The slow-burn drama “Drift” follows Jacqueline (Cynthia Erivo), a Liberian refugee, as she wanders the streets of a picturesque Greek island. She tries to keep a low profile and go unnoticed as she steals packs of sugar to eat or pilfers a bottle of olive oil to use to give foot massages to tourists on the beach to earn her money for food. (Jacqueline is also not above finishing off a cup of coffee left behind at an outdoor café or an abandoned meal — if she can get away with it.)

Homeless, she sleeps on a makeshift bed in a cave on the beach, hitching a ride on a resort hotel bus to get to and from town. Jacqueline also tries to hide from the other Africans on the island, who may get her into trouble. In addition, she avoids the police as much as possible, passing herself off as a journalist one night when she is stopped by a cop.

Through all these moments, Jacqueline’s face becomes a mask as she tries to hide her pain which goes beyond hunger, homelessness, and fear. “Drift” eventually reveals why Jacqueline is struggling to survive in “paradise,” even if it doesn’t explain how she got where she is.

Based on the novel “A Marker to Measure Drift,” by Alexander Maksik — who cowrote the screenplay with Susanne Farrell — director Anthony Chen has crafted a probing character study. The first act establishes Jacqueline’s unpleasant present situation, while flashing back briefly to happier times — first with her British girlfriend, Helen (Honor Byrne Swinton), in London, and second through memories of her family in Liberia. Jaqueline sports long braids in both flashbacks, as opposed to her shorn head of hair in Greece, which will help viewers keep track of the time periods. (A haircut symbolizes life change in literature, and as “Drift” shows, Jacqueline’s life definitely has some seismic changes.)

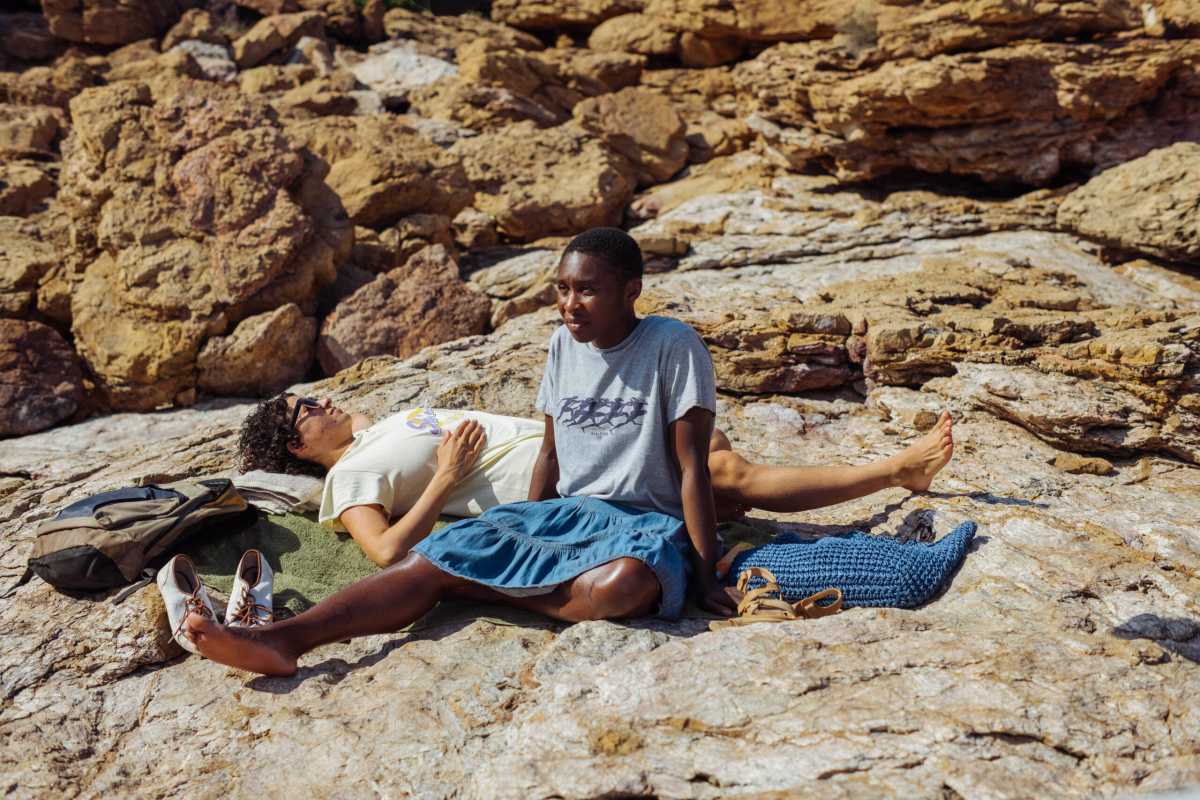

The second act has Jacqueline drifting into an unexpected friendship with Callie (Alia Shawkat), an American who now lives in Greece and works on the island as a tour guide. Callie is as outgoing as Jacqueline is shy and vulnerable. They meet when Jacqueline crashes one of Callie’s tours. The young women talk and laugh, and the film hits its stride with their easygoing friendship. Callie takes an interest in Jacqueline most likely because Callie longs for someone to talk to about something other than the history of Greek ruins and mythology.

Callie probably notices that Jacqueline never changes her clothes, and likely intuits that Jacqueline is lying about having a husband. Callie also might think it is strange that Jacqueline cannot remember the name of the hotel where she and her “husband” are staying. But Callie helps Jacqueline when she is caught rummaging through purses on the tour bus while looking for a tampon. Callie also accompanies Jacqueline to the hospital after her friend injures her head in a fall.

Callie’s support offers both lonely women different forms of comfort and connection. But there is an unspoken tension. This is not exactly sexual; neither woman comes out to the other. A dinner they share feels like a date, but it is Jacqueline’s effort to repay Callie for her unwavering kindness. It also feels like a missed opportunity for these two women to not couple up. However, each is still processing pasts traumas that have left them adrift. They are, as Callie says in one of the film’s more potent lines, “living out their failures.”

Callie orally recounts a painful episode from her life, but Chen shows the horrors that befell Jacqueline and her family — a disturbing episode. The film gets most of its emotional power from these trauma scenes because the rest of the film is so low-key.

Erivo gives a riveting performance as Jacqueline, even as she makes a series of bad decisions, albeit out of a need for self-preservation. Erivo makes these odd moments — such as putting on wet clothes pulled out of a washing machine in mid-cycle — believable because she performs them with such conviction. “Drift” does not seek to explain her character — until the trauma is revealed — as much as observe her as she drifts through time and space. When Jacqueline tries to reach Helen by phone one day, she is stunned to learn that three months have passed, not one. Her reaction to this news is telling and shows the strength of Erivo’s performance.

In support, Alia Shawkat is ingratiating as Callie. She is charming, dropping tidbits about her life as she hangs out with her new friend, but she also reacts in a way that is thoughtful and moving when she hears Jacqueline’s harrowing tale.

“Drift,” ultimately is about healing, and while the film may not be entirely convincing, it is frequently compelling.

“Drift” | Directed by Anthony Chen | Opening February 9 at the Quad Cinema | Distributed by Utopia Distribution.