges, three are Obama appointees, with four from George W. Bush, two from Bill Clinton, and one from George H.W. Bush.

Within hours of December 20 ruling, licenses issued, couples marry

Two Utah lawyers unaffiliated with LGBT legal advocacy groups, Peggy Tomsic and James E. Magleby, filed suit on behalf of three same-sex couples. Two of the couples had been denied marriage licenses by county clerks, while the third was married in Iowa and is seeking recognition of their marriage by Utah. The case moved quickly to summary judgment, the motions having been argued just weeks ago.

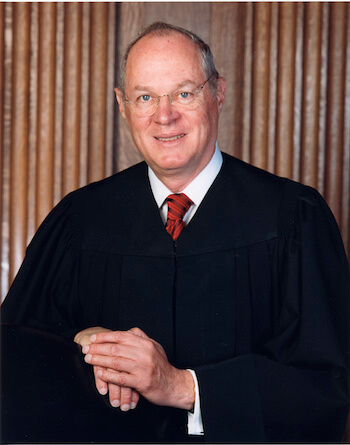

Shelby’s opinion is the first federal court ruling since the Supreme Court’s June DOMA decision to find that same-sex couples have a federal constitutional right to marry, guaranteed by the due process and equal protection clauses of the 14th Amendment. Noting that the Supreme Court, in 1972, declined to hear a gay marriage case, stating it did not present “a substantial federal question,” Shelby concluded that many high court cases decided since then, culminating in the DOMA ruling, have created a substantial federal question. And, in no small irony, he quoted Justice Antonin Scalia’s dissent in the DOMA case, that “the view that this Court will take of state prohibition of same-sex marriage is indicated beyond mistaking by today’s opinion. As I have said, the real rationale of today’s opinion is that DOMA is motivated by ‘bare desire to harm’ couples in same-sex marriages. How easy it is, indeed how inevitable, to reach the same conclusion with regard to state laws denying same-sex couples marital status.”

On this point, Shelby wrote, “The court agrees with Justice Scalia’s interpretation of [the DOMA ruling] and finds that the important federalism concerns at issue here are nevertheless insufficient to save a state-law prohibition that denies the Plaintiffs their rights to due process and equal protection under the law.”

Regarding the plaintiffs’ due process challenge, Shelby showed that the Supreme Court has consistently treated the right to marry as a fundamental right. The state, he said, made the absurd argument that gays are not deprived of this right because they can marry partners of the opposite sex.

“But this purported liberty is an illusion,” the judge wrote. “The right to marry is not simply the right to become a married person by signing a contract with someone of the opposite sex… A person’s choices about marriage implicate the heart of the right to liberty that is protected by the Fourteenth Amendment. The State’s argument disregards these numerous associated rights because the State focuses on the outward manifestations of the right to marry, and not the inner attributes of marriage that form the core justification for why the Constitution protects this fundamental right.”

The plaintiffs had shown, Shelby found, that the “right to marry” as framed by the state was, for them, “meaningless.”

He also rejected the argument that same-sex couples’ inability to procreate on their own disqualifies them since that “is not a defining characteristic of conjugal relationships from a legal and constitutional point of view.” That justification for marriage, he found,“demeans the dignity not just of same-sex couples, but of the many opposite-sex couples who are unable to reproduce or who choose not to have children.”

He also rejected the state’s argument that the plaintiffs were seeking some new right of “same-sex marriage,” as opposed to the well-established fundamental right to marry. “The alleged right to same-sex marriage that the State claims the Plaintiffs are seeking is simply the same right that is currently enjoyed by heterosexual individuals,” he wrote.

Shelby also rejected the idea that the right at issue could not be fundamental because it was not construed in the past to extend to same-sex couples. “The Constitution is not so rigid that it always mandates the same outcome even when its principles operate on a new set of facts that were previously unknown,” he said. “Here, it is not the Constitution that has changed, but the knowledge of what it means to be gay or lesbian. The court cannot ignore the fact that the Plaintiffs are able to develop a committed, intimate relationship with a person of the same sex but not with a person of the opposite sex. The court, and the State, must adapt to this changed understanding.”

Shelby also pointed to the majority opinion in the 2003 Texas sodomy case, where Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote that “our laws and tradition afford constitutional protection to personal decisions relating to marriage, procreation, contraception, family relationships, child rearing, and education” and held that “persons in a homosexual relationship may seek autonomy for these purposes, just as heterosexual persons do.” Scalia’s dissent there seized on this statement to complain that the decision opened the door to same-sex marriage, and again Shelby agreed.

Since Shelby viewed this as a case about a fundamental right, the burden on Utah was to prove a compelling interest in denying same-sex couples the right to marry. But the judge found that the state failed to articulate even rational, never mind compelling, reasons for excluding same-sex couples from marriage. In arguments strikingly similar to ones made the day before by New Mexico Supreme Court Justice Edward Chavez in its marriage equality ruling, Shelby found that some of the interests the state said it was protecting by banning same-sex marriage were actually harmed, especially regarding the raising of children –– those with same-sex parents.

In addressing the plaintiffs’ equal protection argument, Shelby was required by Tenth Circuit precedent to apply a rational basis test to claims of sexual orientation discrimination, according to which the state’s policy is presumed to be constitutional unless the challengers can show it is lacking in any rational justification. And that was precisely the conclusion Shelby reached in his due process analysis.

“The State was unable to articulate a specific connection between its prohibition of same-sex marriage and any of its stated legitimate interests,” Shelby wrote. “At most, the State asserted: ‘We just simply don’t know.’ This argument is not persuasive. The State’s position appears to be based on the assumption that the availability of same-sex marriage will somehow cause opposite-sex couples to forego marriage. But the State has not presented any evidence that heterosexual individuals will be any less inclined to enter into an opposite-sex marriage simply because their gay and lesbian fellow citizens are able to enter into a same-sex union. Similarly, the State has not shown any effect of the availability of same-sex marriage on the number of children raised by either opposite-sex or same-sex partners.”

Prior to the Utah decision, 17 states and the District of Columbia had formally legalized marriage equality. With Utah, more than 38 percent of Americans would live in jurisdictions where same-sex couples can marry.

Editor's note: This story was updated on December 22 to reflect action taken by the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals that day.