An HIV flick treads cautiously on dangerous ground

The scenario is the worst nightmare for some married men. A friendly drink with an attractive guy in a bar leads to an isolated incident of sex. Not long after, the married man’s wife is diagnosed with HIV. What to do next?

In the case of Tony Piccirillo’s “The 24th Day,” the answer is to get revenge, of a sort. Scott Speedman plays Tom, a short-order cook who, consumed by rage and sorrow over his HIV-positive diagnosis only 24 days prior, decides to find the man he believes infected him. That leads him back to Dan (James Marsden, of “X-Men” Cyclops fame), the attractive, martini-swilling, sweet talker he hooked up with five years earlier. It doesn’t take long before Tom lures Dan to his East Village rattrap for what is supposed to be a tryst.

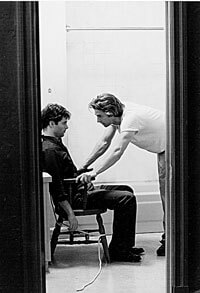

Slowly, it dawns on Dan that he has been there before and the encounter begins to seem pretty sketchy to him. Just as he’s about to hit the road, Tom knocks him unconsciousness. When he comes to, he’s tied up like a heifer at a gay rodeo and learns that Tom has drawn his blood and given it to a nurse friend for HIV testing. Tom delivers this ultimatum: If the test comes back negative, Dan lives; if it’s positive, he dies.

As the story progresses through the two or three days it takes Tom to get the test results, an interesting dynamic evolves. During the day, life goes on for Tom—he goes to work, hangs out with friends, watches the game, and has a few drinks. Back on Avenue A, however, it’s a battle, as Dan struggles to escape from his captor, using his strength and wits.

Tom’s past is revealed to the viewer through a series of jarring and somewhat heavy-handed flashbacks, in which we see his young wife, diagnosed five years prior with HIV, her death from a car accident as she leaves the hospital, Tom’s discovery of what his wife learned just before she died, and his resulting self-blame. He believes that his dalliance with gay sex is directly responsible for the death of the woman who was his high school sweetheart, though he does not seek revenge until confronted years later with the fact of his own infection.

Tom is intent on making Dan pay, but in the course of their time together, the two men begin to reveal themselves— in particular, we learn about Tom’s pain and confusion, his thwarted childhood dream of being an architect, his love of sports, his favorite Charlie’s Angel. But, as Tom reminds his hostage, “We’re not two pals sitting here watching the game, Dan.”

The two also tackle some more weighty issues, like the idea of safety, the meaning of truth and responsibility, and the concept of personal choice.

Dan, who insisted all along that he is HIV-negative, makes a persuasive argument that if Tom’s wife showed symptoms nearly five years before and he was only recently diagnosed, the likelihood is that she infected him, not vice-versa. Dan also points out that even if his test does come back positive, Tom will always wonder if it wasn’t his wife who passed it on to him in any event, if her own guilt might have led her to propel her car into a busy intersection.

The movie reaches its conclusion with more questions raised than answered, and with a stubborn resistance to find any simple happy ending to the dilemma facing the two men. Speedman and Marsden deliver powerhouse performances, and Piccirillo does a brilliant job of dealing not only with extremely sensitive issues, but also with the serious emotional weight that accompanies them.